Pzena’s Philosophy of Empowering and Profiting from the Uncertain

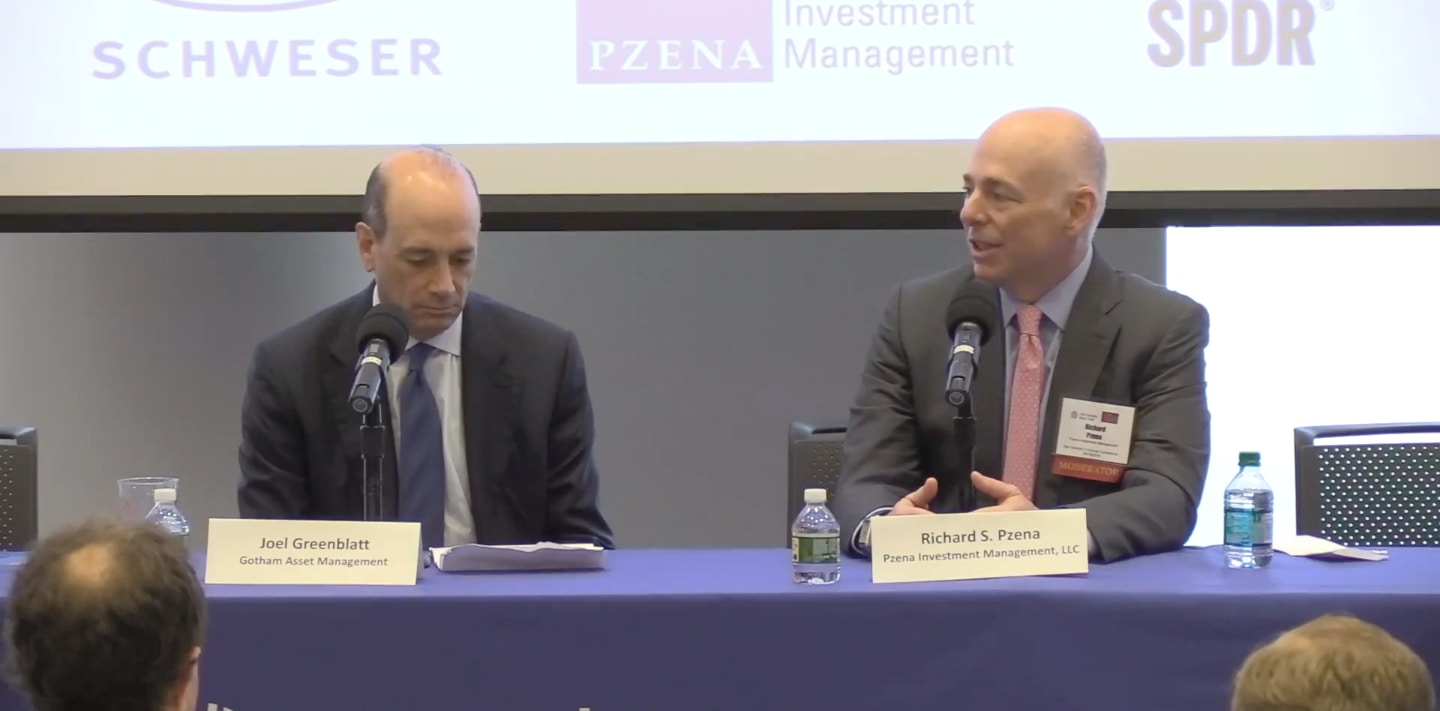

Founded by Richard Pzena around 1995, Pzena is known as an investment management firm that has expertise in managing value equities and assets.

Its investment philosophy could be described as ‘discount financials hunting’ – it seeks to make investments in good businesses at low prices and generate excess returns over the long term.

According to the Form ADV, it further develops this by focusing on comprehensive earnings forecasts and the resulting company value. The next step is to build portfolios of securities they consider undervalued, compared to their long-term earnings power.

About its people, the firm’s senior investment leaders are an active part of the research review process, including founder and Chief Investment Officer Richard Pzena, who believes the issue with value is not measurement but human nature.

Reported by Finbox, in 2020, the company reaches its peak revenue in the near five years at $138M with its previous successful implementation of the new technology to drive data strategy. While the firm is the business of investing other people’s money, let’s make sense of the company’s investing strategy and process!

Pzena’s Philosophy of Business on Sale and Deep Value Investing

Knowing investors cannot approach and notice the longer-term opportunities of businesses, the firm set a mission to use a deep-value approach to buy those at low present value. This is the transparent talk on Pzena’s investing strategy. How does it make money and the genesis that has thrive since 1995?

“The philosophy is old-fashioned value: Try to find good businesses when they go on sale,” says Pzena on an interview with Value Investing Insights. But how do you define what is value?

There is no magic or secrete about value investing, every investor would say their job is to buy good businesses at low prices, he says, that is the genesis of investing. But the problem is good business does not sell for a low price. So, what you should look at is what makes something cheap, a missing piece that need you to recognize and hone it, before anybody did. It’s about taking risks and tapping in the uncertain that dive most value.

The company’s founder claims, he is looking to buy when these five criteria are satisfied.

The Scientific of Screening for Buys

First, its price should be relatively low to the company’s ‘normal’ earnings. In this case, ‘normal’ is what should this business earn given a mixture of ingredients including its history, the industry structure in which it competes competitor margins, individual company strengths and shortcomings and its management. The criteria of price also introduce the first stage of the firm’s buying process – screening.

The screening process is proved a scientific practice, however, “our estimation of normal earnings is not a scientific number.” How does the firm screen for potential buys?

Pzena shares it’s essential to has the right technology in house – for instance, its recent partnership with Reformis to install the new data management solution. Which could help rank the firm’s value universe of the 1,000 largest domestic companies. It ranks all 1,000 companies from cheapest to most expensive, on the basis of current price to the normalized earnings in the five years period.

And from the computer screen, the firm look closely at companies’ financials and industry dynamics to do an initial review on the cheapest quintile of these stocks. “After this initial research, we reject about 75% of these companies. The other 25% we do detailed analysis on, including visiting the company and meeting management,” Pzena explains. And ended up buying roughly about 13% of the cheapest 200 stocks in its universe.

Bad Performance Is a Good Sign for Buying?

Second, current earnings that are below normal are also diagnosed. The firm claims it would buy companies whose margins have fallen below their historic norms. “That’s important to us – we avoid companies that are doing better than usual, which makes us really skeptical,” Pzena insists.

While performances below historic norms are somehow not bad news, does it matter to ask ‘why’? Obviously, according to Pzena the right question should be whether you can convince yourself that the situation is temporary and can reverse itself – with specific data and evidence, of course.

“I’ll invest if I believe the situation is not permanent.”

Seeking out businesses that are at low valuation or under-earning, the firm expects to win in these two specific ways. One – is improved valuation; two – is an earning-rebound, growth rates that can be enormous as you are coming off a depressed level to a more normal level, Pzena explains.

Listen to the Breath of ‘Basically Everything’

The third thing Pzena considers is whether management’s plan to restore their business back to historic norms is a sensible plan, whether they can execute it. Upon this, try to gather information on the industry conditions and listen to what people are saying, listen to every breath of every department. Can they deliver what they are promising, does it make sense and what does the track record say?

But what if the competitive environment has changed? Companies are also entering the unknown themselves, how much can you tell if it would work? Of course, it’s not simple as it sounds to determine if the plan is going to work, therefore, you have to consider the case where the plan fails. As Pzena puts it “Value is created when you don’t know what is going to happen.”

Which leads to the fourth and fifth criteria!

Definition of a Good Business

The fourth is to ask whether the business is a good business. According to the founder, a good business is defined if you can precisely name reasons why it should be able to earn a return in excess of its costs of capital.

That could come in many forms: a franchise brand, a competitive cost position, an installed base of business, unique technology – some reason to believe that even if the current management fails to restore earnings, somebody else would want to try like an acquirer of the assets.

The fifth and also the last one, is that you need a downside protection because nobody want to lose a lot of money especially when they were wrong. There are two forms you could recognize your protections: one – in the established revenue franchise of the business, two – in the company’s physical assets.

“For example, if you were going to look at Whirlpool, the physical assets of the company are probably not worth a lot. What is worth a lot is the Whirlpool brand,” the founder cites. Therefore, even at worst scenario when management team wreck the business, somebody else would want to buy the valuable piece of property of the brand. In that case, when you were wrong on earning expectations, you would not get killed.

At the company, he says, the metrics generally are that it can envision losses of no more than 25% in any of the companies it owns. “And we expect upside significantly above that, giving us a more favorable risk and reward outcome.”

The fifth criteria also introduce to the final stage of the firm’s research process. At this point, Pzena and the team will invite a Wall Street analyst who is a ‘bear’, and they come in and make a pitch why your firm should not buy this stock. You need to see if they have different perspectives, or a real structural flaw in the business that you did not pick up on, your blind spot.

Most of the time bears could be negative just because of “no earnings visibility,” however, to Pzena this is just the Wall Street language for “I don’t really have a clue what is going to happen next.” And that is where investing managers like the firms see through thick veils and make profits out of that.

Overall, Pzena understands that it could be unrealistic sometime to expect such opportunities to be available without some problems which cause the share price to drop. However, the question the founder and his team try to answer is whether the issue that caused the fall is temporary or permanent. It’s a typical scenario to see companies’ earnings and business chugging along and then get hit with problems. And the firm wants to seize that opportunity to make great business out of it, not only for investor but also the business itself. You can barely tell if a downturn is cyclical or secular in nature, but you should be able to.

Discipline on Selling Decision

While buying takes many steps and space, it does not that complicated with selling. When a stock reaches the midpoint of the ranking the firm had discussed, from cheapest to most expensive, Pzena says, the team would sell automatically.

The good outcome is you buy, the stock price goes up and gets more and more expensive relative to its normal earnings, so it falls in our ranking. As a stock price goes up and becomes less cheap, you would want to hold less and trim it back as it’s going up and bounce out when it reaches the midpoint.

How did they come up with that discipline?

“You know what? I arrived at that because otherwise I would have no idea how to sell.”

If you let your emotions dictate when to sell, you risk falling in love with companies that have been doing well and you ride them too long, and then something goes wrong. Therefore, discipline in selling is vital.

“I guess I have the classic value mentality. It’s instinctual for me to want to sell as things go up and I start getting nervous,” he insists, it’s important to have a system that can tell if something is cheap or just fairly valued.

Develop your own systematic discipline and stick to that. Don’t say that your goal is to pick stocks that will going up next because after that all you probably doing is to guess market sentiment, but instead try to think about what something worth and apply common sense to it. At least that was how he started earlier!

Last but not least, Pzena also shares his biggest lesson as a professional and entrepreneur. “Value investing and asset financials leverages are not good bit fellows.”

The biggest lesson value investing, and financials leverages are not good bit fellows. You do not want to mess with things that have the chances of going bankrupt. Because even though they could appear to be very cheap, and you gamble that they could be back to normal and make 10 times money. But the odds are you are fooling yourself.

Pzena’s Differentiator

At a time where people are overly sensitive to short-term result, it is not just the sell-side, it’s also the hedge fund community. Why the firm looking at earnings 5 years out rather than 2 to 3 years period like other investor or sell-side analysts doing with earnings revision?

It is even shorter than that, Pzena says, they are looking over a 1to 2 years period, or even less than 1 year. Anybody that runs business would know, especially one that only needs one bad year to destroy half of the business. You would be very focused on the short-term, even if you are a long-term kind of person, it is hard not to be. However, the founder says, it is better to run a business where you promise your clients you are going to have bad years, which is what you do.

If clients ever ask, “What about investing in value traps or investing in dead money,” promise them you are going to do that too. It’s does not mean you shouldn’t avoid it if you know which one is going to be a value trap in advance.

But how do you know in advance? “I think the attempt to avoid value traps is what keeps people from being real value investors,” he claims. It’s like a rule, for something to be real value, you cannot tell whether it’s a value trap or not. If it was labeled obviously that this one was a value trap and this one was not, they would not sell for the same price.

It’s essential for your clients to understand the nature of investing and how you are trying to deliver that value. You have to be willing to accept that some of your investment is going to be wrong. “This’s how I define value trap: you buy something, and your thesis is wrong. You thought it was value, but it was not.”

Sometimes there will be a research mistake. You make judgment based on probabilities, it turns out not to be what you expected, and you lose money.

But that ironically is what it takes to win: by not being afraid to lose. So long as you can understand how much you’re going to lose. If you think there’s some probability that the company is going to be wiped out, then that’s another story. But making the judgment that the margin structure for the hospital industry should be about 15%, you’re not going to be that far off, and even if you’re wrong and it turns out to be 11 or 12%, you’re not going to lose a whole lot of money.

The Bottom Lines

Prior to the firm, Richard Pzena himself has experienced as a Chief Investing Officer at Sanford C. Bernstein in New York. Decades into the business of investing, the mentality of deep value investing never cease into existence, but only develop over and over with increasing amount of successful evidence.