HubSpot: The Tech Start-up That Coined “Inbound Marketing” In Early 21st Century

With a full suite of offerings and hundreds of application integrations, HubSpot has now transformed itself into a platform vendor aimed at winning a greater share of larger mid-market accounts (200 to 3,000 employees).

Shares of HubSpot rose 41.5% during the first half of 2020. In addition, HubSpot reported first-quarter earnings that beat analyst expectations, while giving optimistic commentary on the future, fueling further gains. A combination of steady subscription revenue and low interest rates helped contribute to HubSpot’s rise.

Gaining Early Traction by Practicing What They Preach

HubSpot was founded in 2006 by Brian Halligan (CEO) and Dharmesh Shah (CTO). The pair met in 2004 during their MBA at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, which later became the company’s headquarters.

At that time, customers became increasingly annoyed by the experience of surfing business websites. These were often clotted with intrusive and annoying ads and pop-ups, causing users to ignore them and businesses to see their customers abandon them.

Before the pair actually developed any pieces of software, they tested their idea by creating the HubSpot blog. Once they saw people engaging with their content (and thereby confirming some of the theories they had about Inbound Marketing), the business case for HubSpot was confirmed.

The Birth of Inbound Marketing

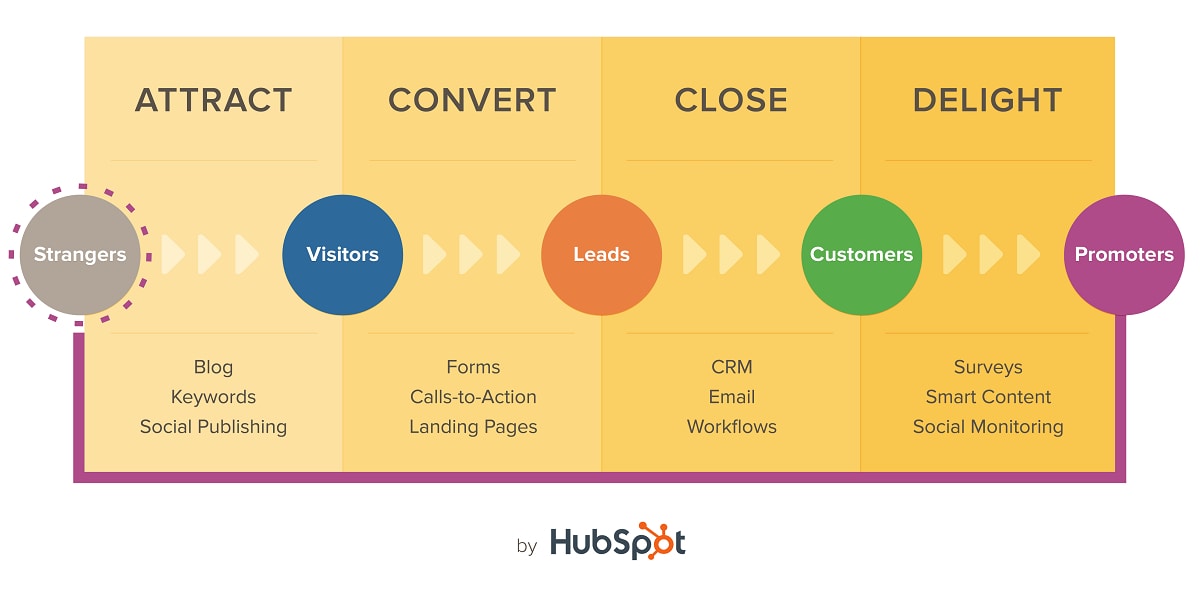

Inbound marketing is a set of techniques that allow businesses to attract customers via different channels. Rather than outwardly pushing the brand (e.g. through banners or TV ads), inbound marketers try to persuade customers once they enter a platform.

When Brian and Dharmesh launched HubSpot, the phrase “Inbound Marketing” didn’t yet exist, but the concept was already there, prior to 21st century. Interestingly enough, HubSpot actually coined the term “Inbound Marketing” back in 2006, made it an integral part of their brand, and started evangelizing this approach to marketing with the zeal of a convert. The founders even published a book covering the topic in more depth.

HubSpot CMO Mike Volpe says that inbound leads are generally cheaper to acquire, and it should come as no surprise that inbound marketing has been critical to HubSpot’s growth:

“I cannot emphasize enough the importance of inbound marketing in our growth. I know I am biased, but that does not make it a lie.”

Benefits of Inbound Marketing include:

- Decreasing over-reliance of one channel by establishing different customer acquisition funnels (e.g. blog, YouTube channel, social media)

- Companies can increase trust with the product as they publish content around the topic and visibly gain expertise in the eye of the customer

- Reaching a targeted audience, for instance by writing content around specific search terms

- Lower cost as companies don’t have to pay for ads

The company’s inbound marketing strategy covers the spectrum, but one area in which they’ve really excelled is content marketing. From the outset, HubSpot has offered resources like expert blog posts, webinars, and tools.

Through focusing on inbound marketing as a means of establishing themselves as an authority in the field, HubSpot was and is able to generate a huge volume of relatively low cost (especially when compared to outbound marketing), high quality leads.

Building a Growth Framework Towards a $100M Product

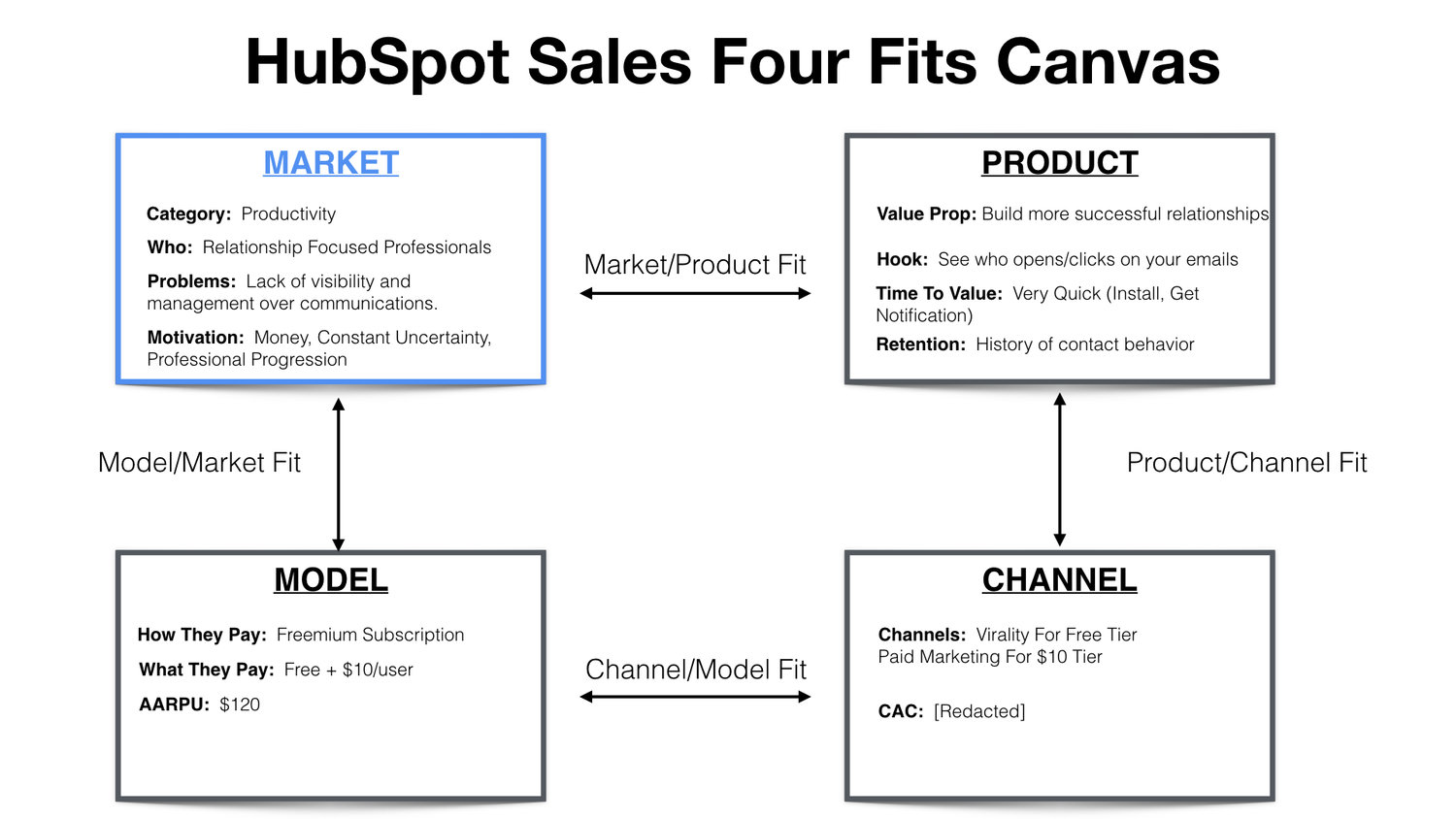

Beginning with Market Product Fit

The road to 100 million dollars didn’t start with product. Because starting with product puts the cart before the horse; you are creating a solution, and then trying to fit it to the problem! We need to do the reverse: Begin with the market, then look at the product. The problem your company exists to solve lies within your market and target audience, not within your product.

Christopher O’Donnell, Dan Wolchonok, and a few other engineers did this initial work and built the very first version of HubSpot Sales (then known as Signals). The total team size was about 7 people and the product had about 2,000 WAU (weekly active users), and perhaps a few thousands in MRR (monthly recurring revenue).

HubSpot had spent countless hours talking to customers to define the market and audience hypotheses more concretely. They built out detailed personas, but the four main things they defined were:

- Category: Sales Software.

- Who: The individual contributor. There were also two sub-types of ICs: SDRs and Account Reps.

- Problem: Not knowing where a prospect or client stood in the process.

- Motivation: A couple of motivations: 1) Money. Knowing where a prospect was led to better prioritization and selling, which led to more closing. 2) Uncertainty. The target audience’s life was filled with constant uncertainty. Relieving that uncertainty was a big deal.

After making sure they understood the market, HubSpot then defined the four key areas of product hypotheses that aligned with the four areas they identified in the Market:

- Core Value Prop: What was the core value prop of the product? How did it tie to the core problem?

- Hook: How could the core value prop be expressed in the simplest terms?

- Time to Value: How quickly could they get the target audience to experience value.

- Stickiness: How and why will customers stick around? What are the natural retention mechanisms of the product?

The first version of the product was extremely simple. It consisted of a Chrome extension that, with a click of a checkbox, let you track your emails and get instant notifications on who opened and clicked on your emails. You got up to a couple hundred notifications for free, or paid $10 for unlimited notifications.

But just because they had hypotheses, doesn’t prove that they had Market Product fit. The best indication for Market Product Fit are retention curves that flatten. This indicates that users are receiving real value over a period of time.

HubSpot had solid hypotheses for 3 of the 4 elements, but they were missing hypotheses around their channels. In the early days of every product, most of your time is spent on proving your Market Product Fit hypotheses. But that doesn’t mean you can ignore the others. You need to have hypotheses for all the elements. The fits work together and influence each other.

If you treat them in isolation, you will end up trying to fit a square peg in a round hole. Which brings us to phase two, defining and proving our Channels.

Finding Product Channel Fit and Channel Model Fit

Product Channel Fit will make or break your growth. Product Channel Fit states that:

“Products are built to fit with channels. Channels do not mold to products. The reason for this is that you do not define the rules of the channel. You define your product, but the channel defines the rules of the channel.”

HubSpot’s product had a few elements: very quick time to value; simple hook; broad value prop; transactional model. These elements of the product led to building two main channel hypotheses: virality; paid marketing.

But they also needed to make sure that these channel hypotheses aligned with Channel Model Fit. An engineer at HubSpot explained about Channel Model Fit:

“Every business lives on the ARPU (Average Revenue Per User) ↔ CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) Spectrum. On far left you have businesses that have low ARPU and as a result have to use low CAC channels to drive customers. On the far right you have businesses that have high ARPU and as a result are able to use high CAC channels. The middle is the danger zone where your ARPU is too high and presents to much friction for the low CAC channels to be effective, but too low to support the higher CAC channels.”

So where did HubSpot Sales exist on this spectrum? Did their channel hypotheses fit?

They did indeed. Virality fit with their free tier (no ARPU, low friction). Paid Marketing fit with their $10/user tier which had higher friction but higher ARPU to support the channel.

Once HubSpot laid out these hypotheses, the company spent the next few months proving them out, and thankfully they were correct. A solid incentivized viral loop, along with Facebook Ads, made up 70% of their growth. They went from 2K WAU to 100K WAU and meaningful MRR very quickly.

The issue was that there are only 2-3 million salespeople in the target market if you take out brick and mortar retail salespeople and outside salespeople, who weren’t a good fit for their product. At their $120 ARPU they would have needed 1 million paying customers (or 33% – 50% of the target market), which also meant they needed to acquire 10 million+ free users, given their conversion rates. Those numbers didn’t feel reasonable for their current definition of the market.

Most low ARPU freemium businesses (Dropbox, Evernote, etc.) address much larger markets. Interestingly, around this time HubSpot revisited their personas by interviewing a lot of customers. And they happened to find totally new segments of users using and paying for the product – small business owners, recruiters, marketers, and more. They called the group collectively, Relationship Focused Professionals. These were professionals who were communicating externally a large portion of their day.

HubSpot redefined their Market hypotheses and checked to see if everything else still fit (it did). This new market definition was much bigger, and the Model Market fit equation made a lot more sense.

About a year in growth was cranking. HubSpot had hundreds of thousands of WAU’s, and MRR was following. They had found the four fits among their initial target audiences and were looking to layer on more growth.

Talking to their paying customers, HubSpot realized there was clearly a large segment that had a higher willingness to pay. The company started exploring additional features and introduced a new tier to the product priced at $25/month.

But just because there is a high willingness to pay, and HubSpot can build the features, doesn’t mean they’ve hit on a sustainable growth model. The $25 tier landed squarely in the danger zone of the Channel Model Fit spectrum.

The $25/user/month price point created too much friction to effectively drive with the lower CAC channels of virality and paid that were working on the free and $10 tier. So they tried implementing content and inside sales to drive sales of the $25 tier. Content and inbound sales was the bread and butter of HubSpot’s history.

But in a company full of experts around the channels, it just didn’t work. The ARPU of the $25/user tier just didn’t support the higher CAC channels of content and inbound sales. In addition, it just wasn’t driving the volume needed to build a big business at that price point.

As a result, they eliminated the $25 tier and created a $50 per user per month tier, adding an additional feature or two to the product. With the hard work of Sales Director Mike Pici and others, the machine started to click, and the economics started to work out.

Strategy Shift, Changing Everything

About 18 months in after a number of twists and turns, HubSpot had the four fits. They had grown from a few thousand WAU’s, to hundreds of thousands and a couple thousand in MRR to a few hundred thousand in MRR.

However, their biggest shift was still ahead.

“I remember sitting in one of our monthly management meetings, reviewing the numbers and progress of the business and someone made the observation: these customers look really different from the core HubSpot customer. The statement lingered in the air with a lot of weight,” a former marketer at HubSpot shared.

HubSpot Marketing had a completely different market, model, and Model-Market fit. HubSpot Marketing targeted mid-market customers and therefore had a model with an ARPU of $8K – $10K. They lived in a completely different place on Model Market fit.

The mission for HubSpot Sales was to build a $100M line of product with a freemium model. To do that, they had a lower ARPU and to achieve model market fit needed to target a broader audience, which included a lot of small businesses and business owners.

A few years earlier, HubSpot had taken a big bet to focus on the mid-market. It was a big hard bet that after a lot of work paid off for the company. The idea of veering away from that again caused a lot of pain.

“The suggestion was raised that we take what we had, and just start focusing on targeting the mid-market. The problem was that would have broken HubSpot Sales’ Model Market Fit, and would have taken us off track in building a $100M line of business.”

There were really only two choices:

- Choose the Model: Keep the freemium, low friction, touchless, and low ARPU model, and embrace a different type of market veering away from the core mid-market customer that HubSpot had seen so much success with. This also meant they needed to stay on a path where they were building a product for that broad audience and double down on virality and paid acquisition to keep the fits aligned and continue to grow.

- Choose the Market: Focus on the mid-market customer. As a result, change everything else including the product, the channels, and the model in order for the four fits to align. (Remember, if you change one element you need to change all the others to fit).

It was a hard and painful choice. Eventually, HubSpot decided to choose the market. A number of strategic shifts fell out of that:

- Product – They cut the $10 tier and moved those features to the $50 tier. In addition they doubled down on additional features within the $50 tier targeted at the problems of their new market definition.

- Channels – They massively reduced efforts on virality and paid, and doubled down on content marketing and sales to align Product Channel Fit.

- Model – They doubled down on the $50 tier selling minimum seat, annual deals, which increased the ARPU to align Channel Model Fit and Model Market Fit.

The changes were painful. HubSpot had spent 18 months going after a different strategy and learning a ton about new channels and models. But ultimately, changing course was the right decision. Making the shift unlocked the next major phase of growth, leveraged the DNA core to rest of the business, and aligned better to the overall mission of the company.

Key Takeaways from the 4-Fits Framework

- You need all four fits to align to be able to grow into a $100M company in a venture-backed timeframe. Getting all four fits to align is incredibly difficult, which is why these types of wins are so rare. If you don’t have all four fits, you may still have a successful company, but either it will grow slower than the venture timeframe or it will have a lower ceiling.

- When you change one component within the framework, you need to revisit and change the rest, just as they did with the model vs market choice. One of the biggest mistakes is thinking you can just change one element, and all will be fine. It is part of the reason why moving up and down market is so difficult.

- The fits are always changing and evolving. A market can shift, a new channel can emerge, your channel can shut down, and so many other things. In the earliest days of start-up, it’s vital to revisit this framework monthly as the pace of change is quicker.

- If you are building a new line of business inside a larger company, like they were at HubSpot, you should avoid pursuing a path where all the components of the framework are different than those of the existing core business. If all of them are different, and there is no institutional knowledge, distribution, or other components to leverage, then that new business should realistically live as a different company, not a line of business within the larger company.

HubSpot’s digital “inbound” marketing tools are actually well-suited for the pandemic crisis, as HubSpot’s technology suite helps companies digitize their marketing to reach customers in a more efficient manner. As such, many companies could still benefit from HubSpot’s products, even in a socially distanced economy.

Management also noted that HubSpot had worked with customers by offering discounts and downgrades to cash-strapped clients during shutdowns, keeping them in the HubSpot ecosystem rather than letting them go. That resilience and customer-friendly ethos should serve HubSpot in good stead as the economy recovers.