Whole Foods: From A Hippie Natural Food Store to Amazon’s $13.7B Grocery Weapon

From a small natural foods store in the hippie haven of Austin, Texas, Whole Foods has undoubtedly grown into an admirable retail juggernaut within the health and wellness arena, impressing the market with its sales performance and growth while other large grocers struggle and face uncertain futures. Claiming to be “a place for you to shop where value is inseparable from values,” Whole Foods has continuously propelled its success as “America’s Healthiest Grocery Store.”

Notwithstanding that, the growth trajectory of a behemoth is rarely a straightforward journey, especially in the case of Whole Foods. How did the retailer manage to rise beyond its humble beginnings as well as bounce back with a vengeance during the uncertainties? Which pitfalls did the company navigate against along the course? Let’s read on to uncover!

1980 – 2002: Ambitious Acquisitions & Organic Growth

The Early Years: SaferWay Natural Foods

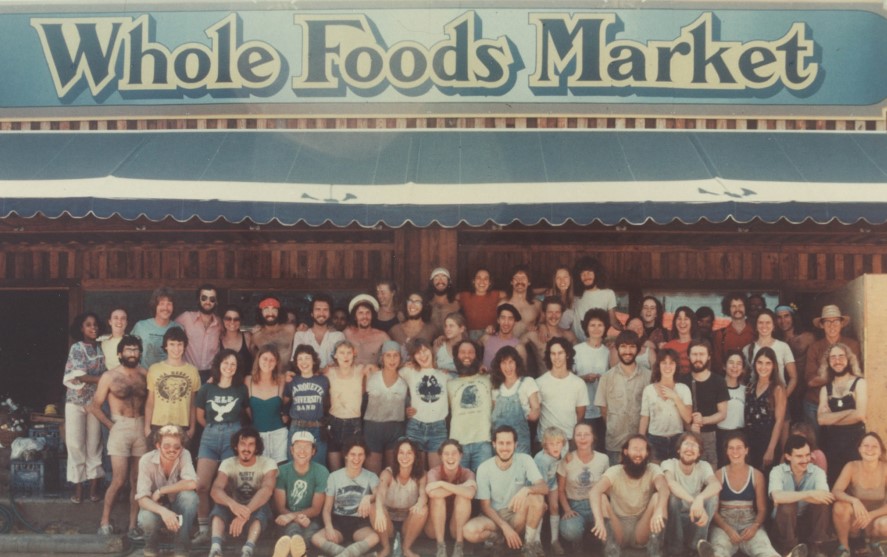

Given that the Whole Foods story “officially” started in 1980, John Mackey and Renee Lawson Hardy opened SaferWay Natural Foods – the 2,000-square-foot store based in Austin and the very first branch of what would later become Whole Foods—two years earlier, in 1978.

By that time, the commercial food retail landscape had been witnessing the immense transformation. Fostered by two decades of meteoric post-war economic growth, supermarkets had become a familiar sight across the nation. As a result, shoppers had become accustomed to the growing range of frozen and pre-packaged convenience foods that the supermarkets brought with them. Yet, not all consumers embraced the ease and convenience promised by the expanding supermarket chains of the day. After experiencing more than 20 years of growth driven by fears of nuclear conflict during the Cold War, canned goods were gradually waning in popularity. In fact, several consumers longed for fresh, handpicked produce grown by local farmers.

And it was exactly such a desire for authentic, locally grown produce that Mackey and Lawson Hardy capitalized on when they opened their SaferWay Natural Foods store, a tongue-in-cheek play on the Safeway supermarket brand. The business started with a dream … and a loan: the couple borrowed around $45,000 from friends and family to hit the ground running. Then, in 1980, SaferWay Natural Foods merged with another local food store, Clarksville Natural Grocery, from which Whole Foods Market was born.

Whole Foods Market: Ground-Breaking Yet Rough Beginning

Beyond just running a grocery store, the couple’s ambition was to reshape the way people perceived food as well as its role in the community. Instead of sourcing pre-packaged fruits and vegetables laden with commercial pesticides from industrialized farms, they partnered with local farmers from the Austin area. The store’s “business model” was quite season-based in which the store rotated its stock frequently, and availability was determined by the time of year.

Nowadays, this might seem like a shallow attempt to co-opt an idealized sense of authenticity that is largely lacking in commercial food production. Nevertheless, for Mackey and Lawson Hardy, it was the core identity of their business – and exactly what would drive much of Whole Foods’s growth over the next two decades.

Indeed, every single thing about Whole Foods was designed to cultivate and reinforce this sense of authenticity: the store’s signage was written on chalkboards; farmers showed up at the store personally to deliver that week’s crop, the beds of their battered pickup trucks crammed with beets, carrots, heirloom tomatoes, and dozens of other veggies. Everything just delivered a genuine experience – an alternative to the mainstream supermarkets that Whole Foods Market’s laid-back customers avoided.

Beyond a shadow of a doubt, no business success story would be complete without a big and challenging incident somewhere in the middle. Yet, whereas every growing business is subject to early-day obstacles, not all companies face the kind of disaster that threatens to destroy the entire business before it’s even gotten off the ground. That was exactly what the Austin store struggled against less than a year after its opening in 1980.

To be more precise, on Memorial Day, 1981, the worst flood in a generation wreaked havoc on much of the city of Austin and caused catastrophic damages. The store itself was submerged under eight feet of standing water. As for Whole Foods Market, the entirety of the store’s inventory was ruined. It would take days to get the power back up. Total damages exceeded $400,000—and more importantly, the store didn’t even have insurance.

It seemed Mackey and Lawson Hardy’s dream was over before it even began!

Yet, fortunately, in response to the flood, community members rallied to save the store. Neighbors helped to clean up the store whilst the market’s creditors and vendors gave Mackey and Lawson Hardy some much-needed breathing room. Incredibly, Whole Foods Market reopened just 28 days after the disastrous flood.

Recalling this experience, John Mackey shared, “Our Team Members grew closer together, our commitment to our customers was greatly deepened, and we came to understand that we were actually making an important difference in people’s lives. If all of our stakeholders hadn’t cared so much about our company then and come together in support, Whole Foods Market would have ceased to exist.”

While the community response to the flood became a crucial milestone of the Whole Foods success story, it was striking and remarkable for another reason: this was a testament that Whole Foods Market’s vision was working. Rather than being just another branch of another supermarket, the natural retailer was a locally-owned market that had deep ties to the community – such a bond strong was enough to survive the worst flood to hit Austin in 70 years. In less than a year, Whole Foods Market had become a critical part of the fabric of the community—exactly what John Mackey and Lawson Hardy set out to nurture.

The First Steps of Whole Foods’s Expansion Efforts

Weathering through the flood, Whole Foods Market became stronger than ever. Rather than turning to their family and friends for financial help, they counted on themselves as well as bootstrapped their expansion plans. That’s exactly what they did in 1984 when Whole Foods Market opened its second location in Houston, Texas. Just one year following, Whole Foods Market had more than 600 employees. Soon after opening its doors in Houston, Whole Foods Market launched a third location in Dallas, Texas.

Until 1988, the couple were eager to expand their vision beyond the Lone Star State. In an effort to realize their ambitious growth plans, John Mackey began approaching venture capitalists for investment funding. Yet, one VC after another turned him down. They just couldn’t see the vast potential market that Mackey and Lawson Hardy had identified as a meaningful alternative to the processed frozen foods favored by mainstream supermarkets of the time.

1988 Onwards: Beyond the Lone Star State

By 1988, Whole Foods Market expanded outside of Texas with the acquisition of the similarly named Whole Foods Company of New Orleans. Whole Foods’s early growth came largely from mergers and acquisitions.

In 1992, once having operated 12 stores in Texas, California, North Carolina, and Louisiana, Whole Foods went public, going from “Austin to Wall Street”. As stated on the prospectus, “a significant segment of the population now attributes added value to high-quality natural food.” “These gleaming new supermarkets — 13,000 to 27,000 square feet of floor space — bear about as much resemblance to the grungy, 1960s fern-bedecked natural food co-op, with its shriveled produce and flour stored in trash cans, as McDonald’s does to Lutèce,” wrote Marian Burros, a food reporter at The New York Times. Then later that year, the company expanded into the Northeast with the purchase of the Boston-based supermarket chain Bread and Circus.

1996 marked a year when Whole Food grew from a hippie to hip capitalist. The retailer acquired Fresh Fields, a Maryland-based chain with 22 stores. At that time, John Mackey’s natural foods empire consisted of 70 stores in 16 states. While still small compared to traditional supermarket chains, the natural and organic foods company grew by more than 20% on an annual basis. The next year, revenue surpassed $1 billion.

2002–2012: Spreading “Conscious Capitalism”

The Advent Of “Conscious Capitalism”

From a hippie natural food store in 1980, Whole Foods became a retail juggernaut, passing the mark of $2.7 billion in fiscal sales by 2002. Also in this year, the company expanded internationally for the first time with its first Canadian store in Toronto. This marked the next stage in Whole Foods’s growth – The evolution of its original unique value proposition into the broader, more clearly defined corporate mission of “conscious capitalism.”

In the early 2000s, more sustainable approaches to consumerism increasingly gained ground among mainstream consumers. However, whereas consumers were gradually shifting toward more ethical, sustainable ways of shopping, the movement itself lacked a name—something that John Mackey was keen to capitalize on. That’s when the idea of “conscious capitalism” was born. Regarding this, John Mackey commented that “One of the things that have held back natural foods for a long time is that most of the other people in this business never really embraced capitalism the way I did.”

Whole Foods: Not Only A Grocery Store but Also A Lifestyle Coach

As Whole Foods continued to “swallow” entire natural grocery chains, the Austin-based natural food giant began to direct its efforts towards how its original unique value proposition could be expanded beyond how it sourced produce. Not only were Whole Foods stores getting bigger, they were also becoming much greener. For instance, the retailer installed photovoltaic panels on the roof of its store in Berkeley, California, making Whole Foods the first national food retailer in the U.S. to use solar power. Soon then, the company became the first certified organic grocer in the country and began supplying many of its stores in the mid-Atlantic region with wind power. Later, in 2004, Whole Foods earned Green Power Leadership Award by the Environmental Protection Agency for its commitment to sustainable energy, an accolade the chain retained for four consecutive years.

Whole Foods’s commitments to ethical business practices and environmental sustainability weren’t just logical extensions of the company’s original unique value proposition. Rather, they were a crucial element of the Whole Foods brand. More than anyone, John Mackey knew that a plethora of consumers embraced the authenticity of locally grown produce and the convenience of modern supermarkets. He also knew that cultivating his company’s vision and brand values would further differentiate Whole Foods from an army of emerging competitors.

Not only about good food, Whole Foods did also care about saving the rain forests, protecting the oceans, and reducing carbon footprints. And again, rather than just another chain of supermarkets, the retailer behemoth aimed to be the supermarket for socially and environmentally responsible consumers. Indeed, shopping at Whole Foods wasn’t about choosing a grocery store – it was about adopting a lifestyle.

The Pitfall of Being Too Ambitious

Whilst the retail behemoth had been enthusiastically acquiring organic grocery stores in an effort to accelerate its growth and access into ready-made markets in affluent urban areas, many of the qualities of Whole Foods’s growing stores stood decidedly at odds with the company’s original mission.

Given that Whole Foods Market still sold organic produce grown by local farmers, its stores had become apparently more indulgent. Particularly, some of the chain’s larger stores had introduced in-store restaurants, brick-oven pizzerias, gelato counters, and even luxury spas to attract the chain’s target demographic of young, affluent, socially conscious shoppers. Having started as a grocery store for hippies, Whole Foods Market became a grocery store for yuppies.

Nonetheless, despite the chain’s burgeoning identity crisis, Whole Foods Market managed to sustain its robust growth. Beyond a grocery chain, the retailer had also grown as a brand. Undoubtedly, Whole Foods’s mission to offer ethically sourced organic groceries was resonating strongly with consumers, which in turn fueled further growth and strengthened Whole Foods’s position as an influential retail brand in a rapidly growing vertical. Then, what Whole Foods should do was deliver its heartfelt message to an entirely new generation of conscious consumers.

“This company is a mission-based company. This company started to change the world by bringing healthier food to the world. It’s not about the money, it’s about the impact, and this company is back on track as a result of those experiences.”

– Walter Robb, Co-CEO of Whole Foods Market

2012–Present: Downward Growth of The Organic Empire & Savvy $13.7-Billion Acquisition by Amazon

The Historic Year of 2012 …

2012 emerged as the best year in the retail juggernaut’s 32-year history when Whole Foods was a household name across much of North America with staggeringly 335 Whole Foods stores across the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Having enjoyed 11 consecutive quarters of growth, the company had its net sales stand at $11.7B, the equivalent of $932 in revenue for every square foot of store space. When it came to Whole Foods’s share price, the figure had reached an all-time high of $101 per share.

Nonetheless, whereas Whole Foods experienced handsome success in 2012, that year also marked the point at which the retailer’s fortunes began to change for the worse. Though Whole Foods Market became a strongly-established brand alongside its physical expansion across the U.S., negative attention arose. Given that Whole Foods had cultivated a reputation for the quality of its products, the chain was arguably well-known for its high prices, which resulted in the store’s nickname: Whole Paycheck.

As regards Whole Foods Market’s organizational expertise and resources, Whole Foods had fallen victim to the common start-up pitfall: the company had been focusing almost exclusively on growth while neglecting the other elements of its business.

To “add fuel to the fire”, although Whole Foods had adopted several practices to advance the cause of organic produce than any other retailer, it had inadvertently triggered an army of competitors who saw organic as the dramatic shift in consumer preferences it was. In fact, virtually every single supermarket chain and wholesaler was pushing organic produce aggressively and that – as a result – substantially drove down costs. Consumers not only had more choices than ever before—significantly weakening Whole Foods’s unique value proposition—but also now expected lower prices, thanks to intensifying competition.

Although Whole Foods’s issues explicitly came to light in 2012, the heightened competition was not a recent development. From several analysts’ standpoints, Whole Foods had been susceptible to the challenge of newer entrants within the organic produce sphere since at least 2006. However, the retail giant believed it could outpace its emerging competition by opening more stores – such shortsightedness and the chain’s hubris as the nation’s leading organic grocer were both in Whole Foods’s decline. Beyond any doubt, whereas it was Whole Foods that inspired and revolutionized the market for natural and organic produce, this emerged as the victim of its own success.

.. And the Following Struggling Years

Though the chain struggled to navigate against fierce competition, Whole Foods invested non-stop efforts in the environmental and social causes, which markedly had fueled its rise to dominance in the 2000s. Yet, although Whole Foods had once been seen as a leader in the food retail sector, the chain was now playing catch-up, being reactively protective of its dwindling market share.

Despite many tactics employed to sparkle innovation and appeal to new customers, one of the company’s biggest mistakes was failing to recognize just how glaring a vulnerability its pricing really was and what potential impact this would ultimately have on the Whole Foods brand.

Needless to say, Whole Foods’s once-unique value proposition had been co-opted by mainstream grocery stores and supermarkets – typically Costco and Walmart, right down to the rustic chalkboard signage. Beyond the lavish but ultimately frivolous in-store amenities available at some locations, there was virtually nothing to differentiate Whole Foods stores from any other supermarket in a truly meaningful way.

And it didn’t take long to manifest that situation in Whole Foods’s net sales. In particular, between 2005 and 2015, sales of organic food in the U.S. increased by staggering 209% to a record-breaking $43B in 2015 alone. Yet, that same year, Whole Foods reported a steep decline in comparable store sales for the first time since 2009. Actually, the company’s share value plummeted by 40%.

Commenting on this, John Mackey stated, “Increased competition has forced us to look more closely at our pricing strategy and do a better job of conveying our value offerings—we look at it as a good thing because it forces us to do better. Nobody in the industry can match the level of quality standards we maintain across all departments, so it’s about balancing the quality with value to ensure there’s something for everyone in our stores.”

Unfortunately, by the time Whole Foods realized the company’s reputation for high prices was its Achilles heel, it was too late. Having tried and failed to shift the public’s focus away from Whole Foods’s pricing – especially the attempt to offset its negative reputation by pivoting away from its premium lines in favor of its 365 Everyday Value private-label brand, the retailer relented and began lowering prices across the board. However, even such a begrudging measure did not do wonder for Whole Foods’s troubles.

In early 2017, after six consecutive quarters of declining sales, the retailer closed 09 stores across the U.S., which was the first time the company had actively downsized since 2008.

Amazon with an Eye on Whole Foods’s Acquisition

In spite of Whole Foods’s continued efforts to demonstrate its commitment to ethically sourced food, the retailer was out of ideas. Its sales continued to fall, and amid growing speculation of a forthcoming sale by several economic analysts, Amazon announced its acquisition of Whole Foods in a deal valued at US$13.7 billion, including debt.

“Millions of people love Whole Foods Market because they offer the best natural and organic foods, and they make it fun to eat healthy,” stated Jeff Bezos, Amazon founder and CEO, in a press release announcing the acquisition. “Whole Foods Market has been satisfying, delighting and nourishing customers for nearly four decades – they’re doing an amazing job and we want that to continue.”

Such an acquisition decision might be a savvy business decision for both parties — Amazon has been dabbling in groceries and Whole Foods needs to better compete with the burgeoning natural foods market it helped launch. Yet, the founding ethos of those two businesses are as different as a “chocolate pop tart and organic oatmeal.” The Seattle-based tech giant of Amazon is the result of Jeff Bezos’ obsession with the efficiency and scalability of the Internet; Whole Foods, in the meanwhile, is an idealistic attempt to reshape the way people eat, making them healthier, while promoting sustainable, fairly harvested foods and ethically sourced meats.

Shortly after the acquisition news broke, there existed considerable concerns amongst analysts as to whether Amazon was a solid ideological fit for such a socially and environmentally conscious retailer as Whole Foods. Yet, this line of thinking entirely misses the point of the acquisition.

Obviously, Amazon’s acquisition of Whole Foods wasn’t about ideology. Rather, it was about Amazon’s ambition for immediate entry into an intensely competitive landscape. On Amazon’s side, the timing couldn’t have been better: Whole Foods was sinking fast, with nowhere to turn, and struggling with growing hostility from an already belligerent board of activist investors.

Besides, the near-overnight access into the flourishing food retail sphere wasn’t the only reason Whole Foods was such a wise investment for Amazon. To be more precise, the chain’s predominantly urban and upper-class suburban locations are just ideal for Amazon’s already extensive nationwide distribution network. Instead of custom-building brand-new distribution centers for its Fresh grocery delivery business, what Amazon has to do is just retrofit its Whole Foods locations.

The Bottom Line

Beyond any doubt, Whole Foods Market has had quite the ride. Over the course of 39 years, CEO and co-founder John Mackey has taken Whole Foods from a hippie natural foods store to Amazon’s $13.7 billion grocery weapon. Yet, whilst Whole Foods emerged as Amazon’s biggest subsidiary uncertain, its future as a brand is still uncertain. In fact, to what extent Whole Foods remains a distinct corporate entity from its parent company—and whether the chain will retain its strong commitment to environmental and social causes—remains to be seen.