Hard Truths about the U.S. Healthcare Sphere: Higher Spending, Poorer Outcome?

According to the stats following from the private U.S. healthcare foundation Commonwealth Fund that regularly ranks the health systems of a handful of developed countries, the best countries for health care are the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Australia. And the lowest performer? The United States! Whereas the U.S. healthcare is reported to spend the most, “this [ranking] is consistent across 20 years,” stated the Commonwealth Fund’s president, David Blumenthal, at the Spotlight Health Festival.

So, what’s wrong with the state of the healthcare industry? Why has the U.S. healthcare been falling short? Let’s read on to discover!

The Unpleasant Picture of The U.S. Healthcare System

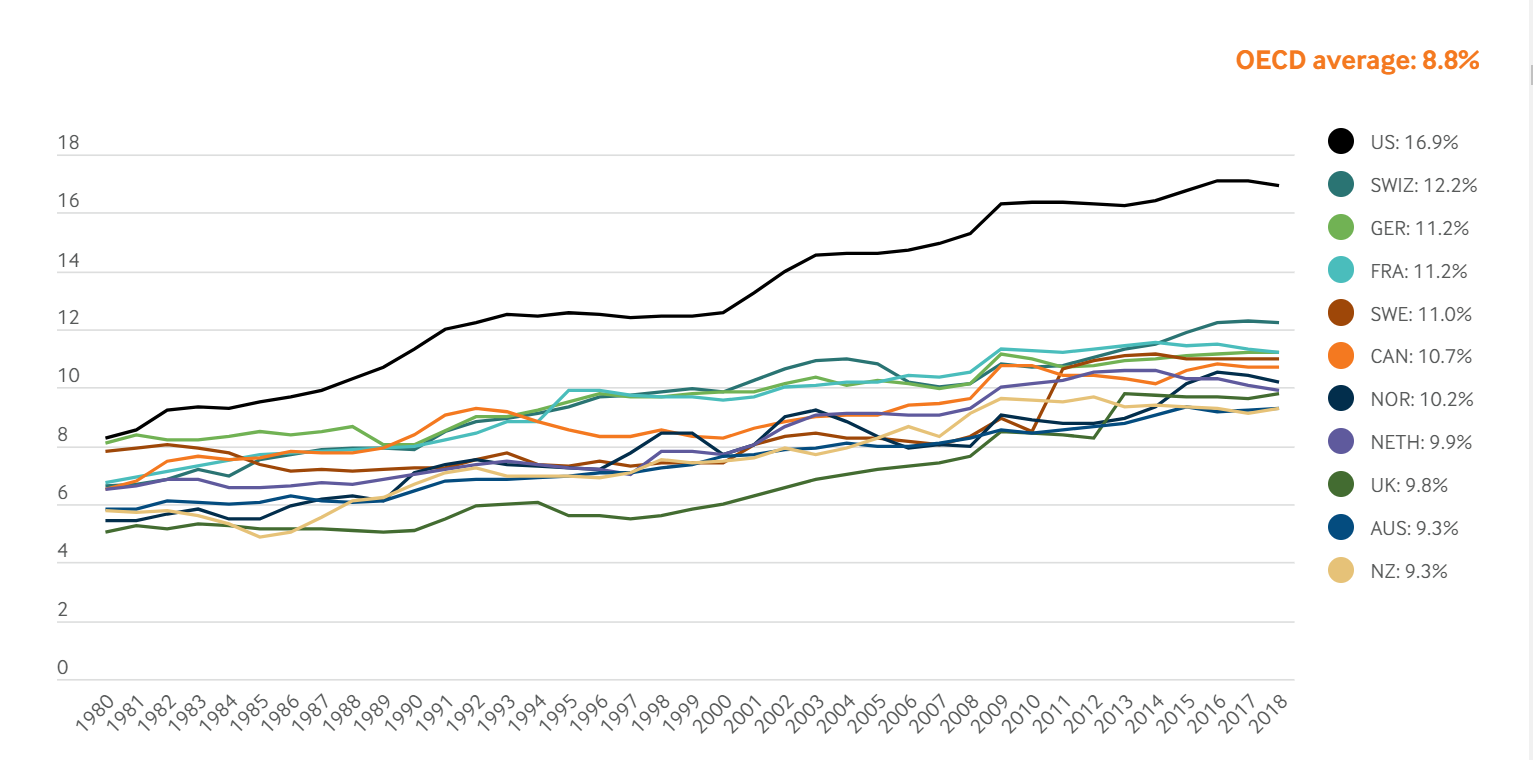

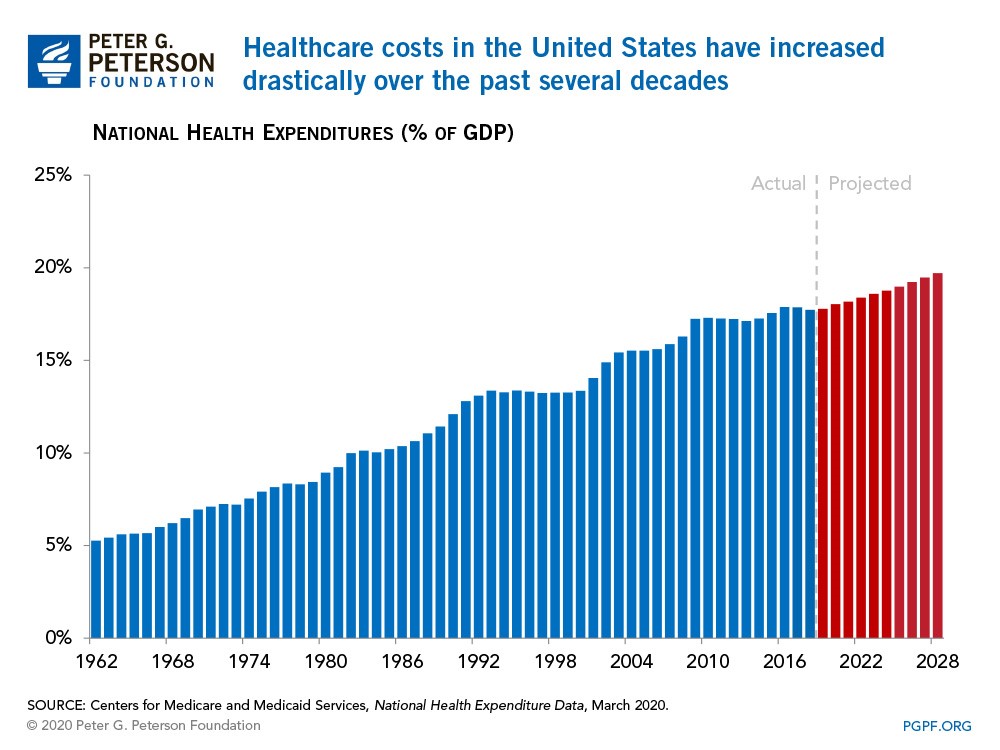

In 2018, the U.S. spent staggeringly nearly 17 percent of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) on health care sphere, nearly twice as much as the average OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) country. At the other end of the spectrum, New Zealand and Australia devoted only 9.3 percent, approximately half as much as the U.S. does. Additionally, the share of the economy spent on health care has been continuously increasing since the 1980s since health spending growth has outpaced economic growth, partly due to the advances in medical technologies, rising prices in the health sector, and increased demand for services.

Naturally, such a huge investment in the industry should have led to a better healthcare performance; nevertheless, this is absolutely not the case for the U.S. population.

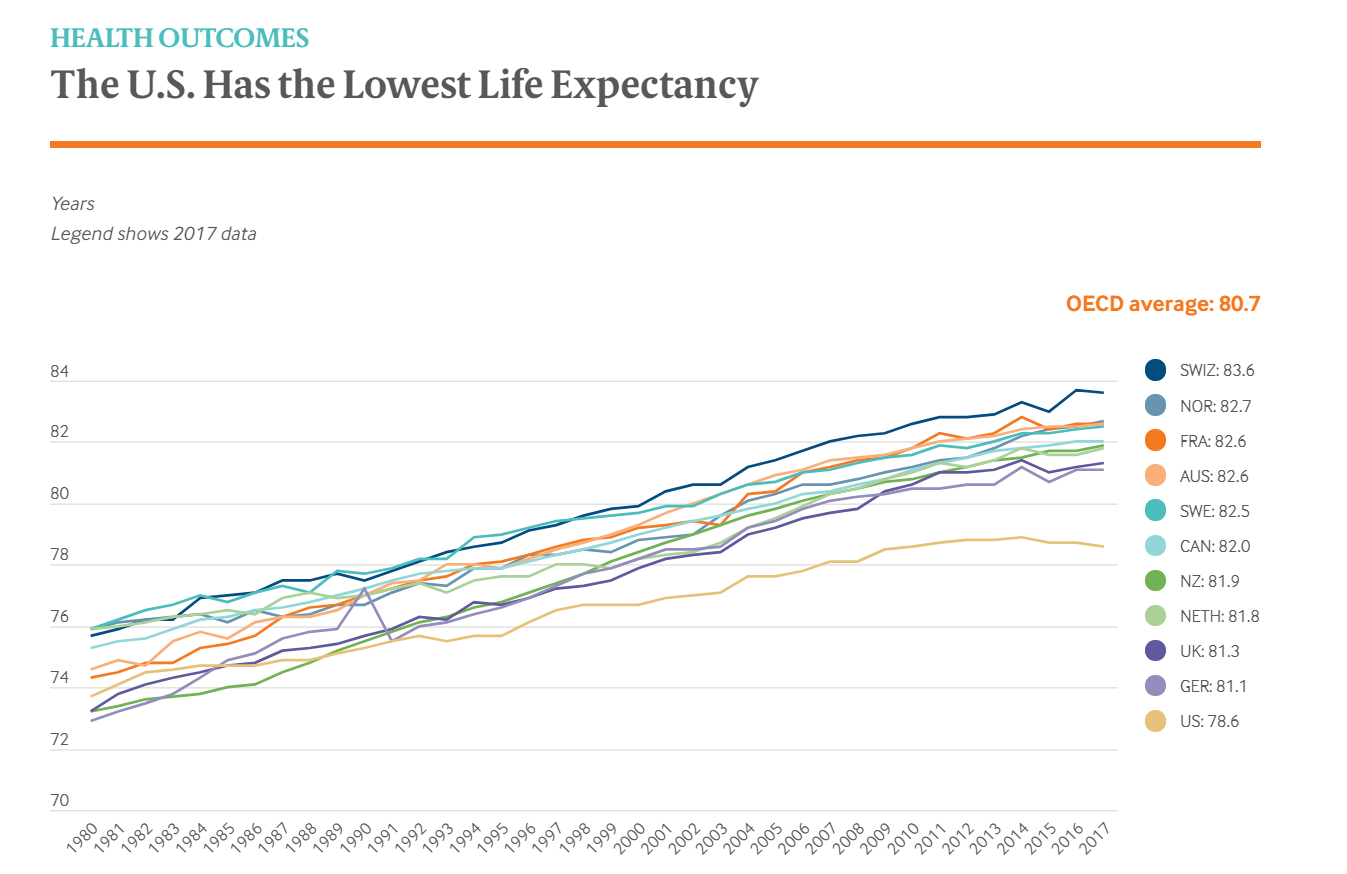

Notwithstanding the highest expenditure, Americans experience poorer health outcomes compared to their international peers. To be more precise, the life expectancy at birth in the U.S. was 78.6 years in 2017 — more than two years lower than the OECD average and five years lower than Switzerland, which has the longest lifespan. Furthermore, in the U.S., life expectancy masks racial and ethnic disparities. The average life expectancy among non-Hispanic black Americans is 75.3 years – 3.5 years lower than that of non-Hispanic whites, which stands at 78.8 years. Life expectancy for Hispanic Americans (81.8 years) is higher than for whites and similar to that in the Netherlands, New Zealand, and Canada.

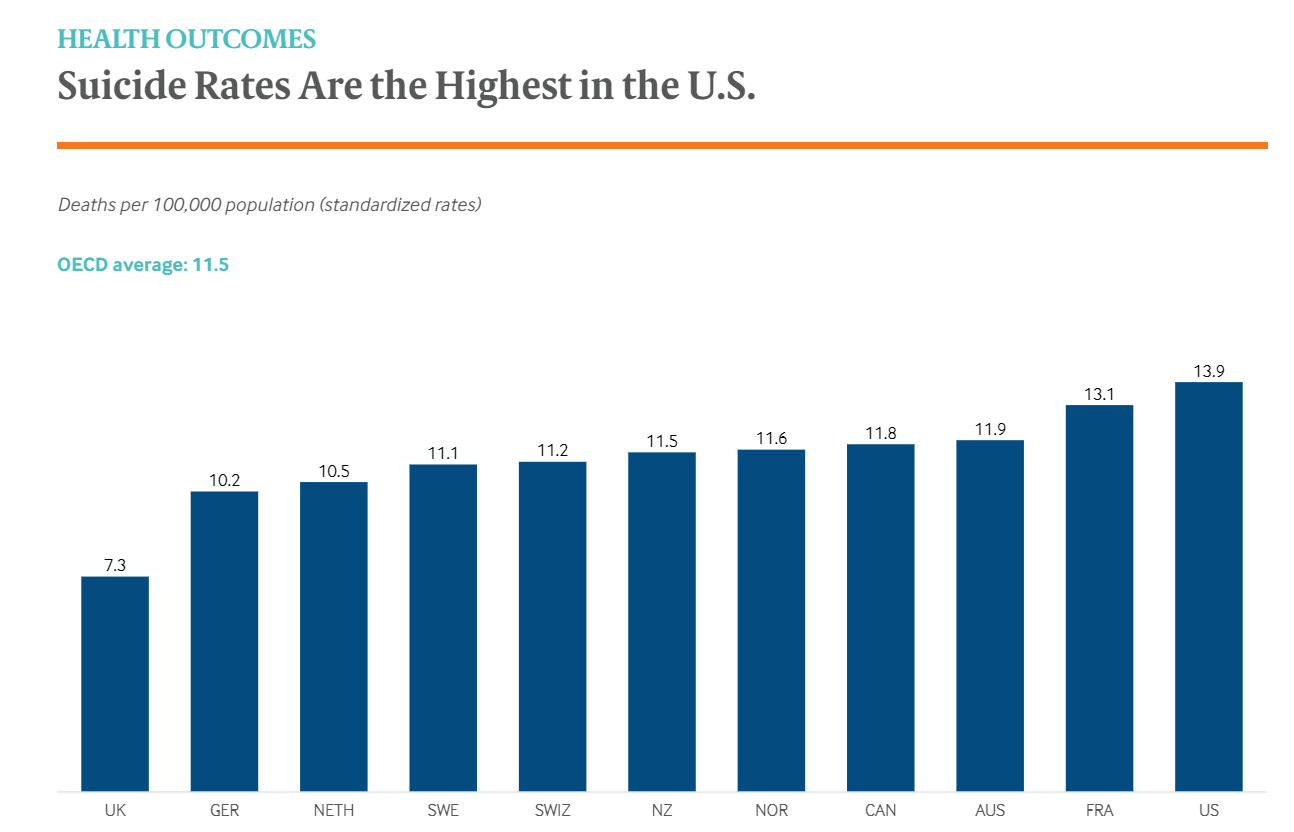

Reflecting shorter life expectancy, the United States of America has witnessed the highest suicide rate of these countries, with France a close second. In the meantime, the United Kingdom has the lowest rate – roughly half that of the U.S. The alarmingly elevated suicide rates may indicate a high burden of mental illness as well as numerous socio-economic issues which are yet to be addressed. The U.S. has seen an uptick in “deaths of despair” in recent years, which include suicides and deaths related to substance use, including overdoses.

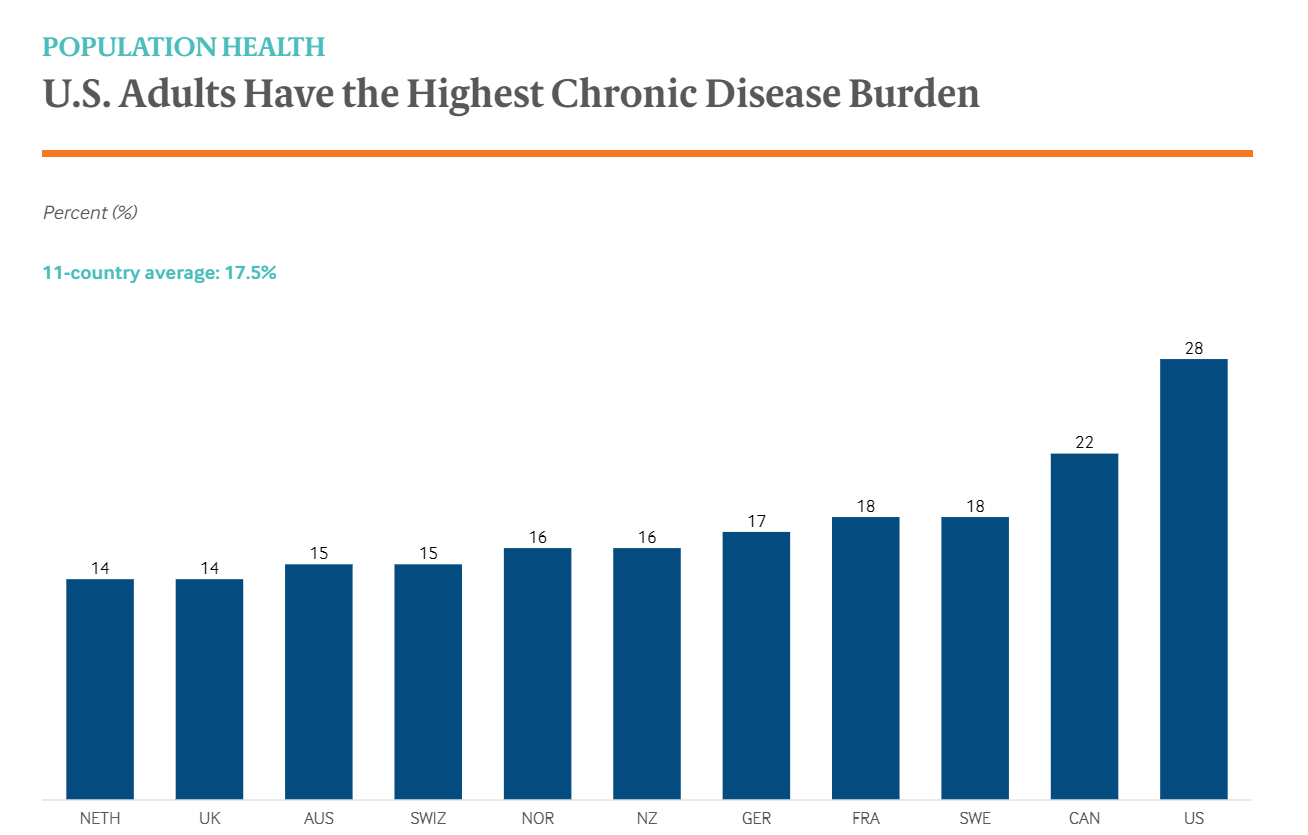

More seriously, the U.S. population is reported to suffer the highest chronic disease strains. In fact, whoppingly over one-quarter of U.S. adults claim they have ever been diagnosed with two or more chronic conditions such as asthma, diabetes, heart disease, or hypertension during their lifetime compared to 22 percent or less in all other countries. This rate is twice as high as in the Netherlands and the U.K.

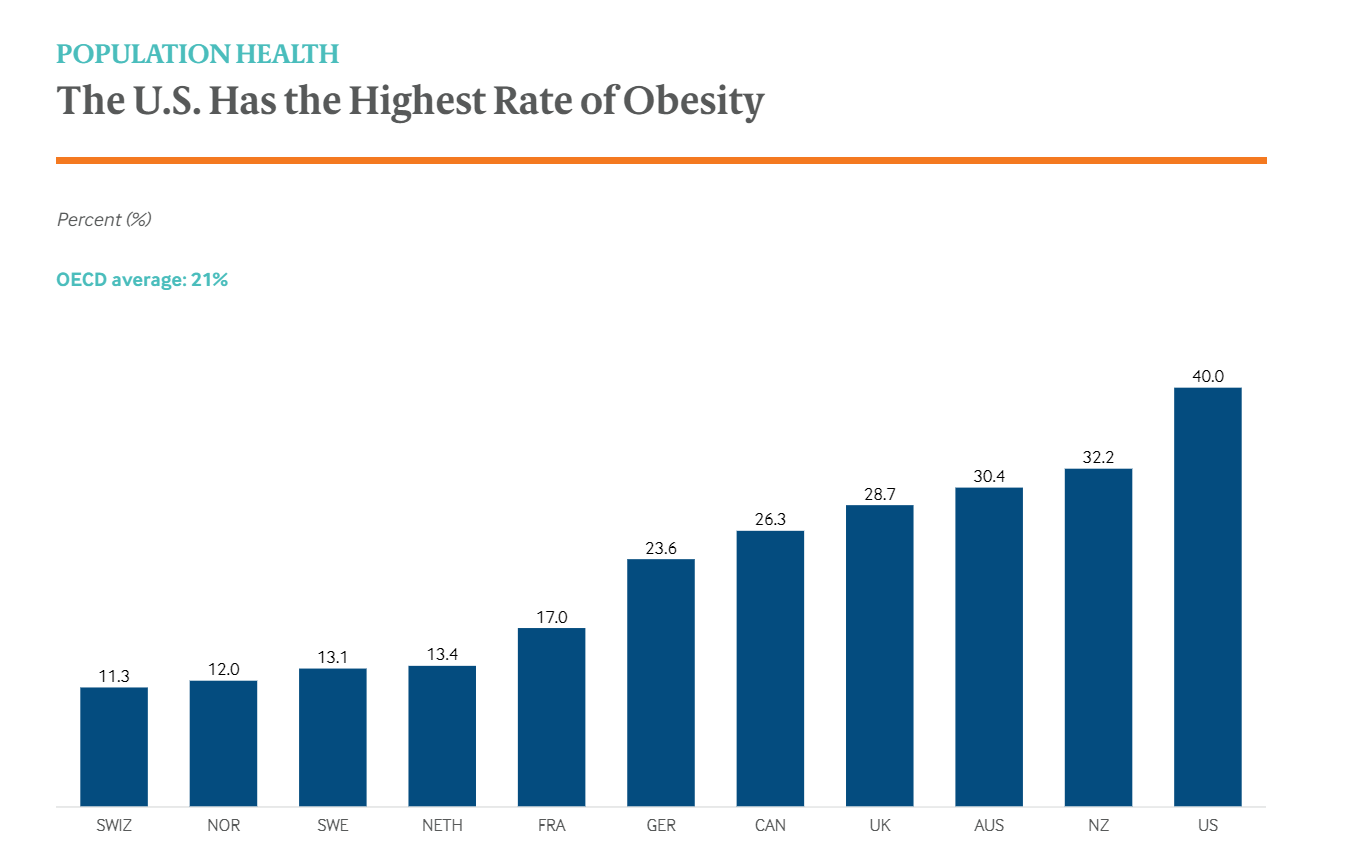

Whilst there is a plethora of reasons behind these chronic conditions, obesity is a key risk factor – especially when it comes to diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and cancer. And again, unfortunately, the U.S. observes the highest obesity rate among the countries studied, approximately two times higher than the OECD average as well as four times higher than in Switzerland and Norway.

It should also be noted that despite having the highest level of health care spending, Americans had fewer physician visits than their peers in most countries – on average, four visits per capita per year. The less-frequent physician visits may be attributable to the low supply of physicians in the U.S, which is roughly 2.6 practicing physicians per 1,000 population in 2018.

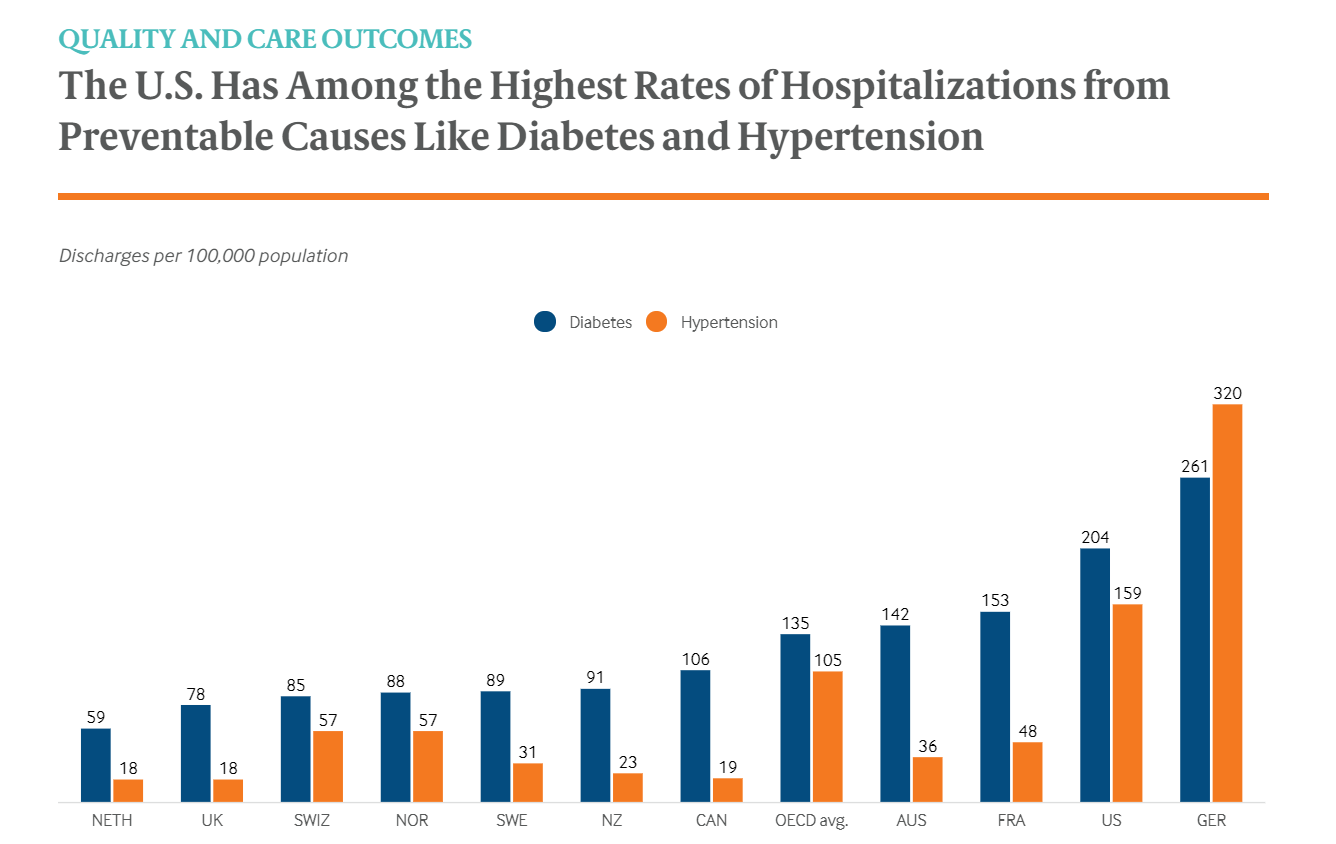

Notably, the U.S. healthcare industry also witnessed the high rate of hospitalizations for diabetes and hypertension – those diseases seen as ambulatory care–sensitive conditions, which means they are considered preventable with access to better primary care. In particular, such a rate was approximately 50 percent higher in the U.S. than the OECD average: the specific rate for hypertension-related hospitalizations was more than eightfold higher than the best-performing countries (the Netherlands, the U.K., and Canada), when, for diabetes hospitalizations, the rate was more than threefold higher than the Netherlands, the best-performing country.

One indicator adopted by several countries as a measurement of health system performance is “mortality amenable to health care.” This refers to premature deaths resulted from conditions that are considered avoidable with timely access to effective and high-quality health care (such as the already-mentioned two). And saddeningly, amongst 11 OCED countries, the U.S. has the highest rates of amenable mortality with staggeringly 112 deaths for every 100,000. Whereas the amenable mortality rate has dropped considerably since 2000 for some given countries, there has been less proportionate declined observed in the U.S. Such poor performance speaks out the sad truth that the U.S. population is granted worse access to primary care, prevention, and chronic disease management compared to their peer of other nations.

Key Reasons Behind the U.S. Health-Care System’s Poor Performance

So, why has the U.S. healthcare been falling short? Why does higher spending translate into worse outcomes? From the perspective of David Blumenthal, the Commonwealth Fund’s president, there exist three major reasons why the United States lags behind its peers so consistently.

Reason #1: Insufficient insurance coverage

First of all, it should be clarified that health care and health insurance are not equivalent, which means getting more people insured will not necessarily result in enhanced health outcomes. Nonetheless, “the literature on insurance demonstrates that having insurance lowers mortality. It is equivalent to a public health intervention,” stated Dr. David Blumenthal.

Looking at the real picture of the U.S. healthcare system, in 2018, an estimated 30.4 million people were uninsured, up from a low of 28.6 million in 2016. Coverage gains have stalled in most states and have even eroded in some. When it comes to examining why so many people remain uninsured, it is discovered that the majority of them can’t afford coverage, live in a state that didn’t expand Medicaid, or are undocumented. Those aren’t problems that people in places like the United Kingdom have to worry about.

Reason #2: Administrative inefficiency

“We waste a lot of money on administration,” stated Dr. Blumenthal. As the Commonwealth Fund’s most recent report reveals, in the United States, “doctors and patients [report] wasting time on billing and insurance claims. Other countries that rely on private health insurers, like the Netherlands, minimize some of these problems by standardizing basic benefit packages, which can both reduce the administrative burden for providers and ensure that patients face predictable copayments.”

Or to put it simply, whereas insurance coverage – by and large – is of great benefits, it’s not ideal that different insurance plans cover different treatments and procedures, forcing doctors to spend precious hours coordinating with insurance companies to provide care.

Reason #3: Underperforming primary care

“We have a very disorganized, fragmented, inefficient, and under-resourced primary care system.”

In practice, there remains a myriad of American primary-care physicians who struggle to receive relevant clinical information from specialists and hospitals, complicating efforts to provide seamless, coordinated care. On top of a lack of investment in primary care, “we don’t invest in social services, which are important determinants of health” Blumenthal added. To improve chronic disease outcomes, things like home visiting, better housing, and subsidized healthy food could extend the work of doctors and do a lot to help.

All things considered, it can be implied that expensive healthcare system – unaffordable insurance plan, costly health services, unnecessary administrative fees, etc. – emerges as one of the main root causes leading to Amerian’s worse health conditions. So, what is exactly the case in the U.S.? How expensive and how does such “expensiveness” disrupt the healthcare system transformation? Let’s see!

Hard Truths About The U.S Healthcare Sphere: Too Expensive Medical Bills

“They billed our insurance company over $3 million for the cost of the transplant. Then I have another EOB [Explanation of Benefits] right after it was it was another $1 million. So, you’re looking at a $4 million transplant. I don’t know what people do without insurance. How could you even begin to pay that?,” Ashley Palmiscino shared her insurance bill of roughly $4 million for her five-month-old son Luca’s lung transplant.

Her family had to turn to fundraising almost immediately just to keep up with the medical bills, and she’s not alone. One-third of the money raised on GoFundMe last year went to medical campaigns. The question is when the U.S. health care system did go from a philanthropic program to a multi-billion-dollar industry. And where do the funds go once the bills are paid?

Actually, the U.S. health care system is now in a sort of tug of war between physicians, hospitals, pharmaceutical companies, shareholders, and insurance companies – and caught in the center of it all are the patients.

“We’re often not able to provide the type of care that we want because of the cost of care.” “Those costs are now forcing a growing number of uninsured or underinsured Americans into traveling abroad for medical treatment.”

“Everyone started thinking of health care as a business where the metrics were profit, return on investment, efficiency, and those aren’t the metrics of health but that’s how we judge hospitals today,” shared Elisabeth Rosenthal, Former Physician, Author “An American Sickness.

When asked about medical aid, Ms. Ashley Palmiscino genuinely shared, “you would think that they would be looking out for your chronically ill children and all of the medications or things like parking at the hospital… No. No that’s not covered.”

There is a common belief that as hospitals are becoming more efficient, the cost to patients should go down too. Yet, in reality, that hasn’t necessarily been the case – there are several things that have to do with the billing system. Of course, doctors need to get paid and there are also admin costs and medical supplies and technology. But instead of, for instance, a three-page bill for patients in Belgium or some European countries, medical bills in the U.S. look more like this – a bundle of papers!

“I am my son’s secretary and I spent a lot of time taking care of just medical bills, and phone calls, and that type of thing.”

Discussing this concern, Dr. Elisabeth Rosenthal did genuinely share her points, “We talk a lot about the billers and the coders and the consultants who really are removed from health care. They’re not there because they care about health, they’re there because they see a business opportunity. And you know you can’t blame them in the sense that that’s what their companies are supposed to do. They’re looking for business, so a collection agency that does health care, you know to them a bill is a bill is a bill. They don’t care if it’s for somebody’s heart transplant or someone who was not very judicious and spent a lot more money on a Rolex watch that they couldn’t afford. It’s a bill.”

But, how come those bills are so long?

In reality, this kind of thing is typically termed “unbundling”. Let’s think of it like buying a plane ticket: You may come to pay for the ticket itself, but there exist a ton of extra charges squeezed into your final bill – let say, $30 for a checked bag, $50 for a few extra inches of legroom and another $3 for water.

Dr. Elisabeth Rosenthal went on, “people get irate about it in an airline ticket but in healthcare, we’ve kind of come to accept it as, “oh! that’s just normal.” And part of the reason I wrote the book [An American Sickness] is to say that’s not normal in other countries.”

To take a deeper look into the U.S. healthcare system, hospitals carry billing procedures through a complex system of codes: New patient visit: 99201-05; Emergency room visit: 99281-85; Burn due to water-skis on fire: V91.07. And of course, different codes mean different prices. For instance, when it comes to coding for a laceration, you’ll be charged a different amount depending on the size of the cut, where it’s at on your body, and how complex the suture is.

“Coding historically was about tracking diseases. But in the U.S., how you code a patient interaction is a billing construct. Again, something that would have scientific and medical purposes gets translated into a business asset.”

“Every day we spend hours going through checkboxes, typing notes, documenting things that we’re supposed to document for billing purposes, that we really don’t think improves patient care. The more that you spend time with computers, the more that we spend time billing, that means a lot less time for face to face interaction with our patients. And that’s why most of us got into medicine in the first place.” Shared Dr. Dhruv Khullar, Physician and Researcher at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Whereas, in principle, taking down all that data may be beneficial, it’s just not working in the U.S. As some doctors claim that they’re concerned about malpractice lawsuits, they order more tests to protect themselves; thus, bills keep getting longer, yet, health outcomes aren’t always getting better.

When facing the criticisms of the current hospital system, the American Hospital Association (AHA) declines to comment on, but they do have a fact sheet explaining that hospitals often don’t get paid the full amount that the bill. The AHA claims two-thirds of community hospitals lose money when the government pays Medicare and Medicaid bills. And that “the hospital payment system itself is broken!”

Plus, it’s understandable that a large proportion of that health care spending is on drugs and supplies, both of which can be hard to get insurance to fully cover. You may probably hear about the news when Martin Shkreli, then CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals and the notorious “pharma bro,” jacked up the cost of the lifesaving drug Daraprim by 5,000 percent with its price tag escalating from $13.50 a pill to $750 overnight. But what about Colchicine or Epinephrine? The prices of those drugs have both skyrocketed because one company has control over it. The response is usually the same, the companies need to raise prices to fund the research and development for the next drug.

As Dean Baker, Senior Economist, Center for Economic Policy & Research stated, “For the most part high priced drugs have patent protection from the government. They pretty much have a monopoly in a market, so very often you have someone who needs a specific cancer drug. One company makes it, they’re the only company that makes it, no one else can make it. And since it might be absolutely necessary for your life, they’re in a position where they could charge anything they want.”

It’s also critical to remember that many of these costs are adding up during a very stressful time. Sometimes the people paying the bills aren’t even conscious. “The analogy I often make is firefighters when they come to a burning house. So, when your house is on fire, your family’s inside, you don’t want to be sitting there negotiating with firefighters. Oh you know I’m going to pay you $300,000 they want $400,000. That’s not how you want to do this. And often health care does have that character.”

Furthermore, medical emergencies are chaotic and health insurance is also so confusing. There are HMOs, PPOs, deductibles, copays, and premiums to try and make sense of. You would think that if people are getting insured, they shouldn’t have to pay that much out of pocket – but that’s not always the case. In fact, not every doctor accepts every insurance plan. And even some hospitals have staff employed by multiple third-party companies. So, one trip to the Emergency Room, for example, may possibly get someone five different bills and his/her insurance might only cover one.

For the time being, the insurance companies are supposed to be negotiating their prices lower because – in several cases – they’re ultimately the ones footing the bill. “Health costs and contribute to all sorts of inequalities in society. So, people who are poor or middle class even, they’re just one serious illness away from bankruptcy.”

The Bottom Line

Whereas high healthcare spending is not necessarily a bad thing, especially if it leads to better health outcomes, that is not the case in the United States – the nation lagging behind other high-income countries. Expensive healthcare costs with bundles of medical bills put pressure on an already strained fiscal situation. To address the inefficiencies of the investment budget as well as tackle the concerns over the costly medical expense, urgent action from governmental agencies should be duly taken.