Rite Aid Free Fall – An Explosion of Built-in Tumors

Rite Aid stock is slumping down, investors are shaking. If you had chosen to invest $11,000 in the pharmacy during their 1999 peak, your investment would have dwindled to less than $1 today.

Things are not looking good for Rite Aid, one of America’s biggest drugstore chains has been having trouble so much that they have filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on October 2023.

The light is getting dimmer for the pharmacy giant since all the doors out are closing one by one. However, if you have been putting your eyes on the retailer over the last two decades, this end is not something shocking, but instead, anticipated.

The fact is Rite Aid hasn’t been doing good these years, the company has been trying to build back toward profitability but unable to make up for the losses in recent years. This is a sad ending which unveiled many reasons behind the free fall of the behemoth. But first, let’s go all the way back to the time when everything was gold.

From an Inspirational Tale to Deep in Red

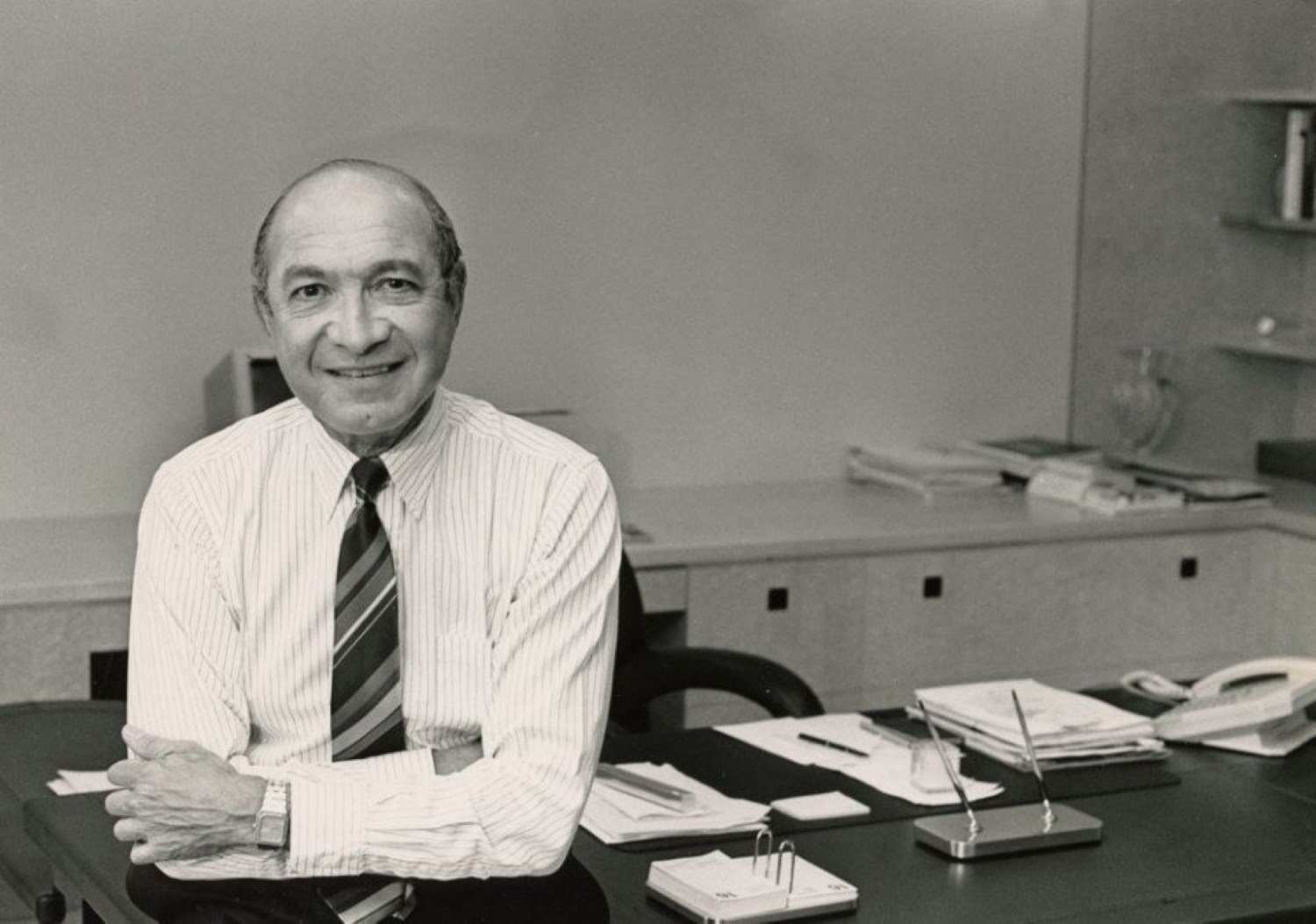

Founded by Alex Grass, the company has its roots in a challenging upbringing for its founder. Born shortly before the Great Depression, Grass faced financial struggles as his father passed away when he was just nine years old.

Despite these hardships, Grass persevered and went on to earn a law degree by the 1950s. He entered the professional arena by working for his wife’s family, who owned a grocery distribution company. The landscape of retail shifted in the early 1960s with a Supreme Court decision prohibiting companies from enforcing minimum prices for products sold by retailers. This legal development intensified competition among retailers.

Alex Grass seized an opportunity by opening a small discount store in Scranton, Pennsylvania, specializing in health and beauty products. He dubbed it Thrift D Discount Center to highlight its budget-friendly approach, and right out of the gate, it hit the ground running. In its first year, the store raked in $750,000 in sales—triple what Grass had expected.

Buoyed by this success, Grass expanded his retail empire throughout the northeastern U.S. In just six years, by 1968, there were already over 50 stores in operation. Sensing the importance of the pharmacy aspect, he rebranded the enterprise as Rite Aid.

This move coincided with Rite Aid going public, pulling in over $8 million in funding. A substantial chunk of that capital was earmarked for the opening of new stores, propelling Rite Aid’s growth even further.

In the following decades, Rite Aid sustained its growth trajectory by leveraging an extensive array of private-label products, staying technologically current with computer systems, and strategically acquiring regional drugstore chains to establish a nationwide presence. By the 1990s, the company had burgeoned to nearly 3,000 stores, securing its position as the largest chain of drug stores in the United States.

For the first 30 plus year, Rite Aid stood out as a success story. However, the tide took a turn in 1995 when Alex Grass stepped down from his roles as CEO and chairman of Rite Aid, this was when everything started to look bad.

When the Captain Can’t Lead– Sending the Giant to a Blind Alley

His son, Martin Grass, took over as the company’s new boss, and most people would agree that he was among the worst executives to have ever been placed in command of a business this size.

Under the lead of Martin, he had been sending the company down many blind alleys, one of these bad moves was overextending. The new strategy was to aggressively expand Rite Aid, which was already the largest pharmacy.

Their rise up to that point had been attributed to a number of regional purchases, but now they were spending billions of dollars acquiring large competitors.

Right off the bat, within a year, Rite Aid went for a big move by trying to snatch up Revco, a popular drugstore chain based in Cleveland. It could’ve been their largest acquisition ever, but the FTC threw a wrench into the works, raising antitrust concerns and putting the brakes on the whole deal.

Not to be discouraged, the following year saw Rite Aid successfully bagging Thrifty Payless, the West Coast’s biggest drugstore chain, boasting over 1,000 locations when you factor in their debt. The price tag for this move? A hefty $2 billion. Wrangling such a massive operation into Rite Aid’s business turned out to be quite a challenge.

In 1999, they decided to roll the dice again, shelling out another $1.5 billion to acquire a pharmacy benefits manager. Pretty gutsy moves, especially considering they were stretching their financial limits to make it all happen. Rite Aid had to lean heavily on borrowing to fund these deals, putting the company in a financially precarious position.

As the decade drew to a close, Martin Grass had propelled Rite Aid’s sales to more than double, but concurrently, their debt had ballooned to an unsustainable level. The company was already grappling with challenges in meeting its financial obligations.

On a positive note, Rite Aid successfully orchestrated a turnaround. Introducing new leadership, they initiated the strategic closure of underperforming stores, refinanced their debt, and offloaded their pharmacy benefits manager to alleviate some of their financial burden.

By the mid-2000s, their debt had been slashed by half from its previous levels, and the company reported a genuine profit for the first time in six years. However, the optimism is tinged with disappointment, as despite narrowly avoiding bankruptcy and achieving a notable recovery, Rite Aid found itself repeating the same mistakes.

Overextending, yet again.

In 2006, likely feeling ambitious and healthy after their big recovery, they announced a new acquisition that was even larger than any before it. They bought Eckerd and Brooks drug stores and quickly converted them into Rite Aids.

For one year, they operated more than 5,000 stores, their all-time high before they started closing them again. Unfortunately, this was terrible timing, as they had gone deeper into debt right before a major recession. When you have $6 billion in debt, it’s hard to turn a profit when you’re paying so much interest.

Rite Aid has recorded losses of about $8 billion and paid interest charges of nearly $10 billion since 1995. It’s worth mentioning that their biggest gain in 2015 was mostly due to a tax benefit, while their biggest loss in 2009 was primarily from a Goodwill impairment charge related to the big Eckerd acquisition, which quickly lost a significant portion of its value.

It’s disappointing that they were thrust back into problems following a commendable resurgence due to a poorly thought out and risky acquisition. They were in an unstable position, and with the unhealthy financial graph, it doesn’t look tasty to investors, which leads to something even crazier, accounting fraud.

Accounting Fraud – Tried to Make a Good Looking Cake

When Rite Aid’s business began to suffer in the late 1990s, they turned to lying about their financial accounts to give an appearance that the company was doing far better than it actually was.

After reading those statements, investors made their financial decisions under the false impression that the company had substantial earnings, which usually resulted in an artificially inflated stock price.

For over two years, Rite Aid deceitfully overstated their net profits by $1.6 billion every quarter by using a variety of accounting techniques. The SEC referred to this as one of the most heinous accounting frauds in recent memory, and these reports had to be restated thereafter. This is when their stock price really started to plummet, and people did not want their money invested in Rite Aid after learning about this.

Five executives from the company ultimately went to prison in connection with the fraud, including Martin Grass, who was charged with concealing related party transactions that enriched himself at the expense of shareholders.

Martin L. Grass was sentenced to eight years in prison for his role in a massive accounting fraud at the drugstore chain his father co-founded.

The sentence is one of the harshest handed out to a top executive in the recent wave of accounting scandals. Even if he gets the maximum time off for good behavior, the 50-year-old Mr. Grass will serve a minimum of about six years and 10 months, prosecutors said.

Judge Sylvia Rambo, of U.S. District Court in Harrisburg, Pa., also fined Mr. Grass $500,000 and gave him three years’ probation. The eight-year prison sentence she handed down is less severe than the maximum of 10 years Mr. Grass could have received, but harsher than the seven years recommended by prosecutors.

Mr. Grass choked up briefly as he addressed Judge Rambo before sentencing, saying he was “truly sorry” for the harm he caused to Rite Aid, its employees and its shareholders. He said Rite Aid was “more than a job for me,” adding that he worked at the family business during summers as a teenager, then later was ambitious to expand it rapidly.

“However, as it turned out, I tried to do too much too fast,” he said. “In early 1999, when things started to go wrong financially, I did some things to try to hide that fact. Those things were wrong. They were illegal. I did not do it to line my own pockets.” Mr. Grass also admitted asking others, including his former secretary, to lie to a grand jury.

Most people expected Martin Grass to spend 10 years in jail, but he was released after six and barred from ever again serving as an officer or director of a public company.

Falling Way Behind the Other Players in the Game

In the fiercely competitive pharmaceutical retail arena, Rite Aid found it challenging to match the scale of larger competitors like CVS and Walgreens. The emergence of e-commerce giants, particularly Amazon, exacerbated Rite Aid’s struggles, steadily eroding its market share and pushing the company perilously close to the edge.

The pursuit of these risky decisions, motivated by a desire to keep pace with industry leaders, ultimately did not yield the anticipated results for Rite Aid.

In 2018, after failing to buy the whole company, Walgreens did buy almost 2,000 Rite Aid stores because they needed the money to pay off some of that debt. But selling half of your business to a direct competitor does not help you become more competitive.

Today, Walgreens and CVS have around 9,000 stores each, whereas Rite Aid is in a distant third with about 2,000 of them. It’s the kind of store where convenience is extra important. People will commonly go to whichever one is closer, and for most people today, that store is no longer Rite Aid.

Not to mention the competition when it comes to their everyday things from internet shops and pretty much everywhere else. It’s difficult to stay up with some of the fierce rivals out there, particularly after experiencing a prolonged period of unstable finances.

Ignoring “Red flags” – Filling Illegal Opioids Prescriptions

One of the main reasons behind the decline is lawsuits. Years ago, there was a significant class-action settlement related to the accounting scandal and other smaller issues. However, the most pressing threat right now is related to their prescriptions and the opioid crisis.

On March 13, 2023, the U.S. government sued Rite Aid, claiming the pharmacy chain overlooked warning signs while improperly filling hundreds of thousands of prescriptions, including opioids. According to the Department of Justice, Rite Aid repeatedly filled unnecessary, off-label, or improperly issued prescriptions from May 2014 to June 2019.

“The Justice Department is using every tool at our disposal to confront the opioid epidemic that is killing Americans and shattering communities across the country,” Attorney General Merrick Garland said in a statement.

Rite Aid pharmacists faced accusations of neglecting clear indicators of misuse, notably in prescriptions for “trinities” – a mix of opioids, benzodiazepine, and muscle relaxants favored by drug abusers for heightened euphoria.

The Justice Department further alleged that Rite Aid deliberately removed internal warnings from some pharmacists about suspicious prescribers, like “cash only pill mill???” while cautioning them to “be mindful of everything that is put in writing.”

“These practices opened the floodgates for millions of opioid pills and other controlled substances to flow illegally out of Rite Aid’s stores,” Associate Attorney General Vanita Gupta said.

The Justice Department charged Rite Aid with violating the federal False Claims Act for allegedly submitting false prescription claims to government healthcare programs like Medicare and Medicaid. This accusation was part of a whistleblower lawsuit initiated in 2019 by two pharmacists and a pharmacy technician from Rite Aid stores in Pennsylvania, North Carolina, and West Virginia.

The opioid crisis has led to hundreds of thousands of deaths from overdoses over the past few decades, making it a major issue and a whole other topic. More than 500,000 people died from drug overdoses in the United States from 1999 to 2020, including more than 90,000 in 2020 alone, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Rite Aid has already agreed to a $30 million settlement with the state of West Virginia for similar accusations, and it’s likely that they will have to pay much more money related to this. They are not the only ones; Kroger agreed to pay $1.2 billion, and even Walgreens and CVS have agreed to multi-billion dollar settlements.

However, Rite Aid, as we’ve seen, is in no position to be paying that kind of money, adding yet another layer of complications for them.

The Scratch to the Already Bleeding Industry

After six weeks of speculation and negotiation, Rite Aid has officially filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy and has reached a tentative agreement with its largest lenders on a financial restructuring plan.

Rite Aid also announced the appointment of Jeffrey Stein, Founder of the financial advisory firm Stein Partners, as its new CEO, Chief Restructuring Officer and a member of the company’s board of directors, effective immediately.

Both store and online operations will continue as normal throughout the bankruptcy process, and a group of Rite Aid’s lenders has committed $3.45 billion in new financing to ensure the company has enough liquidity to remain in operation throughout the proceedings.

“Rite Aid has served customers and communities across our country for more than 60 years, and the important actions we are taking today will enable us to move ahead as a stronger company,” said Stein in a statement.

He continued, “With the support of our lenders, we look forward to strengthening our financial foundation, advancing our transformation initiatives and accelerating the execution of our turnaround strategy. We remain focused on serving our customers and communities, and we are grateful that they continue to choose our stores and pharmacies for their healthcare needs.”

While Rite Aid faces specific challenges, the broader retail pharmacy landscape has also endured a tough year. CVS and Walgreens witnessed staff walkouts, increased product lockdowns behind plastic barriers, and reduced store hours, reflecting industry-wide issues.

The pharmacy business has undergone substantial changes, with independent corner drugstores becoming scarce due to acquisitions or closures by larger chains like Rite Aid. Both major chains and smaller stores grapple with staffing shortages, posing challenges to maintaining profitability.

Declining reimbursement rates, coupled with high debt levels and rising interest rates, have made it less attractive for companies like Rite Aid. They now face fierce competition from supermarkets, wholesale clubs, and online pharmacies, resulting in shrinking profit margins per prescription.

Industry consolidation is a growing trend, raising concerns about limited diversity and choices in the market. This transformation may impact underserved communities, as some pharmacy chains like Rite Aid previously played a crucial role in providing access to healthcare services in these areas. The evolving pharmacy landscape has not only changed the business but also raised questions about equitable access to medicines.