Microplastics Mystery: A Journey from Macro to Micro

Microplastics represent a significant concern due to their widespread presence in oceans, posing both physical and toxicological risks to organisms.

These minute particles can be ingested by a diverse range of animals, spanning from small invertebrates to large mammals.

As a result, microplastics not only threaten marine life directly but also have the potential to enter the food chain, ultimately impacting human health.

Addressing the issue of microplastic pollution is crucial for safeguarding ecosystems and mitigating the broader environmental and health consequences associated with their presence in aquatic environments.

Microplastic Menace: From Origins to Environmental Crisis

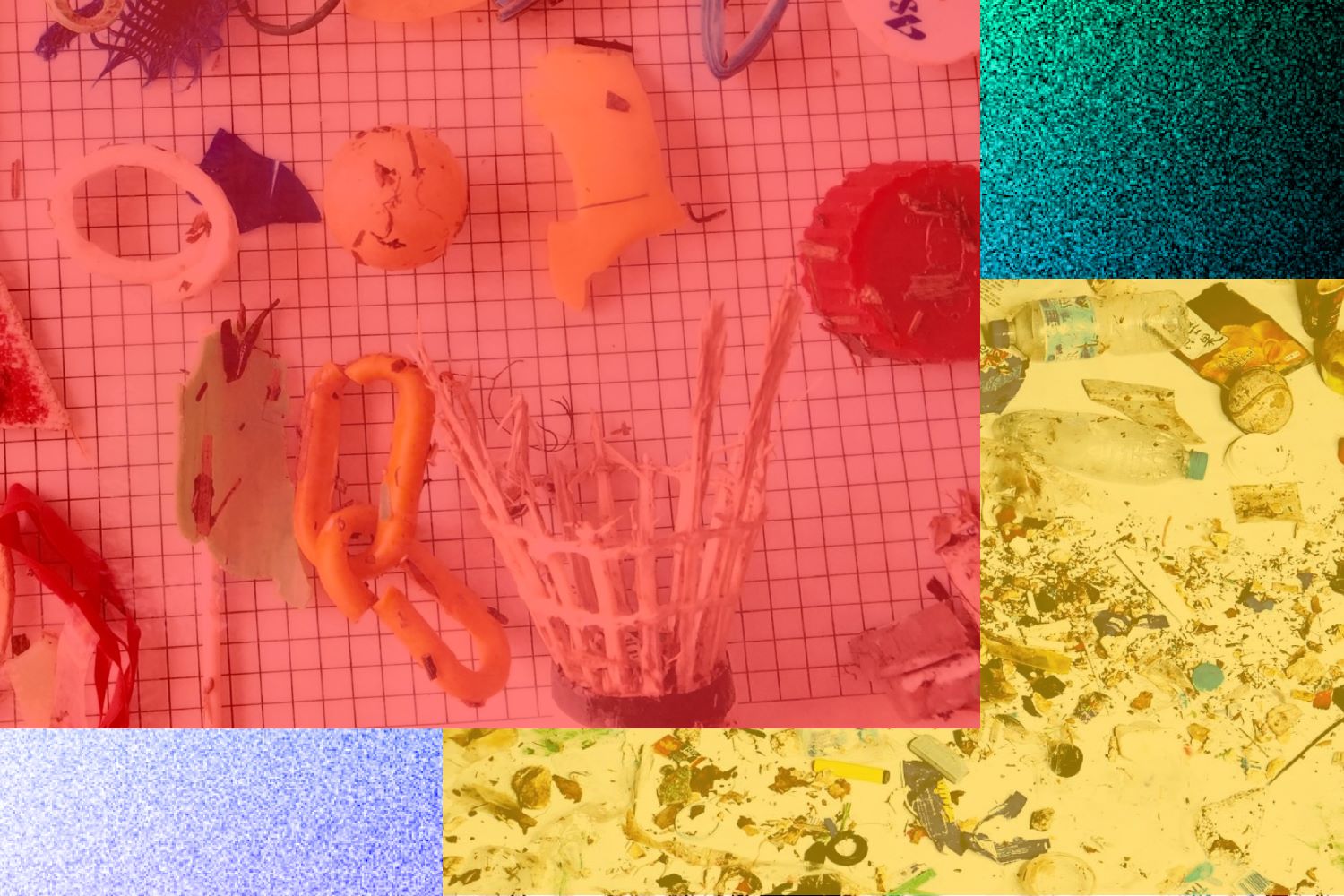

Microplastics, defined as plastic particles smaller than 5 mm in diameter. They come in two main types: primary and secondary.

Primary microplastics are intentionally manufactured for specific purposes such as exfoliating scrub beads or microfibers in clothing. Secondary microplastics are formed when larger plastic items degrade over time due to exposure to environmental factors like sunlight and mechanical abrasion from ocean waves.

The durability of plastic is both a boon and a curse. While its resilience makes it useful for a wide range of applications, it also means that plastic fragments can persist in the environment virtually indefinitely. Despite efforts to recycle and reduce plastic usage, the accumulation of microplastics continues to pose a threat to ecosystems worldwide.

The origins of the plastic industry can be traced back to the 19th century, where the quest for durable materials for snooker balls and billiard tables led to the creation of synthetic polymers as alternatives to natural materials like ivory.

The invention of Bakelite in 1907 marked a milestone, followed by other synthetic plastics like neoprene. World War II further fueled plastic production, leading to its ubiquitous presence in consumer products ranging from airplanes to Tupperware. In fact, plastic production exploded by 300% during this time, driven by wartime demands.

Post-war, the plastic industry faced a surplus of manufacturing capacity, leading to the proliferation of consumer goods like Tupperware, cellophane, and polyester clothing. However, this boom in plastic production also led to a corresponding increase in waste and pollution, both on land and in the oceans.

Despite advancements in recycling and heightened public awareness, the issue of microplastics persists. Matt Simon, in his book “Poison Like No Other: How Microplastics Corrupted Our Planet,” aptly describes microplastics as “pernicious glitter,” highlighting their pervasive and harmful nature.

Efforts to address the microplastic crisis require comprehensive strategies beyond mere recycling, emphasizing reduction in plastic usage, innovation in materials, and responsible waste management practices.

Microplastics: From Oceans to Our Bodies

Microplastics, microscopic plastic particles, have insidiously infiltrated every corner of the globe, from the remote reaches of Antarctic sea ice to the deepest ocean trenches. These tiny fragments pose a significant threat to aquatic life and ecosystems worldwide.

In 2022, microplastics were discovered in newly fallen snow in Antarctica for the first time. The concentration of microplastic particles in the melted snow was estimated to be 29 particles per liter, surpassing previous findings in Antarctic sea ice, which averaged around 12 plastic pieces per liter of water.

One of the alarming characteristics of microplastics is their ability to evade traditional water filtration systems. Despite their small size, they can pass through these filters, remaining undetected as they enter water bodies.

Once in the aquatic environment, microplastics pose a grave danger to marine organisms. Acting as carriers, they absorb and transport other harmful chemicals, creating a toxic combination detrimental to marine life.

Microplastics operate akin to a Trojan horse, infiltrating an organism’s digestive system and wreaking havoc on their health. Studies, such as those conducted on nematodes, have revealed the detrimental effects of microplastic exposure.

These organisms experience shortened lifespans, stunted growth, and reduced reproductive success, underscoring the profound impact of microplastics on the marine food chain.

The journey of microplastics begins at the bottom of the food chain, where plankton inadvertently ingest these particles. As larger organisms consume plankton and smaller fish, the cycle of contamination escalates, eventually reaching the food consumed by humans.

Despite the widespread infiltration of microplastics into the food chain, there is no need for immediate panic among seafood lovers or vegans. Surprisingly, the main exposure route for microplastics into our bodies is not through consuming contaminated seafood but through indoor inhalation and drinking from plastic bottles.

Researchers at the University of Plymouth conducted a comparative study, revealing that individuals are more likely to ingest microplastics through airborne microfibers shed by everyday items such as clothes, carpets, and furniture than through consuming contaminated seafood.

The discovery of microplastics in unexpected and previously unreported locations, such as deep within patients’ lungs and circulating in bloodstreams, has raised concerns about the potential health implications of these pervasive particles.

Microplastics and nanoplastics, with their diminutive size, have the capability to breach biological barriers, penetrating the skin, gut, and even the placenta. As a result, it’s increasingly evident that we are all now partially composed of plastic.

Reports from organizations like the WWF suggest that individuals may ingest up to a credit card’s worth of plastic each week, highlighting the extent of human exposure to these contaminants.

However, conflicting studies, such as those published by the ACS, propose lower estimates, indicating a weekly intake of only a few micrograms. While this discrepancy offers a glimmer of relief, it underscores the need for further research to accurately assess human exposure levels.

Scientists are particularly concerned about the potential health risks associated with microplastics. Could they trigger inflammation or cancer? Do they simply pass through the body, or do they act as endocrine disruptors, interfering with hormone function?

The Hidden Threat to Health and Ecosystems

Microplastics, minuscule synthetic particles pervading our environment, represent an enigmatic frontier in scientific inquiry, with their implications for human health remaining shrouded in uncertainty.

While animal studies have yielded disconcerting findings, mirroring concerns regarding tissue accumulation and reproductive health risks, their translatability to human physiology is fraught with complexities. The inherent differences in biology and metabolism between species underscore the need for cautious extrapolation when inferring potential health impacts in humans.

Furthermore, the intricate composition of microplastics, often imbued with a cocktail of chemicals and contaminants acquired from their environmental milieu, adds layers of intricacy to the puzzle. These particles, coated with bacterial biofilms and environmental residues, possess the capacity to interact with biological systems in unpredictable and potentially hazardous ways.

While larger microplastics have garnered attention for their tangible environmental impact, the respiratory risks posed by inhalation of smaller particles remain underexplored, representing a critical gap in our understanding.

The ubiquity of microplastics in everyday products, compounded by the leaching of chemicals like Bisphenol A (BPA) from plastic goods, introduces another dimension of concern. BPA, a ubiquitous industrial chemical, has been implicated in a litany of health issues, including endocrine disruption, cardiovascular disease, and reproductive abnormalities.

In recent years, studies have revealed the presence of microplastics in various parts of the human body, including the lungs, placental tissues, breast milk, and blood. Heather Leslie, a microplastics researcher formerly associated with Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and her team discovered microplastics in the blood samples of 17 out of 22 healthy adult volunteers in the Netherlands. This finding, published in Environment International last year, confirms suspicions among many scientists that these minuscule plastic particles can indeed be absorbed into the human bloodstream.

“We went from expecting plastic particles to be absorbable and present in the human bloodstream to knowing that they are,” Leslie says.

The findings come as little surprise given the pervasive presence of plastics in our surroundings. With their durability, versatility, and cost-effectiveness, plastics have become ubiquitous in our daily lives, found in everything from clothing and cosmetics to electronics and packaging.

Moreover, the variety of plastic materials available has grown significantly over the years. Heather Leslie notes that when she began her research on microplastics over a decade ago, there were roughly 3,000 types of plastic materials, whereas today there are over 9,600, each with its own distinct chemical composition and potential for toxicity.

Despite their durability, plastics undergo degradation over time. This degradation can occur through various means such as exposure to water, wind, sunlight, or heat, particularly in environments like oceans or landfills. Additionally, friction, as seen in the wear and tear of car tires, can lead to the release of plastic particles onto roadways during driving and braking.

In addition to investigating microplastic particles, researchers are also focusing on nanoplastics, which are particles smaller than 1 micrometer in length.

Dick Vethaak, a toxicologist at the Institute for Risk Assessment Sciences at Utrecht University in the Netherlands, who collaborated with Leslie on the study revealing microplastics in human blood, emphasizes that larger plastic objects in the environment break down into micro- and nanoplastics continuously, thereby increasing the overall number of particles.

Immunologist Nienke Vrisekoop of the University Medical Center Utrecht says, “If the microplastics are not clean … the immune cells [engulf] the particle and die faster because of if more immune cells, then rush in.”

Moreover, the pervasive nature of microplastics extends beyond their impact on human health, encompassing broader ecological ramifications. Synthetic textiles, constituting over 60% of the global textile market, shed microfibers during laundering, infiltrating water bodies and ecosystems with alarming efficiency.

While holding companies accountable for microplastic pollution is crucial, addressing the root causes demands a multifaceted approach. Localized efforts in regions like the Philippines and India, where microplastic pollution is particularly rampant, can make a substantial difference.

Plastic Predicament: A Call to Action for Innovation and Regulation

To catalyze meaningful change in regulations and innovation, experts must grapple with pivotal questions concerning alternatives, costs, and drawbacks.

The Potential of Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) in Biodegradable Plastics

Amidst the complexities, biodegradable plastics offer a glimmer of hope, with Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) emerging as a standout contender.

PHA shows potential as biodegradable plastics that numerous microbes can produce using diverse substrates sourced from waste materials.

Despite its efficacy in breaking down within months, the higher cost of PHA presents a barrier to widespread adoption. However, continued innovation holds promise for cost reduction, paving the way for a transition away from conventional plastics.

Regulatory Action: Addressing the Urgency of the Plastic Crisis

Global initiatives, from the U.S. ban on microbeads to France’s mandate for microfiber filters in washing machines, signal a collective commitment to mitigate plastic pollution.

Regulatory measures may mandate product labeling to educate consumers about the hazards of improper plastic disposal, available solutions, and the concept of extended producer responsibility, wherein producers must disclose their plastic usage data.

In March 2022, the United Nations Environment Assembly unanimously passed Resolution 5/14, titled “End plastic pollution: towards an international legally binding instrument,” marking a significant stride toward a plastic-free ocean.

Negotiations for the framework will unfold through a series of global meetings, aiming for completion by late 2024. The resolution’s preamble recognizes microplastics as part of plastic pollution, thus prompting the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to address both macroplastic and microplastic contamination in the upcoming global agreement.

Yet, challenges persist, and the efficacy of recycling initiatives remains uncertain, prompting a reevaluation of strategies to curb plastic consumption and promote sustainable practices.

Everyday Strategies: How People Address Microplastics in Their Daily Lives

Consumers, too, wield significant influence in the quest for solutions. Empowering individuals to make informed choices, advocating for policy reforms, and embracing a circular economy ethos are cited as effective measures endorsed by experts.

From adopting reusable containers to supporting product redesigns, every effort contributes to the collective endeavor to mitigate the plastic crisis.

However, the urgency of the matter cannot be overstated. With global plastic production soaring to unprecedented levels, surpassing biological materials on Earth, the stakes are alarmingly high.

Dr. Albert Rizzo’s poignant comparison to the smoking epidemic underscores the potential magnitude of the microplastics issue, urging proactive measures to safeguard public health.

“I can see Plastics being the same thing. Will we find out in 40 years that micro plastics in the lungs led to premature aging of the lung or empyema? We don’t know that. In the meantime, can we make Plastics safer?” Dr. Albert Rizzo said.

The urgency of addressing the plastic crisis is underscored by staggering statistics: in 2020 alone, a staggering 367 million metric tons of plastics were produced, with projections indicating a tripling of this figure by 2050.

“It is alarming because we are far into this problem and we still don’t understand the consequences, and it is going to be very difficult to back out of it if we have to,” Janice Brahney, a biochemist at Utah State University, said.

This exponential growth has propelled humanity into uncharted territory, where man-made materials now surpass biological ones on Earth. The relentless acceleration of plastic production has set humanity on a perilous trajectory akin to a treadmill racing toward an uncertain future.

Yet, disengaging from this plastic treadmill is far from simple. It requires a paradigm shift in societal norms, industrial practices, and consumer behaviors. The path forward demands unwavering commitment, innovative solutions, and decisive action from all stakeholders. Failure to confront this existential threat risks dire consequences for both the environment and public health.

Startups Tackling Microplastics Pollution in the US

Several startups are actively engaged in tackling this urgent concern, utilizing a range of strategies and technologies to address the pervasive presence of microplastics in the environment.

One such strategy involves materials engineering to develop filtration devices capable of removing microplastic fibers from the fashion supply chain.

For instance, companies like Baleena have pioneered filter technology that integrates into washing machines, capturing microplastic fibers released during the washing of synthetic clothing.

Additionally, other startups are focusing on the direct removal of plastics and synthetic debris from water sources and coastal areas.

They provide advanced data on plastic extraction while actively removing plastics and synthetic debris from water bodies and coastal regions.

These efforts not only help in reducing the accumulation of microplastics in the environment but also contribute to the preservation of marine ecosystems and the protection of wildlife.