Saint Louis: How to Catch Big Fish in the “Gateway City” for Young Entrepreneurs?

“We love the Cardinals, we love the Blues, and we love our startups.”

That is how Cliff Holekamp, co-founder and managing director of Missouri’s most active venture capital firm, Cultivation Capital, described St. Louis, a.k.a the “Gateway City.”

And things are looking up, according to the St. Louis Regional Chamber’s senior research director, Tim Alexander. “Greater St. Louis has made great progress in building the amount of VC investments in area companies,” he said. “The total for the last five years of $1.9 billion is double that of the previous five-year period.”

The Arch Grants Global Startup Competition awards totally $1 million in equity-free grants annually to 20 startups of a diverse range of backgrounds, and it’s helped put St. Louis on the map for ambitious young businesses all across the country.

Playing the Long Game of Economic Development

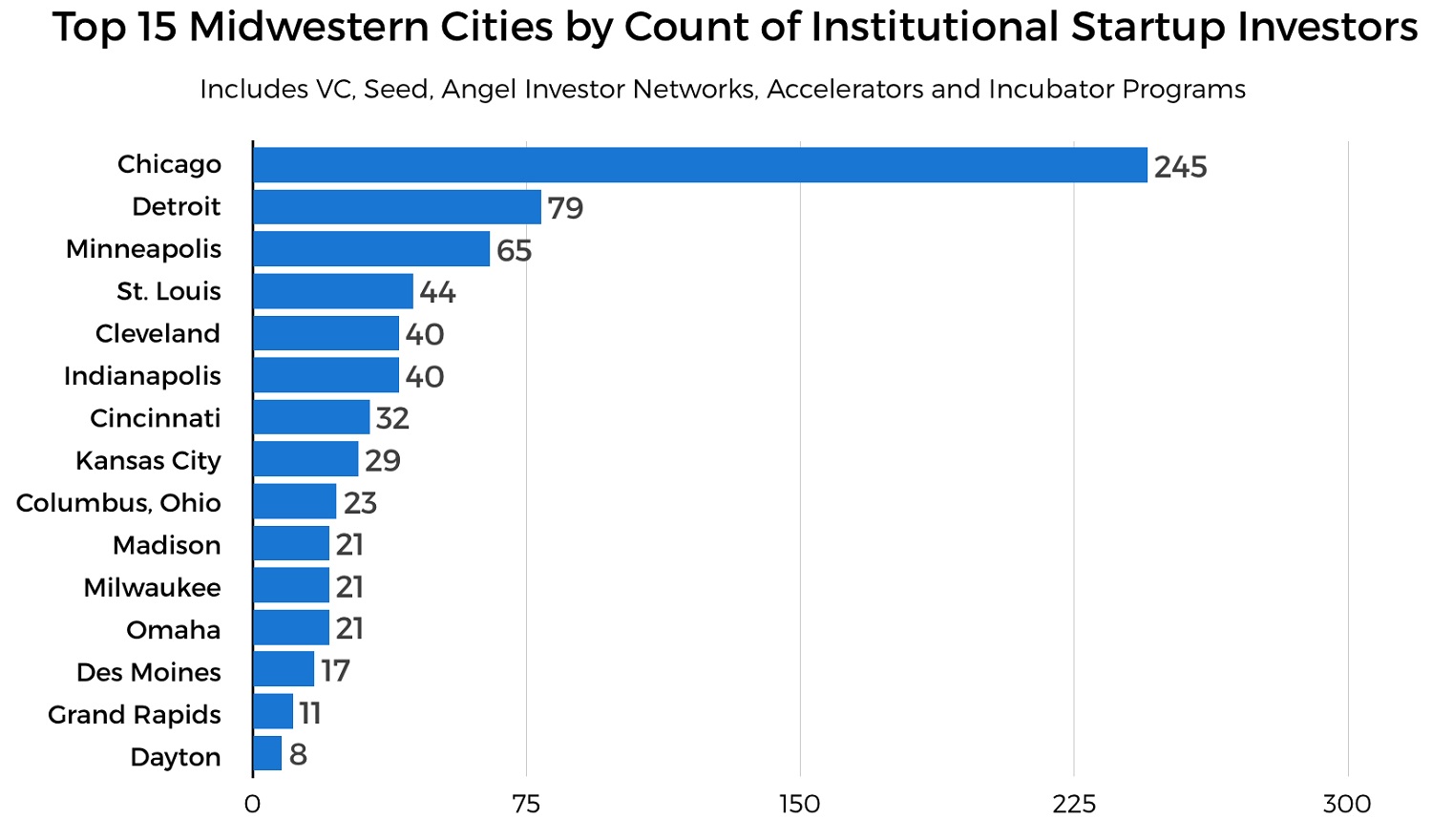

Funding Scene

St. Louis is home to 19 Fortune1000 companies, but that doesn’t mean it has the same ruthless attitude towards competition that many experiences on the coasts.

The city’s biggest businesses don’t just talk about the benefits of welcoming and working with startups, but also back it up by getting actively involved in programs and organizations like Arch Grants, as well as meeting, mentoring, and yes, doing real business with startups like Longneck & Thunderfoot (L&T) and Less Annoying CRM (LACRM).

Just take it from one of the biggest players in the city: “As a company that was founded by two St. Louis entrepreneurs, innovation is in our DNA,” says Patrick J. Sly, Former Executive Vice President at Emerson Electric. “Emerson is a strong advocate of enabling the growth of new ideas. “

In places like New York, trying to get your foot in the door with major companies can feel pretty futile, with so many startups fighting for the attention of a few big partners. But that’s not the case in the Gateway City, where we found big companies eager to work with the entrepreneurs who were most clearly dedicated to doing quality work, not necessarily those with the biggest crowd of angel investors behind them.

Arch Grants is another important factor in St. Louis’ startup scene. Executive Director Emily Lohse-Busch shared that this nonprofit is mainly a vehicle to attract and retain talent to build the future economy in the St. Louis region.

And yet, even in a smaller city like St. Louis, it’s not likely that you’ll just run into a future client on the street: someone has to introduce the big guys to startups like us. Luckily, that’s exactly what Arch Grants does, serving as a connector between its recipients and native corporate partners.

Overall, the organization aims to increase economic development in the area via innovation and entrepreneurship by bringing companies to the region and retaining early-stage companies.

Regional Advantages

St. Louis provides a popular launch for startups because of its low cost of living, access to funding, large academic research institutions and the aforementioned framework that is supportive of innovation.

The area has also been named a top city for young entrepreneurs, the happiest city in America, and boasts over 30 four-year colleges and universities, ripe with eager talent graduating each year.

“Some of these advantages,” the Chamber’s Menietti added, “stem from our outstanding academic institutions, nonprofits and innovation districts: Washington University, Saint Louis University, Danforth Plant and Life Science Center, 39 North, Cortex, T-REX, Arch Grants and LaunchCode–to name a few.”

Noted Cultivation Capital’s Holekamp, “What makes the St. Louis startup community special is the interconnectivity and support our entrepreneurs receive from all parts of the greater St. Louis community. Startup news is well covered in the local press, and our entrepreneurs are given a platform here to make their mark. A lot of cities are entrepreneur-friendly, but I know of no city who celebrates entrepreneurs the way St. Louis does.

“We have strong and well-supported co-working clusters,” he added. “T-REX for software and tech, Cortex for life sciences and corporate innovation, and 39 North for AgTech.”

Key Differences

In some ways, St. Louis is not unique. What we call “startup fever” has swept the country over the last several years.

Pittsburgh, for example, has been celebrated for its entrepreneurial renaissance, with recognition from various “best places to start” rankings, and an increase in venture funding, new incubators, and state programs. But this activity has yet to translate into entrepreneurial outcomes. In 2014 and 2015, Pittsburgh ranked last among large metro areas on the Kauffman Index, with the lowest rate of new entrepreneurial entry, the second-lowest startup density, and even one of the lowest rates of “opportunity” entrepreneurship. A similar story might be told of cities such as Milwaukee, Cincinnati, and Philadelphia.

What, then, is St. Louis doing differently that might explain its relative success?

In an article in the journal Innovations, Ken Harrington, who led the Skandalaris Center for over a decade and has been closely involved in the St. Louis startup scene, argues for “connectivity.”

In the past, St. Louis was not without entrepreneurial energy, according to Harrington, but it existed in disconnected pockets. This stymied the formation of an “entrepreneurial genealogy” that occurs when successful entrepreneurs from one generation become the next generation’s mentors and investors. This genealogy is a distinguishing characteristic of places such as Silicon Valley.

A metro area without this genealogy needs to create it by bringing together the disconnected pockets. It’s faddish in economic development circles today to talk about collisions. If you create lots of bars and coffee shops and parks, serendipitous unexpected connections will occur: The strategy is premised on people running into each other.

But that’s not what happened in St. Louis. Instead, organizations such as ITEN, the Skandalaris Center and Arch Grants came into being and intentionally and deliberately built connections and networks.

An example of how this connectivity can work is RoverTown, a startup that provides student discounts through a mobile app. After receiving an Arch Grant in 2013, the company moved to St. Louis from Carbondale, Ill. It relocated to T-Rex, a nonprofit co-working space downtown, went through an accelerator program called Capital Innovators and received a follow-on Arch Grant.

It then took part in another program run by ITEN called Mock Angel, which prepares entrepreneurs to make their pitches to equity investors, and secured nearly a million dollars in funding last year. In 2014 it was named the fastest-growing tech startup in St. Louis. RoverTown is not small-time — they have a satellite office in Chicago, and two VPs of GrubHub are on the board. They are in St. Louis by choice.

RoverTown’s experience also illustrates another side of St. Louis connectivity. One of its investors is Tom Hillman, a serial entrepreneur who formerly owned Answers.com, a leading IT firm based in St. Louis. Hillman has become a central figure in St. Louis entrepreneurship and philanthropy and embodies the new entrepreneurial genealogy that has developed in the region.

How to Catch the Next Big Fish?

While there’s plenty that sets St. Louis apart, there are some things every city in the country has in common: in an era full of instant success stories emerging from Silicon Valley, everyone wants to play host to the next Google or Facebook.

Still skeptical that a huge game-changer could grow out of a smaller city like St. Louis? You might be surprised to hear that it’s already happened: thirty years ago, when the biggest prescription benefit provider in the country, Express Scripts, was founded right here.

In a city that has seen huge successes like Express, Emerson, and Anheuser-Busch provide a boost to its local economy, everyone is invested in fostering the growth of St. Louis’s burgeoning business community. The goal? Attract a “next big thing” company. “It helps everyone in the city if St. Louis is home to the next Google,” King says. “A rising tide lifts all boats.”

I think the path to that next big thing runs through Arch Grants. In the year since we received a Grant, we’ve seen how committed the organization is not only to boosting St. Louis businesses in general, but supporting diversity in it as well — 74% of Arch Grants companies still in operation are led or co-led by a woman, person of color, immigrant, or veteran.

And for founders familiar with the challenges of scaling a business, Executive Director Ben Burke explains the unique opportunity the grant poses for startups in moments of transition: “Since Arch Grants offers equity-free cash, we’re invested in helping entrepreneurs build a solid foundation for their company while creating space for them to take necessary risks. It’s essential that these young companies can pivot as needed, so we give them the support and room to grow.”

Put it all together, and I don’t think it’s hard to see why I would encourage any founder of a young company to consider applying for an equity-free grant in the upcoming Global Startup Competition.

Interacting with the St. Louis Ecosystem

In terms of scale, St. Louis doesn’t come anywhere near Silicon Valley. But its size is actually one of the main things it has going for it.

“St. Louis is small enough that you can get to know all the players, they’ll take your calls, you can meet with them, and it makes for a really rich environment,” says Doug Villhard, academic director of entrepreneurship at Olin Business School at Washington University in St. Louis.

For his MBA students, he emphasizes the importance of going out and getting practical experience working for or running a startup.

“The opportunity to learn is one thing, but to be able to practice is another,” he adds. “St. Louis’ ecosystem really lets you get out there and interact with it.”

Olin MBA students have dozens of accelerators, incubators, and startups at their disposal. The curriculum emphasizes an experiential learning approach to ensure students can get to know these different organizations in the ecosystem and learn from them.

Students can participate in a consulting project with a local early-stage startup through Olin’s Center for Experiential Learning (CEL). In the school’s CELect (CEL Entrepreneurship Consulting Team) program, students work alongside a founder through the fledgling stages of their business, gathering information and ground-based research to help drive their business plan.

CELect has a great appeal for startups, too. They have the opportunity to get input and business advice from top MBA students.

There’s also the Metrics Clinic course—an eight-week program that partners students with startups looking for data-driven consulting. This exposes students to how data is transforming the experience of entrepreneurs.

This hands-on approach centers on a belief that if students are learning about entrepreneurship, they should be learning from entrepreneurs.

“If you want to be a brain surgeon, students prefer to be taught by an actual brain surgeon,” Doug says, “With entrepreneurship, there’s tremendous theory to be taught by academics, but there’s something relatable about being able to give examples of actual experience.”

Setting Up a Business in St. Louis

St. Louis’ thriving ecosystem hasn’t always been there. Doug is often quick to remind his students how the landscape has changed during the time since he’s been based there.

“I tell them what I had to go through, leases I had to break, introductions I had to bang on doors to make, investments that I needed to make both in St. Louis and other startup cities,” he recalls, “Students are really getting benefits from those who have worked really hard to create this ecosystem.”

One of the main shifts is the increasing opportunity MBA students have to launch their own business, either during or after their degree. In this way, Olin is one of the big contributors to the ecosystem, both in terms of businesses and workforce.

Olin has seen some exciting startups spring out and establish themselves in St. Louis in the past few years. Current MBA student Byron Porter has launched his business, HUM Industrial Technology—a device, powered by machine learning software, that can detect when train parts need mending or replacement.

The desire to address problems through entrepreneurship and innovation is deeply rooted in the school’s ethos.

“The first thing students learn is to fall in love with the problem, and then we teach them how to do something about it,” he insists.

The startup opportunities in St. Louis aren’t focused in one particular area. The city has three main innovation districts: 39 North, based mostly around plant science and agriculture; Cortex, focused on the biomedical industry; and Washington Avenue, the downtown district where most tech firms are based.

Bang in the center of all this entrepreneurship and innovation is WashU and Olin Business School. “WashU students are highly desired in this ecosystem. They’re kind of the big dogs around town,” Doug says.

They have, Doug believes, a mindset that makes them stand out not just to new ventures but to big corporations as well.

“Entrepreneurship isn’t just a career. It’s a mindset. The mindset of looking for problems—figuring out how to solve them—is helpful in all careers.”

Working Together

Multiple forces work together to both maintain and increase the startup capacity of St. Louis and the surrounding area. One of these forces, the Chamber, has devoted a key role to the goal.

Enter Matt Menietti, the Chamber’s director of innovation and entrepreneurship. He uses several pillars to increase capacity for the city’s high-growth startup ecosystem. These include:

- Connecting, aligning, and celebrating regional startup leaders.

- Increasing the number of quality relationships among entrepreneurs.

- Reducing the amount of friction new participants to the startup ecosystem encounter when launching new companies (wayfinding, storytelling, etc.).

- Co-developing innovation-forward and entrepreneur-friendly policies across the St. Louis region.

“We play a support role and try to find ways that we can best champion and accelerate the excellent work our region’s accelerators, incubators, universities, funders and community leaders are already doing,” Menietti said.

Another crucial player in St. Louis’ startup scene can be found in Phyllis Ellison. Ellison is vice president of Partnerships & Program Development at the Cortex Innovation Community.

The Cortex Innovation Community is the largest innovation center in the St. Louis region. It is a 200-acre hub for building connections for startups, corporations, academic partners, and the broader community, according to Ellison.

In fact, St. Louis has a wealth of entrepreneur support organizations (ESOs) for high-growth startups. With over 75 entrepreneur support organizations and another 22 co-working spaces aimed at the innovation community, Ellison said the area is fortunate that a number of those ESOs are concentrated in Cortex.

Since Cortex’s founding in 2002, 14 buildings have been built or redeveloped, with another five in some stage from late planning to near completion. Additionally, major events like the Startup Connection and STL Startup Week add to the robust and unique flavor of St. Louis’ innovative sector.

“Startup Connection is the biggest celebration of the St. Louis startup community, held each fall,” according to Ellison. “For one evening, we bring together the entire community to celebrate another great year of growth, to highlight 60 high-growth startups that are entering the market and to bring together the largest startup Resource Fair in the region.”

Looking Ahead

St. Louis has reasons to be excited about the future.

“St. Louis has a much larger and more vibrant startup community than people outside the region realize,” Cortex Innovation’s Ellison said. “We’ve been growing this for 25 years, and with the leadership of organizations like BioSTL, Cortex, Arch Grants, ITEN and others, the region has gone from a handful of entrepreneur support organizations in the late ‘90s to over 100 ESOs, co-working spaces and regional events today.”

While the original efforts were aimed at high-growth high-tech startups, today the community will find a broader mix of programs and spaces supporting artists and creatives, retail and product-focused startups, and woman- and minority-owned businesses, according to Ellison.

“A big part of that growth happened because the ESOs worked together to launch efforts that no one of them could have supported individually,” she said. “Events like Startup Connection (11 years old), the VISION conference, STL Startup Week and more, have been the result of several organizations working together to bring education and services to the St. Louis community.”

But not everything is perfect in Missouri’s largest city.

It’s important to be realistic about issues and areas for improvement to move forward in a meaningful way. Menietti from the Chamber has a few thoughts on the matter.

“We still have a lot of work to do around de-risking early-stage ideas and setting up pre-accelerator capital and programs,” he said. “I think we could be more intentional about community-building in the ecosystem and ensuring that funding and programs are accessible for traditionally overlooked and underrepresented founders. Nevertheless, I’m confident and excited about our ability as an ecosystem to come together and tackle these challenges in a collaborative, equitable way. The future is bright.”