Home Depot: Overhaul of Supplier Performance Management to Lead the Change

The Home Depot is the largest home improvement retailer in the United States, supplying tools, construction products, and services. The company is headquartered in unincorporated Cobb County, Georgia, with an Atlanta mailing address.

The Home Depot’s proposition was to build home-improvement superstores, larger than any of their competitors’ facilities. Investment banker Ken Langone helped Marcus and Blank to secure the necessary capital.

The first stores were huge warehouses, bigger than the competition’s locations, and had much more stock than the average hardware store. Marcus’ and Blank’s desire to offer the customer a one-stop-shop was partially inspired by their time as employees of California’s Handy Dan’s Home Improvement Center.

Prior to the 1960s and 1970s, hardware stores were small businesses that sold specialized products and customers could typically not get all of the materials for a project at one store. Also, people commonly hired professionals to complete home improvements tasks instead of doing the work themselves. Marcus and Blank hoped to change that.

One of the trademarks of The Home Depot has always been its knowledgeable staff. The associates at the store can offer advice and guidance for a number of projects, such as laying tile or operating a power tool. The company also offers clinics so customers can learn how to do their projects themselves. The Home Depot revolutionized the home improvement industry by providing consumers everything they need to complete home repair and improvement projects without hiring a professional.

By 1981, The Home Depot was a public company, which created massive growth throughout the 1990s. In 1989, The Home Depot celebrated the opening of the 100th store. The Home Depot went global. The company first opened in Canada in 1994, then moved to Mexico in 2001.

It operates many big-box format stores across the United States; all 10 provinces of Canada; and the 31 Mexican states and Mexico City. MRO company Interline Brands (now The Home Depot Pro) is also owned by The Home Depot, with 70 distribution centers across the United States.

#1. Roots in Home Depot’s Guideline: One-Stop Shopping for the “Do-It-Yourselfer”

The company was incorporated in June 1978 as a result of a corporate management shake-up by new ownership of the Handy Dan home center chain. With backing from a New York venture capital firm, Marcus and his two associates formed The Home Depot and opened the company’s first outlets in the Atlanta, Georgia, area. The concept that had helped secure financing for the project was that when the price of merchandise was marked down, sales increased while the cost of making those sales decreased. The major problem that had plagued most cut-rate retail operations, however, was poor service at the operations level, which hired unskilled, low-paid employees to keep costs down.

Marcus and his partners realized that recognizing customers’ needs was one of the most important elements in a company’s growth. They were aware that at the time do-it-yourselfers made up more than 60 percent of the building supply industry’s sales volume, but the majority of them did not have the technical knowledge or expertise to accomplish most home repair or improvement projects.

The Home Depot management team set about to solve this problem in two ways. First, they made sure that all Home Depot stores were large enough to stock at least 25,000 different items. Their competitor locations normally had room for only 10,000. The second solution was to train the sales staff in each store to help remove much of the mystery attached to home improvement projects from the minds of consumers. Marcus and his partners believed that, with the education provided by knowledgeable sales staffers, Home Depot customers would gain the confidence to take on more projects at home, coming back to Home Depot outlets to purchase what was needed and get additional advice from sales staff.

Home Depot built its sales staff from both dedicated do-it-yourselfers and professional tradespeople, hiring most employees in full-time capacities. Only 10 percent of Home Depot’s sales personnel were part-time. Whenever possible, each store had a licensed plumber and electrician on staff, and customers were urged to call the Home Depot store in their area if they had any problem or questions while they were doing their home repair or improvement projects. The company also scheduled in-store instructional workshops for its customers and in some cases brought in local contractors as teachers.

This approach paid off. By 1984 the company was operating 19 stores and reported sales of $256 million, a 118 percent increase over 1983. In 1986 Home Depot’s sales reached the $1 billion mark, and the company was operating 50 retail outlets.

#2. Home Depot’s Blueprint: An Entrepreneurial Environment to Lead the Success

Home Depot’s culture, set primarily by the charismatic Marcus (known universally among employees as Bernie), was itself a major factor in the company’s success. It was marked by an entrepreneurial high-spiritedness and a willingness to take risks; a passionate commitment to customers, colleagues, the company, and the community; and an aversion to anything that felt bureaucratic or hierarchical.

Longtime Home Depot executives recall the disdain with which store managers used to view directives from headquarters. Because everyone believed that managers should spend their time on the sales floor with customers, company paperwork often ended up buried under piles on someone’s desk, tossed in a wastebasket – or even marked with a company-supplied “B.S.” stamp and sent back to the head office. Such behavior was seen as a sign of the company’s unflinching focus on the customer. “The idea was to challenge senior managers to think about whether what they were sending out to the stores was worth store managers’ time,” says Tom Taylor, who started at Home Depot in 1983 as a parking lot attendant and today is executive vice president for merchandising and marketing.

There was a downside to this state of affairs, though. Along with arguably low-value corporate paperwork, an important store safety directive might disappear among the unread memos. And while their sense of entitled autonomy might have freed store managers to respond to local market conditions, it paradoxically made the company as a whole less flexible. A regional buyer might agree to give a supplier of, say, garden furniture, prime display space in dozens of stores in exchange for a price discount of 10% – only to have individual store managers ignore the agreement because they thought it was a bad idea. And as the chain mushroomed in size, the lack of strong career development programs was leading Home Depot to run short of the talented store managers on whom its business model depended.

All in all, the cultural characteristics that had served the retailer well when it had 200 stores started to undermine it when Lowe’s began to move into Home Depot’s big metropolitan markets from its small-town base in the mid-1990s. Individual autonomy and a focus on sales at any cost eroded profitability, particularly as stores weren’t able to benefit from economies of scale that an organization the size of Home Depot should have enjoyed.

#3. Home Depot’s Discipline: Become A Thinking-Outside-The-Box Organization to Be an Ecommerce Empire

Most employees simply could not picture the company without father figures. And if there was going to be change at the top of close-knit organization, in which promotions had nearly always come from within, no one wanted.

However, the Home Depot board had decided that a seasoned manager with the expertise to drive continued growth needed to be brought in to run what had become a giant business. The first step would be to deal with immediate problems that were not readily apparent either to employees or investors. In addition to the shortage of experienced store and district managers and the challenge from Lowe’s, which was successfully attracting women shoppers with its brighter stores and a focus on fashionable kitchen, bath, and home-furnishing products, these problems included poor inventory turns, low margins, and weak cash flow.

Nardelli laid out a three-part strategy:

- Enhance the core by improving the profitability of current and future stores in existing markets.

- Extend the business by offering related services such as tool rental and home installation of Home Depot products.

- Expand the market, both geographically and by serving new kinds of customers, such as big construction contractors.

To meet his strategy goals, Nardelli had to build an organization that understood the opportunity in, and the importance of, taking advantage of its growing scale. Some functions, such as merchandising, needed to be centralized to leverage the buying power that a giant company could wield. Previously autonomous functional, regional, and store operations needed to collaborate – merchandising needed to work more closely with store operations, for instance, to avoid conflicts like the one over the placement of garden furniture. This would be aided by making detailed performance data transparent to all the relevant parties simultaneously, so that people could base decisions on shared information. The merits of the current store environment needed to be reevaluated; its lack of signage and haphazard layout made increasingly less sense for time-pressed shoppers. And a new emphasis needed to be placed on employee training, not only to bolster the managerial ranks but also to transform orange-aproned sales associates from cheerful greeters into knowledgeable advisers who could help customers solve their home improvement problems. As Nardelli likes to say, “What so effectively got Home Depot from zero to $50 billion in sales wasn’t going to get it to the next $50 billion.”

This new strategy would require a careful renovation of Home Depot’s strong culture. Imagine the challenge: Clearly, you wanted to build on the best aspects of the existing culture, particularly people’s unusually passionate commitment to the customer and to the company. But you wanted them to rely primarily on data, not on intuition, to assess business and marketplace conditions. And you wanted people to coordinate their efforts, anathema to many in Home Depot’s entrepreneurial environment. You wanted people to be accountable for meeting companywide financial and other targets, not contemptuous of them. You wanted people to deliver not just sales growth but also other components of business performance that drive profitability.

Resistance to the changes was fierce, particularly from managers: Much of the top executive team left during Nardelli’s first year. But some saw merit in the approach and in fact tried to persuade distraught colleagues to give the new ideas a chance. Over time, attitudes slowly began to change. Some of this resulted from Nardelli’s successful efforts to get people to see for themselves why the strategy made sense. But other, more concrete tools, designed to ingrain the new culture into the organization, ultimately prompted employees to pick up a hammer and paintbrush and join the renovation project.

#4. Home Depot’s Culture: Embracing Game-Changing Chances to Stay Relevant

Most companies do not have the luxury of moving at their own rate because external factors dictate the tempo. Donovan likes to recall a comment that was frequently made at some early open meetings for employees – that the company needed to pace the changes being proposed – and Nardelli’s quick response: “Good point. Give me five minutes. I am going to go call Lowe’s and ask them to slow down for us.”

But forcing a change too quickly can backfire. Nardelli recounts his initial attempt to improve inventory turnover. “Thou shalt improve inventory turns,” he decreed. But the store managers did not have the customer data and analytic tools they needed to do that – so they simply cut back on ordering. This certainly reduced the amount of merchandise idling on the shelf. In fact, the shelves were empty.

Nardelli’s response was swift, decisive, and bold. “You put the brake on your plan,” he says. “You place $500 million in orders to reload the shelves, and then you step back and look at where your assumptions were wrong.” To reduce inventory turns in a way that worked, store managers were given and taught how to use the needed forecasting and inventory management tools, well known in the industrial sector from which Nardelli came. In describing the desired pace of change, Nardelli uses an image from NASCAR auto racing: Brake into the sharpest turns while never letting up on the throttle.

Assuming the rate of change is more or less right, how do you make change stick? How do you sustain it, integrate it into the organization, embed it in the culture? How do you keep it from being one more initiative that flares up and flames out? Home Depot’s experience suggests a number of answers.

Where possible, get people affected by a change to help define the problem and design the solution. Base your change on hard data that everyone has access to. Institutionalize the change by starting with a single project, then move to consistently apply repeatable processes that sustain it. Build accountability into such processes. Create interlocking dependencies between different parts of the organization so that they have a mutual interest in sustaining the change.

Perhaps most important, do not view transformation – even something as cataclysmic as the centralization of purchasing – as a onetime event or a point to be reached. Rather, view it as a work in progress that will constantly need to be modified. External forces require a company to constantly change, and a successful culture has a methodology that allows it to do that.

#5. Home Depot’s Digital Adoption: Business-to-Business Infrastructure Transformation

Home Depot already has a business-to-business exchange for dealings with suppliers, but the nature of the electronic exchange environment has changed significantly over the years. Fifteen years ago, says Saia, the retailer implemented Sterling Commerce as a value-added network (VAN) for the transmission of messages and documents via electronic data interchange (EDI). That process typically involves the exchange of data in batch mode, with the VAN acting as intermediary.

More recently, Home Depot realized that the technology was insufficient for its needs, particularly in light of the growth of EDI over the internet. So, this year, Home Depot is upgrading its B2B infrastructure for handling electronic exchanges with suppliers, again with the help of Sterling Commerce.

Not as the same kind of vendor, however. Dublin, Ohio-based Sterling has gone through several stages of development over the years, beginning as a provider of private, industry-specific EDI technology, according to John Stelzer, director of retail industry marketing. From there it moved into more standardized EDI formats, growing as a classic VAN, then as a provider of software for translating and reformatting data according to the technology of various trading partners. More recently, Sterling has developed the Gentran Integration Suite (GIS), a hosted platform for connectivity and data translation that allows for a true B2B electronic exchange, regardless of the technological sophistication of its many users.

To Stelzer, a modern-day exchange is not just about getting information from one party to another. “It’s about what is done with the information.” Today’s systems must be able to execute special processing depending on the type of product and whether it is sourced domestically or internationally. The challenge facing Home Depot, as with any major retailer, lies in building a system that allows for automated and highly integrated links with all suppliers, and is flexible enough to adjust for the unique characteristics of each, Stelzer says.

Such a tool can also be used to drive supplier compliance, he says. One component of GIS, dubbed Visibility Manager, monitors a supplier’s track record in transmitting and receiving all necessary documents, including purchase orders, advance shipment notices and invoices, in a timely manner. A system of exception-based alerts flags any supplier who is falling short in that regard.

In the near future, Stelzer says, the software will be able to grade the accuracy of each message, a critical part of any supplier-compliance program. “Reconciliation across document content is clearly the next step,” he says.

A key feature of modern B2B exchange software is its accessibility by all levels of an organization. No longer is the content intended only for IT staff. Individuals from sales, marketing, logistics and customer service can make use of information about supplier performance, including the real-time status of orders and shipments. Sterling’s GIS has had that capability for about a year, Stelzer says.

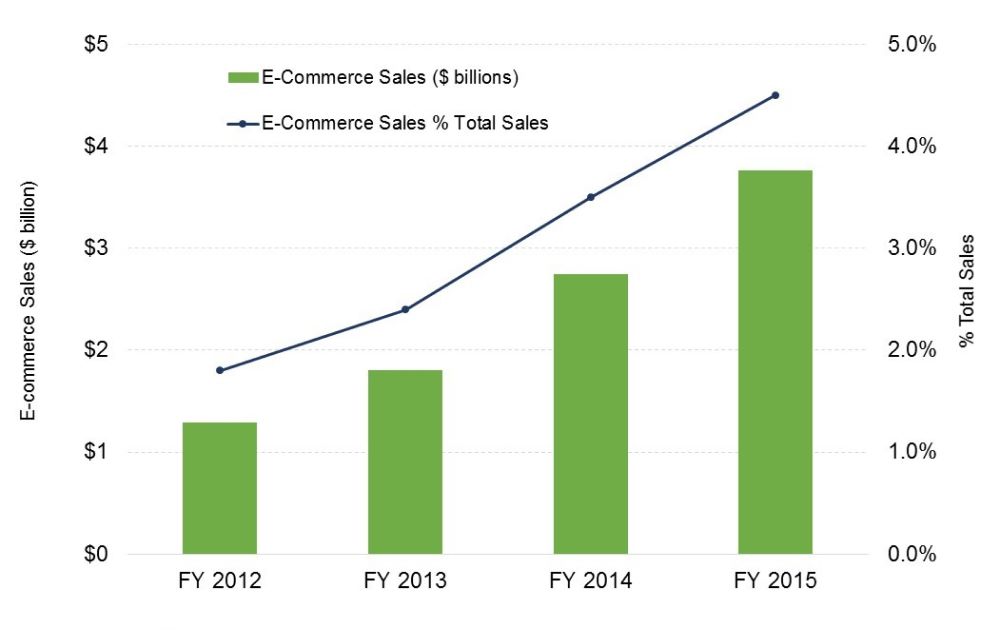

For Krishna and Vemana, what they call Home Depot’s “Tech 2.0” era started with the 2008 hiring of Matt Carey, a former Ebay CTO, as Home Depot’s chief information officer. Two years later, as part of a regular strategy review, company officials decided to dive even deeper into digital waters.

“That is when we said, hey, customers are leveraging tools in technology, so how do we pivot?” Krishna said. “That is when we decided to invest in digital technologies.” That spend also included acquiring startups. Both Black Locus and Redbeacon joined Home Depot in 2012 with Blinds.com joining in 2014.

Austin’s Black Locus helps Home Depot keep its customer promise of Every Day Low Price guarantees. “We do not do trick plays with coupons and price changes every two minutes like some others. That is not our business,” Krishna said. “Customers get the best price every day in our physical and digital stores. “But we want to know, learn, and do better for our customer every single day.”

Redbeacon, rebranded this year as ProReferral, helps cement Home Depot’s relationship with home services professionals. Customers can search and compare plumbers, carpenters and other specialists that “come with a certain level of authenticity and credibility that comes with Home Depot,” Krishna said. “If we can help out professional customers, that’s going to help the rest of our customers.”

Much of the software engineering is done in-house, and by most metrics Home Depot’s technology team feels like a West Coast software company

This kind of large-scale software engineering is needed to deliver exceptional retail experiences for customers and internal associates. “Getting from a customer’s desire for product or service to ‘wow-ing’ the customer takes a lot of technology in the interconnected world. If it is a core competency of ours, we will build it ourselves. We are fortunate to have a phenomenal team that wakes up every morning to make Home Depot better for our customers,” Naveen said.

#6. Home Depot Sales Amid COVID-19 Crisis: Surging on Renovation Breakthrough

Home Depot reported sales growth that was more than double the already brisk rate analysts had been expecting, but rising expenses meant flat margins in an otherwise standout quarter.

Same-store sales rose 23.4%, sharply beating the estimate for an 11.4% gain from Consensus Metrix. Revenue of $38.1 billion also surpassed expectations. The gain was driven by both higher average customer checks and more transactions, meaning more shoppers bought from Home Depot in the quarter and they spent more every time they came in. Comparable sales in August are at similar levels to the past quarter, executives said on a call with analysts.

But even though Americans have been opening their wallets on home improvement during the pandemic, the retailer has also faced higher costs to serve those customers. Selling, general and administrative costs jumped 26% in the quarter, with Morgan Stanley’s Simeon Gutman noting the company is spending more than anticipated on virus-related costs and benefits.

Like many companies during the pandemic, Home Depot suspended its full-year forecast in May due to widespread uncertainty around Covid-19 and its impact on the broader economy.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic evolved, we anchored to the core values of our company by focusing on two key priorities: working to ensure the safety and well-being of our associates and customers, and providing our customers and communities with essential products,” said Craig Menear, chairman, CEO and president. “We took early and decisive action to intentionally limit customer traffic in our stores, which we believe had a significant impact in many markets.

“Even with these actions,” he said, “the robust and flexible interconnected infrastructure that we have invested in for over a decade allowed us to quickly adapt to changing customer preferences and achieve strong sales performance in the quarter.”

Home Depot, long viewed as a proxy for the U.S. housing market, benefitted as mortgage rates are at a record low, driving demand for new homes and keeping the Atlanta-based retailer’s goods in high demand. U.S. home construction starts increased in July by more than forecast, according to data released Tuesday. Home Depot said its business serving do-it-yourself customers is growing faster than its pro-business, aimed at contractors. Home Depot shares fell 1.1% to $285.11 at 11:55 a.m. in New York. The stock had advanced 32% this year through Monday, far outperforming the S&P 500 Index.