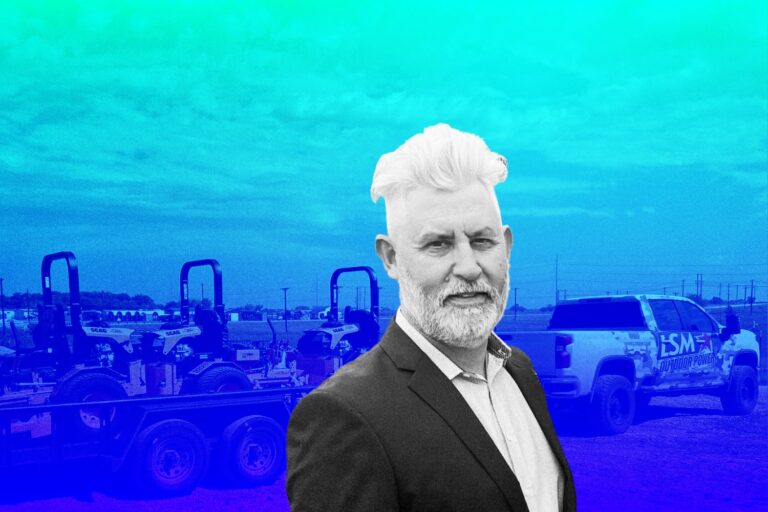

This Man Took a Seat at The Table in Almost Every New Tech Deal

Coming up with a ground-breaking concept is the start of an exciting journey, but it may also be the easiest. Taking that idea and projecting it onto the world stage tends to take industry expertise, a web of established contacts and enough fund to build the idea from seed funding to long-term growth.

That’s why entrepreneurs are not alone in the journey that drive the U.S. economy. At their side stands the venture capitalist, a trail-wise best friend ready to help the hero through every tight spot—in return, of course, for a piece of the action.

In that setting, one of the capitals that has been roaming the Silicon Valey for more than a decade could be named Andreessen Horowitz (known colloquially as a16z). This investment firm has their sight set squarely on the future and is passionate about bringing transformative ideas to the global market.

Behind every successful enterprise is an ardent vision of the captain, and in this case, Marc Andreessen just shines. He is the father of this big guy a16z that aims to aid the dominance of the internet since the inception of this capital firm. However, the journey to victory is much more fascinating than the trophy itself. This article will give you a breakdown of how this man got his chair in the severe VCs’ world.

From a Small Town Guy in New Lisbon to a VC Disruptor

Marc Andreessen was born on July 9, 1971, in Cedar Falls, Iowa, to his parents Lowell and Patricia Andreessen. In New Lisbon, Wisconsin, he was raised.

It is a long way from his small-town roots in New Lisbon, Wisconsin, when he recalls considering Chicago a “big cosmopolitan city, with all the fancy people”. His extended family farmed in Iowa. His mother, Patricia, was a stay-at-home housewife, while his father, Lowell, sold seed corn for an agricultural company.

He eagerly alludes to an essay by Tom Wolfe about Intel’s founder and Iowa country boy Robert Noyce. Wolfe connects the equality of the farm to Intel’s open mindset and cubicle culture. “When I finally read that, I was, ‘Oh!’”, said Marc Andreessen.

As a child, Andreessen was captivated by technology. “I have the complete series of Tom Swift from the 1910s to 1950s in my office. That was probably the single most important thing I read,” he shared, speaking of the science-fiction and adventure books featuring a teenaged inventor hero (Tom Swift and his Photo Telephone was one 1912 title). “I liked all the stuff he’s inventing.”

In his 20s, Marc Andreessen co-created Mosaic, the very first internet browser to be widely used. He soon relocated to Silicon Valley where he met an entrepreneur, Jim Clark. Together, this pair designed Netscape, which would become the most widely used web browser of the 90s.

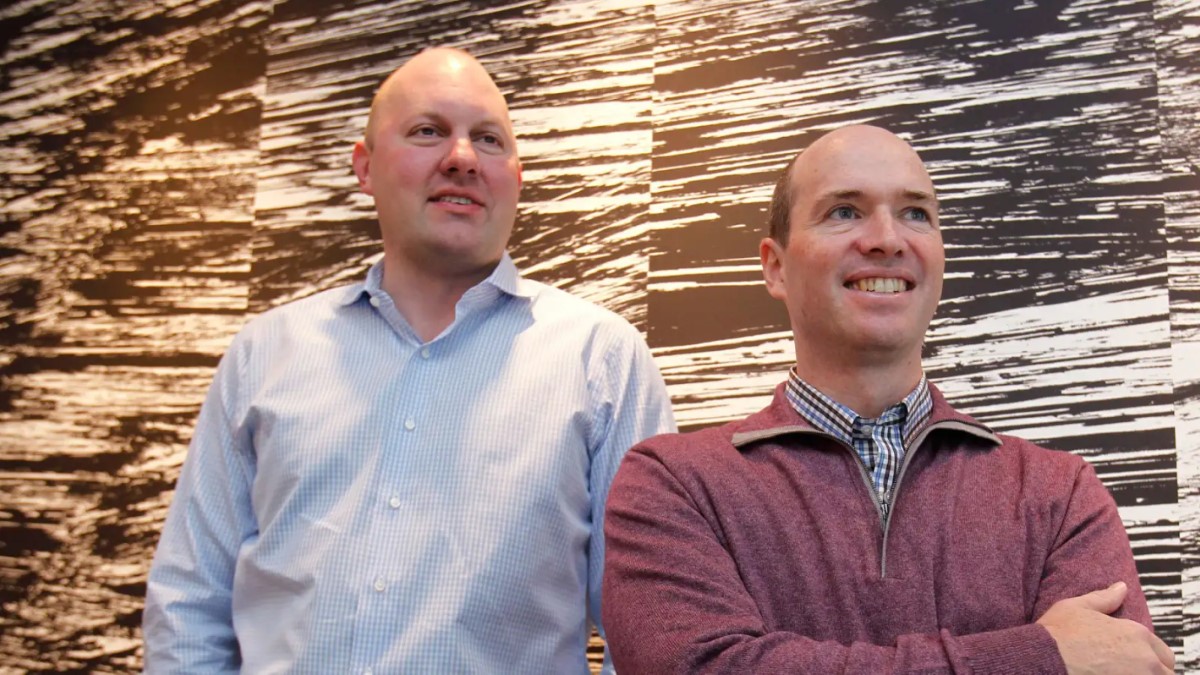

Ben Horowitz and Marc Andreessen first collaborated at Netscape. They then co-founded Loudcloud, a pioneer in the cloud computing industry, which HP acquired in 2007 for less than $2 billion.

The two discovered that they got along well over time. Andreessen, who is more interested by the digital future than Horowitz, is the more technical of the two. According to Andreessen, part of their victory together is due to Horowitz having essential traits that he lacks, like strong management skills and character judgment.

The two experimented with venture capital prior to co-founding a16z, developing a reputation as rebels in the process. They invested their own money in 36 firms in their first three years as rookie angel investors, about one per month. The largest check they ever signed during those years was for about $200,000.

Prior to actually launching their firm, they already had invested $10 million of their personal net worth into about 50 tech startups, among them Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

In July 2009, flush with $300 million of freshly raised capital, they officially opened the doors of their new investing firm, Andreessen Horowitz. Their plan was to reimagine Silicon Valley’s investing approach and combine it with their worldview of digital technology. “The world will soon be consumed by software”, according to Marc Andreessen.

There is an interesting fact that this company was serious about avoiding such prominent investment hotspots as infrastructure and transportation businesses as well as limiting its attention to software firms with extensive web applications.

Marc Andreessen and His Savvy Bet on the Dominance of Software

More than ten years ago, particularly on August 20, 2011, Marc Andreessen, influential investor and the co-founder of Andreessen Horowitz, published a vital story in the Wall Street Journal: Why Software is Eating the World (also reprinted on his venture capital firm’s Web site). This was as much a writing on the wall for many traditional businesses as it was fantastic news for the software industry.

Andreessen saw it coming early since he was an industry insider. No, more so as an entrepreneur than just a VC. This software engineer pioneered Netscape, the first of its kind web browser that went on to compete with the then-dominant Microsoft Corporation, at the height of the tech industry in the 1990s. He gained firsthand knowledge of the IT industry’s ins and outs as well as its nitty-gritty.

And Andreessen was right.

Today, many reports cite the increasing influence of software developers. And as we all know, currently almost every firm depends on software. The coders are in charge, and it’s truly the Revenge of the Nerds.

Today, because to some truly amazing technological advancements, you can sit at a keyboard, type letters and figures, hit Enter, and the world will instantly transform. “Right? The real world reorganizes itself according to what some coder has typed into a software.” Andreessen once said.

According to Andreessen, technology is facilitating the “big awakening.” Waggling his iPhone affectionately, he once stated, “This little guy right here is the equivalent power capability of the $20m supercomputer I was using. This thing is in two billion people’s hands.”

Andreessen is one such optimist. In fact, he considers him to be the “most optimistic person he knows.” It takes a great deal of conviction to even say that half-heartedly.

One of the firm’s most highly publicized beliefs is that it doesn’t matter how many of its investments screw up, only how many succeed massively. Out of the many agreements they close, as shared by this optimist guy, only 15 on average each year account for their enormous profits.

In just a little over a decade since its founding, Andreessen Horowitz has climbed the ranks of Silicon Valley’s most elite venture capital companies and made its investors billions of dollars in profits—possibly because of this mindset.

As a tech investor, optimism is embedded in his personality. It’s easy to understand why. Technology is one sector that’s in a constant state of flux. If you’re an insider, you’ll rarely find any dull moments. The last thing we saw was the dot-com bubble. Andreessen, however, “did not waste time being depressed.”

Andreessen has always been bullish about the tech industry and still is. Even when the majority of investors were selling their technology stocks, he remained positive. And that is the exact lesson he should have learned from his investments.

Even with his optimism in the tech sector, his capital firm cannot rock the VCs’ world without a comprehensive strategy that drives the growth of his company. Looking at a16z’s plan, we can see much more than just words on paper. Unlike his other “lowkey friends” at the Silicon Valey, his firm sits on the front row by pushing marketing. And this part doesn’t come from a traditional methodology but modeled more on a Hollywood talent agency.

That Optimist Leaning Hard to Marketing and Break the VCs’ Norm

From the starting, Andreessen Horowitz had a simple moral code: “We wanted to build the venture capital firm that we always wanted to take money from,” Horowitz says.

To get their foot in the gate as a new investment firm, they decided to take the opposite approach as the low-profile firms surrounding them. While building their venture capital firm, Andreessen and Horowitz took inspiration from Larry Ellison’s Oracle and its aggressive marketing during the corporate software battles.

The founders hosted expensive parties attended by the media and celebrities. The duo offered an endless stream of interviews to traditional and tech publications, praising their company and the businesses they invested in while disparaging their rivals.

One of the remarkable movements they’ve ever did is disregarding conventional wisdom and purchasing shares of companies like Twitter and Facebook when those firms had already reached billion-dollar valuations, despite the fact that they had initially made tiny seed payments to companies like Okta and Slack.

Strongly motivated by prior exits and some scrimping, the duo reinvested their money in the business, whose structure was modeled more on a Hollywood talent agency than a traditional venture capital firm.

Stage agnosticism was the following bullet point in their plan of attack. Whether they were able to invest in seed rounds or later stages of the startups they admired didn’t matter, they determined. They gave out smaller seed cheques to young businesses and didn’t hesitate to invest in shares of highly valued tech behemoths.

Neither received a salary for many years, and the company’s new general partners accepted lower pay than was customary. Instead, a large portion of its fees—the customary 2% of assets handled that goes toward paying all of a company’s expenses—were invested in a rapidly expanding services team that included professionals in marketing, business development, finance, and recruiting.

They hired the best marketing experts they could find and spent millions on helping develop the startups they invested in. In the hopes that the discovered synergy would cause all parties to orbit around Andreessen Horowitz, they also assisted in matching the businesses in their portfolio with governmental organizations and multinational enterprises. The idea was to use these services to make their deals more enticing and draw in the top companies in the world.

The strategy worked. The firm’s initial $300 million fund they managed to raise had an internal return rate (IRR) of 44%. They received an IRR of 16% on their second fund, which grew to be over $600 million. Their third and fourth funds, which had respective IRRs of 15% and 12%, both flew through the $1 billion mark.

Marc Andreessen’s estimated net worth as of February 2023 is above $1.5 billion. He sold his business, Netscape, to AOL in 1999 for $4.2 billion. Hewlett-Packard purchased “Loudcloud,” the hosting and software services business founded by Andreessen, in 2007 for $1.6 billion. He has contributed $4 million to more than 45 start-ups as an angel investor. When he sold his business, “Ning,” to the provider of digital lifestyle media, “Mode Media,” he received $150 million.

Three thousand entrepreneurs approach a16z annually with a “warm intro” from a contact. A16z puts money into fifteen. Of those, at least ten will fail, three or four will flourish, and one could become extremely wealthy and be referred to as a “unicorn” in the region.

The company wants to support three distinct individuals. They’re looking for a product innovator that has the drive and self-control to succeed as a CEO, is entrepreneurial and wants to establish a business. The outcomes are remarkable when people like that actually deliver and work hard for 10 years. They usually suffer a casualty if they falter on any of those three fronts.

Andreessen is generally reserved during pitch meetings, saving his passion for the transaction review when the company decides whether to invest. That’s where he asks questions that oblige his partners to envision a new world.

For the ride-sharing service Lyft: “Don’t think about how big the taxi market is. What if people no longer owned cars?” For OfferUp: “What if all this selling online—eBay and Craigslist—goes to mobile? How big could it be?”

Ben Horowitz, who is seated at the head of the table next to his co-founder, is a shrewd manager who uses his buddies Nas and Kanye West’s rap lyrics to encourage courageous thinking, but he doesn’t try to manage Andreessen.

“If you say to Marc, ‘Don’t bite somebody’s fucking head off!,’ that would be wrong,” Horowitz said. “Because a lot of his value, when you’re making giant decisions for huge amounts of money, is saying, ‘Why aren’t you fucking considering this and this and this?’”

Being a tech investor himself, he sets his eyes on every revolution that technology brings to the world, and since the crypto had been rocking the stage few years ago, this man, Andreessen could not be outside of the club. Even these days, this sector is still receiving his push.

Must-Win Moves to Push Forward Crypto Legislation

At a present time when technology companies have a nasty smell in Washington and as the fast-evolving crypto industry is attracting increasing criticism from lawmakers and regulators, Andreessen Horowitz is pursuing a particularly extremely ambitious plan: to both possess big chunks of the emerging world of digital currencies and have a hand in writing the rules for how it will function.

The company has engaged a variety of seasoned government employees to advance its objectives. They include Katie Haun, a former Justice Department prosecutor for cryptocurrency, Tomicah Tillemann, a former adviser to Joe Biden when he was a senator, and Brian D. Quintenz, who joined the effort only days after leaving the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, a regulator of cryptocurrencies.

With at least 50 crypto start-ups already funded and fresh agreements announced on a weekly basis, Marc Andreessen and his team are now the biggest investors in the industry.

A16z established a new $2.2 billion investment fund throughout the summer of 2021 to capitalize on the explosive expansion of cryptocurrencies and the underlying financial and technological framework.

The VC is also a major investor in Coinbase, one of the largest cryptocurrency exchanges, along with a number of newer start-ups. The firm has brought on so many people with industry expertise that the hiring spree has become a running joke on Twitter.

Marc Andreessen and Ben Horowitz, the founders of A16Z, have a vision of their company becoming the heart of a burgeoning new ecosystem of digital technology that will disrupt a variety of markets, including art, banking, finance, gaming, e-commerce, music, social networking, and telecommunications.

Andreessen Horowitz’s first cryptocurrency investment was in late 2013 with a $20 million initial bet on Coinbase. Soon after, Andreessen said in an opinion article in The New York Times that Bitcoin, the first cryptocurrency in history, signaled a revolutionary change in technology on par with the introduction of the personal computer in the 1970s and the internet in the 1990s.

In 2018, the firm started its first fund dedicated to crypto investments, raising $350 million. To abide by securities laws that restrict venture capital organizations’ allocations to riskier investments, such cryptocurrency businesses, it was created as a separate legal entity.

However, realizing the promise of cryptocurrency, Andreessen Horowitz changed from a venture capital firm to a registered investment adviser in 2019 — a pricey transition that put it under more regulatory scrutiny but freed it to explore cryptocurrency deals.

The company launched a second cryptocurrency fund for $515 million in 2020 and a third fund worth $2.2 billion this year.

Executives at A16Z immediately realized that playing a big role in establishing the regulations for these companies was necessary in order to deliver large returns on all of this investment.

Being a VC that aids the dominance of the tech sector seems to be successful, but may be just the first step in Andreessen’s plan. These days, a16z is trying to reach a higher level and step out of the standard of a normal capital firm, to adapt to severe changes in the industry.

The Next Grand Plan to Scale His Venture Capital Firm

Andreessen Horowitz is navigating the worst market for tech since the firm was founded. The company, Coinbase, which produced the biggest return for the company ever, is currently down around 80% on the stock market in 2022.

Other a16z investments that are currently publicly traded, like Airbnb and Affirm, saw a significant decline in share values over the last year. And a couple of its still-private businesses, including Instacart, have drastically reduced their valuations.

A16z has pledged billions to the digital asset market, yet one of the biggest exchanges in the crypto sector has collapsed, casting doubt on the future of the entire sector.

“Andreessen Horowitz has an awfully good track record to point to … But that was then, and this is now,” says Len Sherman, a professor at Columbia Business School.

Investors are not alone if they become restless and reconsider their bets in a changing market. Andreessen Horowitz itself is looking beyond the venture business, taking steps to become a more versatile financial creature that can tap new pools of capital and weather changes in the startup funding climate.

This transformation, which started a few years ago but is now even more urgent, tries to position the company as a sort of Western J.P. Morgan or Goldman Sachs. If there’s money to be put to work in technology, Andreessen Horowitz is there to play with it. The firm will introduce a private wealth management service in January 2023, allowing investors to invest the personal funds of business executives, according to a source.

A public market investing effort is being led by David George, formerly with General Atlantic. Additionally, a growing number of academics and policy experts are being hired to the payroll, which presently has over 500 employees as opposed to 240 in July 2021.

In a sense a16z is following its own recipe for turning startups into large companies—prioritizing growth while hoping to dodge the potentially fatal dangers that come with it. Based on the more than $35 billion the company has raised in the previous seven years; it is almost clear that a16z is making roughly $500 million a year from management fees alone. This amount is expected to increase as the company expands into new areas.

“They are running a lot of experiments,” says a former Andreessen Horowitz investment partner. “It seems to me relatively obvious that some will fail. The flip side is that some of them will work out.”