Pandora: The Once Leader in Online Music, Now Has to Climb Its Way Back Up Again

Founded nearly two decades ago, Pandora is a digital music veteran, older than its competitors.

But its troubles lie in the fact that it made itself a name in radio-style music streaming, in which listeners are given songs rather than selecting them—a platform that’s rapidly been overtaken by all-you-can-listen, on-demand music streaming.

Pandora’s new Premium offering (finally an on-demand service) is a classic case of too little, too late.

It’s looking more and more like the company is being edged out by newer, hotter rivals, and will go the way of Nokia—which absolutely dominated the mobiles phone market and made what is considered the first smartphone in the 1990s, only to see its lead be snatched away by rivals it didn’t see coming. (Apple, it seems, is a ruthless predator in both phones and streaming!)

The Online Music Shooting Star

Launched in 2005 by Will Glaser, Jon Kraft and Tim Westergren, Pandora is a freemium online radio service. The service, known for its ease of use and the ability for users to vote for songs they liked and disliked through thumbs-up and thumbs-down, became extremely popular and one of the true rising stars of the early digital music industry.

Pandora, unlike many other popular digital music streaming companies, did not strike deals directly with music labels, but instead operated as a pure play Internet Radio station. The company, therefore, had to pay royalties set by the US Copyright Royalty Board.

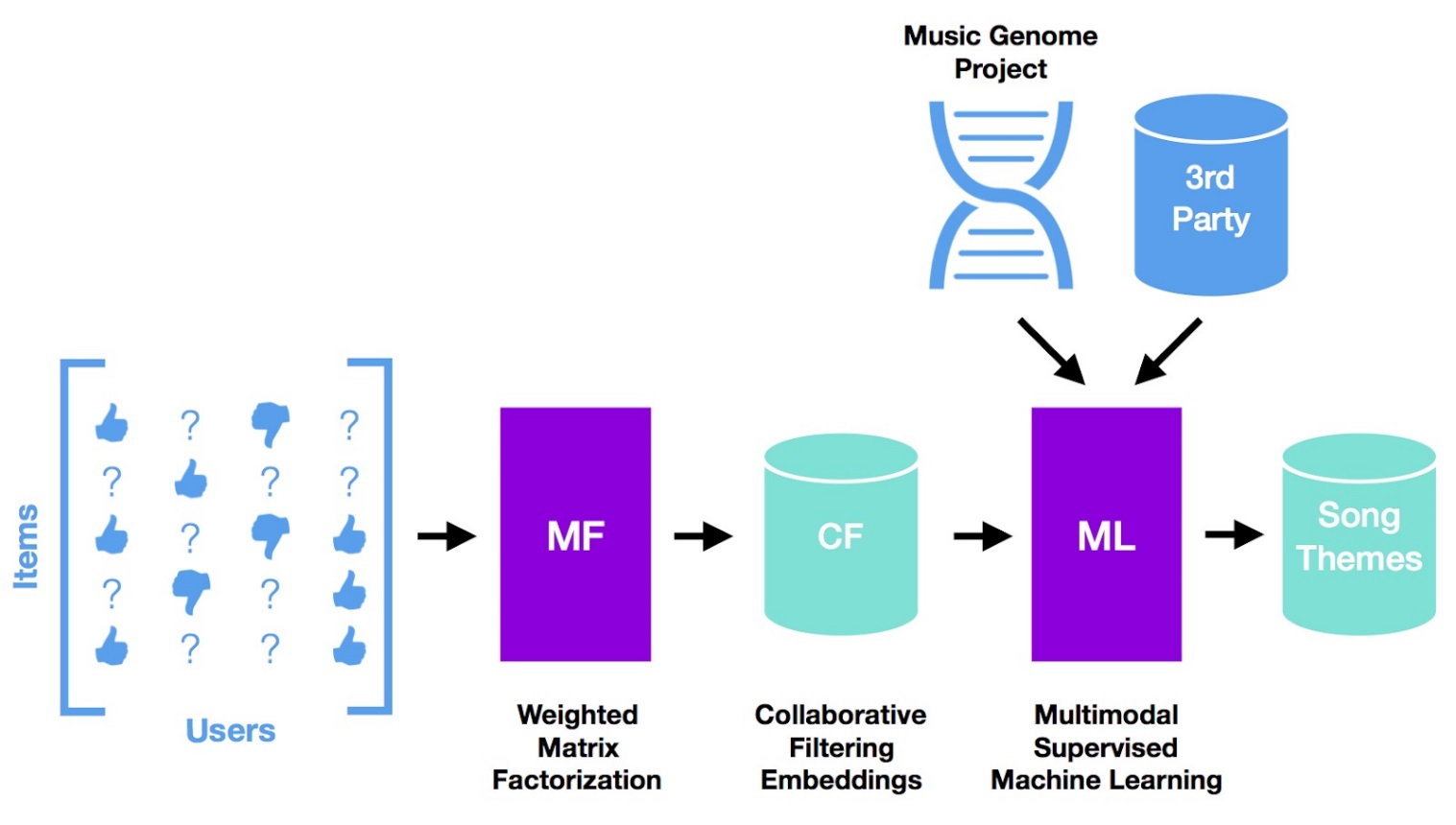

Pandora’s playlists can be tweaked by placing a thumbs up or thumbs down on each song. Not only that, but all of Pandora’s music selection is based on The Music Genome Project. This creation focuses on the qualities that the music possesses instead of categorizing songs by genre. For example, the workers who categorize this music focus on things like melody, harmony, composition, and lyrics.

In 2009, the company launched Pandora One, a service that allowed users for $4.99 to stream the radio stations without ads. In 2017, the company launched Pandora Premium.

For the years, the company was considered a shining star in the digital music space and continued to grow active users as well as revenues.

A Deeper Look Behind the Scenes

Pandora’s first data scientist, Gordon Rios, spends a great deal of his time understanding the intricacies of machine learning and music recommendations. One of the biggest reasons Pandora has remained popular (especially considering the looming spectre of rivals like Spotify) is rooted in its simplicity.

But according to Rios, there’s a definite trade-off. Ease of use can affect the complexity of the data and how sophisticated the data collection methods are. Fortunately, Pandora has several years’ worth of listening preferences and attributes for every listener cataloged and analyzed. Its recommendations are pivotal to its success, so a great deal of time and effort are poured into making those recommendations the best they can be.

It’s worth noting that Pandora has collected over 65 billion “thumbs” — a major indicator in how it matches musical tastes with listeners. And although Pandora faces some serious competition from other streaming services, like Apple Music, Spotify, and Slacker, their team believes that trying to correlate music tastes purely with which songs or albums a user bought (like iTunes does) is too short-sighted.

But the Star is Losing Its Shine

Interesting fact: In Greek mythology, Pandora is a woman who receives many blessed gifts from the gods, including the gift of music, the company’s founding team explained on its website. Naming the company after the world’s most foreboding tale wasn’t the original idea. But the name’s much more odious, cautionary association — Pandora’s box, a source of immense, cursed trouble — crept up when the company’s power began to fade in the last decade, as its customers defected to new streaming services!

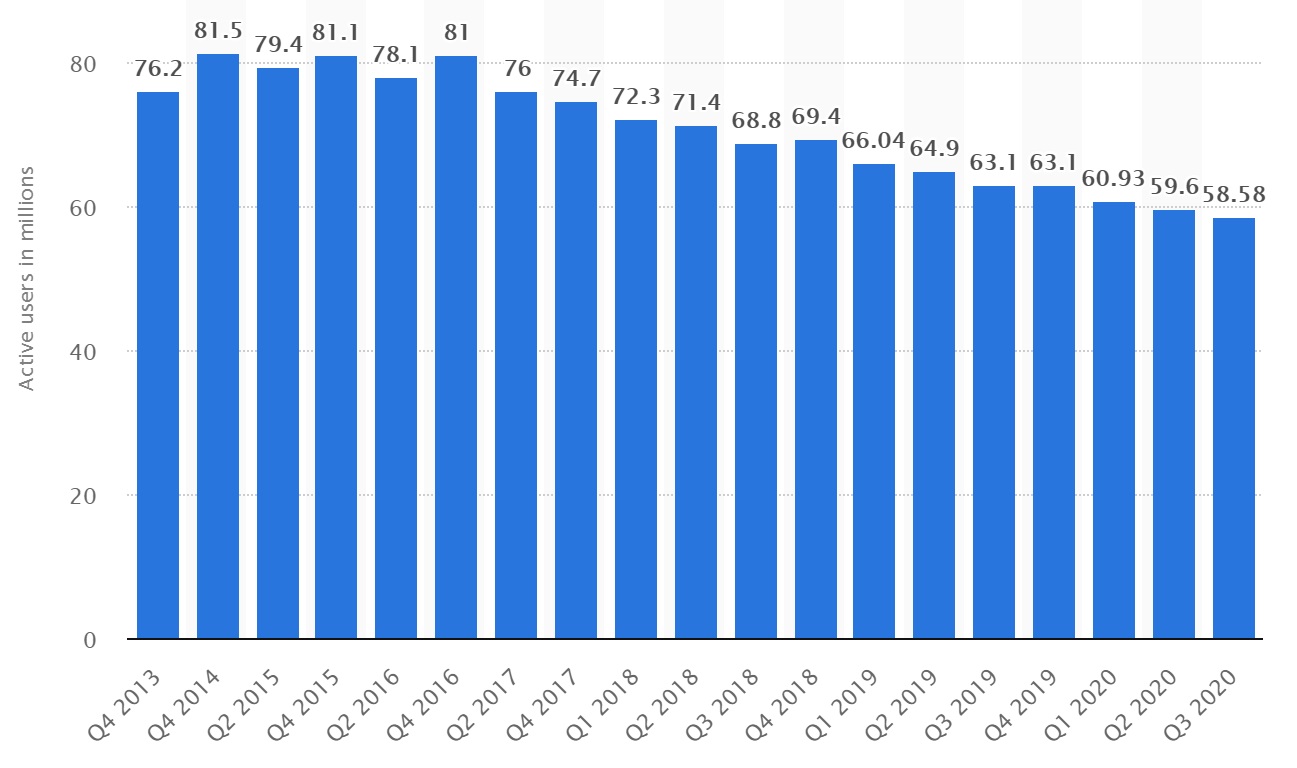

When Pandora went public in 2011 with a valuation of $2.6 billion and a leading US market share in online music consumption, Spotify barely entered the US and was valued at $1 billion, 2.6x less than Pandora at the time.

However, over the last 5 years, Spotify and other music streaming companies have re-shaped the digital music industry significantly – Pandora’s Monthly Active User growth has declined and according to industry experts, Spotify would overtake Pandora in Monthly Active Users as early as mid-2020.

When its former CEO & founder – Tim Westergren left in 2017, Pandora was in the middle of a major upheaval. Pandora had grown to become a public company that generated almost $1.5 billion in revenue that year, but its shares had plummeted 35% as audiences migrated away from online radio to on-demand streaming.

Pandora’s Problems

What has happened that the clear incumbent leader is losing its power? The below outlines the issues with the Pandora model:

“Want to listen to your favorite song? Please wait.”

For the longest time, Pandora’s personalized radio channels, allowing consumers to discover new music, were a big hit and helped the company grow its user base. However, then came Spotify – allowing customers to listen to their favorite songs, whenever they want, as many times as they want. At the same time, until the launch of Pandora Premium in 2017, Pandora did not allow users to skip songs beyond 30 skips in 24 hrs. Therefore, users could not listen to their favorite songs.

“Sitting on a flight? Sorry, can’t get online radio.”

While Spotify, Apple Music and other streaming services allow premium users to download songs and play them offline (e.g., when in a low or no network environment), Pandora, until 2017, did not allow users to listen to music offline.

“Want to create your own playlist? Nah, we’ll do it.”

While Pandora’s custom radio stations are a great feature for music discovery, they limit the personalization opportunities within the platform. While Spotify, Apple Music and other subscription companies allow users to create their own playlist, with their own individual songs, thereby creating very sticky consumers, Pandora, until 2017, did not allow for this feature.

The three above mentioned points show the critical importance of being close to the consumer and understanding user needs and demands in order to stay relevant in a digital world. Apart from these user-centric issues, Pandora is facing another challenge, which other players are not facing:

“A global business? Nope, not possible.”

While Spotify, Apple Music and other premium streaming platforms have always been striking deals with music labels directly, Pandora, as an online radio is tied to local radio laws in the countries that it operates in and therefore, has not been able to launch in any other geography than the US, New Zealand and Australia, while others have been able to create a global business.

Eventual Buyouts

In 2016, after years of losing consumers to competitors, Pandora finally announced that it would give in to consumer demands and launch its own premium subscription service for $9.99 per months. It had acquired Rdio for $75M a year before and planned to launch Pandora Premium in March 2017.

In 2018, the company got acquired by SiriusXM at $10.14 per share, a 37% discount from the initial IPO price of $16. It remains to be seen whether Pandora will be able to catch up with its strong competition.

Better Late than Never!

After years of customizing playlists to individual listeners by analyzing components of the songs they like, then playing them tracks with similar traits, the company has started data-mining users’ musical tastes for clues about the kinds of ads most likely to engage them.

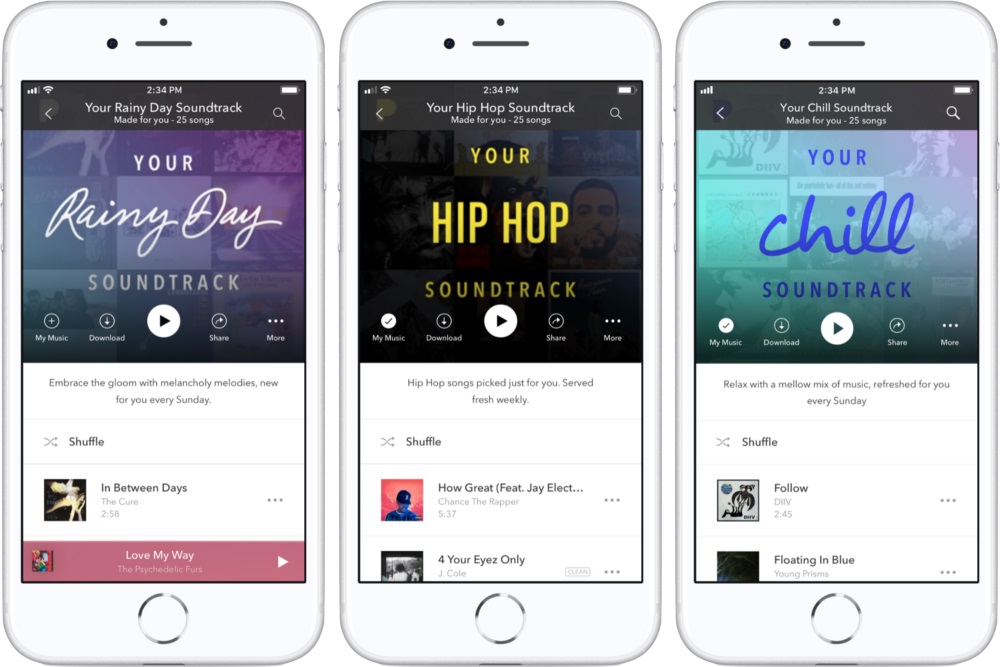

Personalization has become a key selling point for today’s streaming music services. And though Pandora led in this area in years past thanks to its Music Genome, thumbs up and down signaling buttons and its personalized stations, it has since ceded ground to Spotify, whose bevy of algorithmically updated playlists, led by Discover Weekly, have addicted users to its service.

This revamped Pandora app is a way for the now SiriusXM-owned company to fight back by highlighting what it does have that others don’t.

Convergence of Science and Music

The beating heart of Pandora — its Music Genome Project — was originally a commercial failure. The idea was to have musicians listen to and decode a song’s “DNA” and then categorize it according to different musical qualities such as meter and tonality. Numbers are assigned to the over 450 different attributes, and Pandora’s algorithm went to work, finding other songs that match these same qualities.

Originally, the plan was to license the Music Genome Project commercially, but when that was met with a tepid response, Pandora itself was founded – creating the foundation for the music streaming service we all know and love.

But that’s not even scratching the surface. According to Pandora’s Chief Scientist and VP of Playlists (yes, that’s his real title), Eric Bieschke, notes that the context of how, where and on what device the user listens to music are also part of discovering their tastes.

Because Pandora is available on everything from car stereos to mobile phones, the music people choose to listen to at different times of the day and on different devices can be radically different from each other. Bieschke explains that what you listen to in the morning at the gym through your mobile device can be markedly different than listening to music in the evenings when winding down after a long day. It’s Pandora’s job to incorporate things like the time of day to a user’s listening preferences and ensure that the next song on the playlist is one they’ll love.

Pandora’s algorithms also weigh different factors according to the actions the user takes (or if they take no action at all) when listening. The rarest and most valuable insights come in the form of a “thumbs up/thumbs down”. This simple action has an immediate effect on the next song you hear.

Simply skipping a song, Bieschke explains, doesn’t carry as much weight with the algorithm, since the intent behind the skip could be anything from “I’ve heard this before” to “I’m not in the mood for this right now.” However, if you don’t skip songs regularly and then start to do so considerably, Pandora takes note of this and adapts your playlist accordingly.

Listen to Pandora, and It Listens Back

“It’s becoming quite apparent to us that the world of playing the perfect music to people and the world of playing perfect advertising to them are strikingly similar,” says Eric Bieschke.

Consider someone who’s in an adventurous musical mood on a weekend afternoon, he says. One hypothesis is that this listener may be more likely to click on an ad for, say, adventure travel in Costa Rica than a person in an office on a Monday morning listening to familiar tunes. And that person at the office, Mr. Bieschke says, may be more inclined to respond to a more conservative travel ad for a restaurant-and-museum tour of Paris.

“The truth is, purchase data alone can only do so much. There’s a distinct division between the music people buy and the music people want to listen to at any given moment. Pandora makes allowances for the first and wholly embraces the second.”

Pandora is now testing hypotheses like these by, among other methods, measuring the frequency of ad clicks. “There are a lot of interesting things we can do on the music side that bridge the way to advertising,” says Mr. Bieschke, who led the development of Pandora’s music recommendation engine.

A few services, like Pandora, Amazon and Netflix, were early in developing algorithms to recommend products based on an individual customer’s preferences or those of people with similar profiles. Now, some companies are trying to differentiate themselves by using their proprietary data sets to make deeper inferences about individuals and try to influence their behavior.

This online ad customization technique is known as behavioral targeting, but Pandora adds a music layer. Pandora has collected song preference and other details about more than 200 million registered users, and those people have expressed their song likes and dislikes by pressing the site’s thumbs-up and thumbs-down buttons more than 35 billion times. Because Pandora needs to understand the type of device a listener is using in order to deliver songs in a playable format, its system also knows whether people are tuning in from their cars, from iPhones or Android phones or from desktops.

So, it seems only logical for the company to start seeking correlations between users’ listening habits and the kinds of ads they might be most receptive to.

“The advantage of using our own in-house data is that we have it down to the individual level, to the specific person who is using Pandora,” Mr. Bieschke says. “We take all of these signals and look at correlations that lead us to come up with magical insights about somebody.”

People’s music, movie or book choices may reveal much more than commercial likes and dislikes. Certain product or cultural preferences can give glimpses into consumers’ political beliefs, religious faith, sexual orientation or other intimate issues. That means many organizations now are not merely collecting details about where we go and what we buy, but are also making inferences about who we are.

“I would guess, looking at music choices, you could probably predict with high accuracy a person’s worldview,” says Vitaly Shmatikov, an associate professor of computer science at the University of Texas at Austin, where he studies computer security and privacy. “You might be able to predict people’s stance on issues like gun control or the environment because there are bands and music tracks that do express strong positions.”

Pandora, for one, has a political ad-targeting system that has been used in presidential and congressional campaigns, and even a few for governor. It can deconstruct users’ song preferences to predict their political party of choice. (The company does not analyze listeners’ attitudes to individual political issues like abortion or fracking.)

During the next federal election cycle, for instance, Pandora users tuning into country music acts, stand-up comedians or Christian bands might hear or see ads for Republican candidates for Congress. Others listening to hip-hop tunes, or to classical acts like the Berlin Philharmonic, might hear ads for Democrats.

Because Pandora users provide their ZIP codes when they register, Mr. Bieschke says, “we can play ads only for the specific districts political campaigns want to target,” and “we can use their music to predict users’ political affiliations.” But he cautioned that the predictions about users’ political parties are machine-generated forecasts for groups of listeners with certain similar characteristics and may not be correct for any particular listener.

Shazam, the song recognition app with 80 million unique monthly users, also plays ads based on users’ preferred music genres. “Hypothetically, a Ford F-150 pickup truck might over-index to country music listeners,” says Kevin McGurn, Shazam’s chief revenue officer. For those who prefer U2 and Coldplay, a demographic that skews to middle-age people with relatively high incomes, he says, the app might play ads for luxury cars like Jaguars.

In its privacy policy, Pandora describes the types of information it collects about users and the purposes — music personalization and ad customization — for which the information may be employed. Although users may elect to pay $59.88 annually to opt out of receiving ads, advertising on the free service accounts for the bulk of Pandora’s revenue. Out of $1.72B in revenue in the 2019 fiscal year, advertising generated $1.2 billion.

Pandora’s inferences about individuals become more discerning as time goes on. How we think about the ethics and accuracy of algorithms is another matter.

“I’m optimistic that the benefits to society will outweigh the risks,” Professor Shmatikov says. “But our attitudes will have to evolve to understand that now everybody knows more about who we are.”