Lesson from the Fall of Groupon: A Tale of Shifting Fortunes

In the early 2010s, Groupon was a name synonymous with rapid growth, innovation, and the future of e-commerce.

As one of the pioneers of daily deals and group buying, Groupon offered consumers unprecedented discounts on a wide array of products and services, from gourmet dinners to spa treatments.

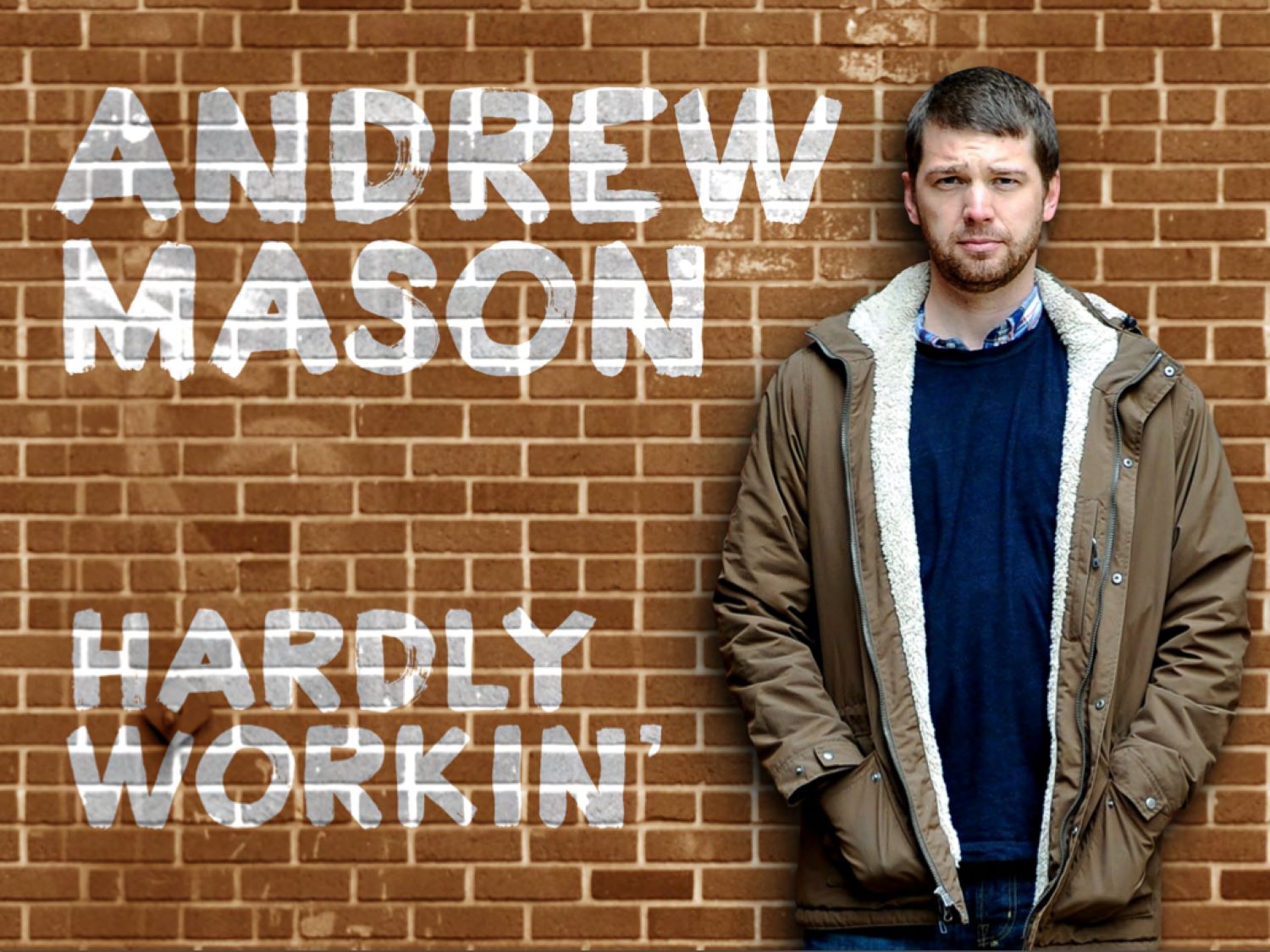

With its charismatic founder, Andrew Mason, at the helm, the company became one of the fastest-growing tech startups in history, valued at billions of dollars.

However, what followed was a precipitous decline that saw Groupon’s fortunes unravel, ultimately challenging the very core of its business model.

From Aspiring Musician to Tech Trailblazer: The Groupon Founder’s Unconventional Path to Success

Andrew Mason’s college years were characterized by a deep-seated passion for music, and he nurtured dreams of becoming a rock musician. However, fate had a different plan for him. After a stint in higher education studying music, he pivoted into the world of technology, having taught himself coding.

His first foray into the tech industry began with a job at Inner Workings, where the seeds of an idea were sown, an idea that would eventually germinate into Groupon.

It was Mason’s chance encounter with tech billionaire Eric Lefkofsky that catalyzed the creation of what would become Groupon. During one of their interactions, Mason discussed a concept for a website he wanted Lefkofsky to back financially.

This initial project, dubbed “thepoint.com,” had a noble premise: it allowed individuals to initiate and sign petitions in support of positive changes. Despite garnering attention, the venture proved unsustainable.

However, Mason did not abandon the core concept, but rather adapted it. He retained the technology and, crucially, the togetherness mentality, and thus, Groupon was born.

Groupon, conceptualized by Andrew Mason, burst onto the scene in 2008 with a deceptively simple yet groundbreaking concept: digital coupons. For centuries, retailers had relied on paper coupons to attract customers, and Groupon brought this tried-and-true concept into the digital age.

In its early days, Groupon operated with a small and dedicated team. They established partnerships with local merchants to offer daily deals and promotions, but with a unique twist. Each deal required a minimum number of customers to sign up for it to become active, creating a built-in incentive for users to share these enticing deals with their friends and family.

Groupon’s entry into the market was a breath of fresh air during troubled economic times. It provided a platform for both deal-seekers and local businesses looking to expand their reach. The media and investors hailed it as a harbinger of a new era in shopping.

Within a mere three years, Groupon had become the fastest-growing startup, operating in 35 countries and boasting a subscriber base of 150 million.

Andrew Mason’s brainchild was a simple yet effective one: attract merchants to offer coupons online through Groupon’s platform and email subscriber list. Shoppers, whether on their computers, tablets, or mobile phones, could purchase these coupons, securing discounts on an array of products and services tailored to their cities and preferences. The result was Groupon’s unique marketplace.

By 2010, Groupon had expanded its reach to nearly 100 cities across 25 countries, and its staff had grown to almost 10,000 employees.

For Mason, who had just turned 30, the journey from a graduate student building websites on the side to a tech billionaire in the making was well underway.

Andrew Mason and the Mismatch with Silicon Valley Culture

Delving deeper into Andrew Mason, his challenges within Silicon Valley’s intricate ecosystem reveal a nuanced interplay of cultural, strategic, and perceptual factors.

The belated decision to establish an office in Silicon Valley implies a missed opportunity to tap into unparalleled coding talent.

The analogy of Silicon Valley as playing for the Yankees underscores the harsh, competitive environment where success amplifies, but failure is magnified equally.

The prevalent cult of the founder, often celebrated for visionary ideas, grants young leaders’ considerable freedom despite their limited management experience, creating a dichotomy between autonomy and potential recklessness.

The significance of mentors in Silicon Valley is emphasized, emphasizing that successful founders recognize the value of surrounding themselves with experienced advisors.

Groupon’s geographical separation, rooted in Chicago, potentially limited its exposure to the constant mentoring and scrutiny typical of the Valley’s ecosystem.

The characterization of Groupon as a “spoiled only child” illustrates the company’s unique position — a prominent player both in Chicago’s tech landscape and on a global scale.

Besides, Groupon’s initial backlash was notably triggered by its Super Bowl ads.

The intentionally cheeky advertisements, transitioning from saving the whales to sushi deals, caused offense, and Groupon had to swiftly backtrack, pulling the ads and issuing apologies.

This experience, though not severely damaging, marked a departure for Groupon, as the company had not previously encountered such negative public sentiment.

The narrative suggests that Groupon’s honeymoon period was short-lived, and the real challenge emerged with the impending S1 backlash during the quiet period before going public.

The frustration with the press and potential investors’ concerns about financial and business viability were conveyed through leaked emails, memos, and PR tantrums.

This approach, described as “cheeky,” seemingly aimed to control the narrative and shape public perception during a critical phase.

Google’s Pursuit: A Billion-Dollar Deal That Never Materialized

In 2010, the tech world was abuzz with the news that Google, one of the internet’s most prominent giants, was keen on acquiring Groupon, a burgeoning company that had taken the e-commerce and coupon industry by storm. The reported offer was a staggering $6 billion, but the deal ultimately remained elusive, marking a turning point in both companies’ histories.

Google’s interest in Groupon was not unfounded. Groupon had rapidly ascended the ranks of tech startups, gaining a reputation as one of the fastest-growing companies globally. The concept of offering daily deals and group buying had resonated with both consumers and businesses, and Groupon had a massive subscriber base of 150 million users in 35 countries.

The allure of Groupon’s vast user base and what it seemed to be an innovative business model, which incentivized customers to share deals with friends and family, was evident to Google. The search engine giant, with its significant resources and expansive reach, saw the acquisition as a strategic move to bolster its position in the e-commerce and local advertising sectors.

The negotiations were carried out behind closed doors, with the anticipation of a landmark deal that could potentially reshape the e-commerce landscape. Google’s bid was perceived as a testament to the increasing importance of the local advertising market, a sector in which Groupon had excelled with its community-focused approach.

However, as the talks progressed, Groupon faced a critical decision. While the $6 billion offer was a substantial sum, it was viewed by some as undervaluing the company’s true potential. Groupon’s leadership team was also confident in their ability to navigate the competitive e-commerce landscape independently.

In December 2010, Groupon made a surprising and bold move, rejecting Google’s multi-billion dollar acquisition offer. Instead, the company chose to pursue its own path by preparing for an initial public offering (IPO) in 2011, a move that would eventually be one of the biggest IPOs since Google’s own stock market debut in 2004.

However, what seems to unlock the gate to heaven turned down to be misery, the path forward for Groupon would prove to be fraught with challenges.

Navigating Turbulence: Groupon’s Diversification and Financial Struggles

Groupon’s inception in 2008 coincided with economic uncertainty, providing an ideal environment for its group-buying model. The aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis saw consumers actively seeking discounts, propelling Groupon’s early success. The company’s strategic timing aligned with a consumer base eager for deals amid economic hardship.

As Groupon thrived in the post-crisis economy, the group-buying model capitalized on widespread interest in collective savings. The platform’s promise of significant discounts resonated with a financially conscious audience, leading to substantial user growth.

During this period, businesses, grappling with uncertainties, welcomed Groupon’s ability to generate guaranteed demand, creating a mutually beneficial dynamic.

However, Groupon’s advantageous positioning shifted post-2010 as the economy regained strength. The recovering financial landscape reduced the urgency for consumers to seek collective deals, eroding the foundation of Groupon’s model. The company faced intensified competition in the online marketplace, with major players entering the daily deals space.

Moreover, Groupon’s decision to decline Google’s acquisition offer in 2010 that mentioned above reflected confidence in navigating a competitive landscape.

Nevertheless, as the economy strengthened, businesses gained more negotiating power, contributing to shrinking profit margins on new business lines.

Groupon’s inability to maintain strong bargaining power with suppliers and the evolving consumer behavior further challenged the sustainability of its group-buying model.

In June 2011, Groupon made a bold move onto the public stage, filing for an Initial Public Offering (IPO) valued at $750 million. The decision was a pivotal moment for the company, marking its transition from a rapidly growing startup to a publicly traded entity.

Groupon’s IPO filing provided potential investors with insight into the company’s history, philosophy, and future aspirations. CEO Andrew Mason’s letter to potential stockholders outlined the company’s journey, from its roots in The Point, a social action platform launched in 2007, to the evolution of Groupon as a dominant force in the group-buying market.

The IPO was met with both anticipation and skepticism. On one hand, Groupon’s explosive growth, with over 7,000 employees and operations in 43 countries, showcased its market dominance.

However, the decision to go public also exposed the company to heightened scrutiny, forcing it to address concerns about its profitability and long-term sustainability.

After that, the company’s stock price took a nosedive, with investors who had put $100 into the company on IPO day seeing the value plummet to just $20 within a year. In the present day, that once-promising investment has dwindled to near insignificance.

After Groupon’s stock had dropped to a quarter of its IPO price, Mason was fired, and his tenure is perhaps best recalled by the frank letter he sent to employees announcing his departure: “After four and a half intense and wonderful years as CEO of Groupon, I’ve decided that I’d like to spend more time with my family. Just kidding — I was fired today. If you’re wondering why … you haven’t been paying attention.”

In the years that followed, Groupon weathered storms, and attempts at diversification, including forays into the restaurant delivery sector, marked strategic shifts

Groupon’s foray into the delivery sector hinted at a fresh direction, aligning with CEO Eric Lefkofsky’s vision to capitalize on “online food ordering and delivery” as an untapped opportunity.

This strategic pivot was later fortified with the launch of Groupon To Go, a delivery service that initiated trials in Chicago.

Groupon’s foray into restaurant delivery presented an opportunity to explore a sector estimated to be worth $70 billion.

However, as the company ventured into delivery, the challenge lay in offering a compelling proposition that could outshine established platforms like Seamless and GrubHub.

The question remained whether Groupon To Go could effectively transform the company’s fortunes, breathing new life into a brand that had faced significant turbulence.

The restaurant delivery space was fiercely competitive, with customer convenience and satisfaction at its core. While Groupon’s initial value proposition revolved around deals, the delivery space required a new approach.

It was clear that success hinged on not just securing restaurant participation but also ensuring a smooth and reliable fulfillment process. As such, Groupon To Go was embarking on a journey fraught with challenges, including the need for an enticing customer-facing portal, seamless credit card processing, and the daunting task of competing with established delivery giants.

As of its initial launch, Groupon To Go faced the immediate hurdle of differentiating itself from the competition, a task complicated by the fact that the main incentive offered was a temporary 10 percent discount on all orders.

Recognizing the challenges that arose from this diversification, Groupon made the wise decision to return to its origins as a digital coupon provider.

The timing of this return to its core focus was fortuitous, allowing Groupon to sidestep the inventory-related issues that have troubled many retailers in recent times. However, despite the shift back to digital coupons, Groupon’s second-quarter results for 2022 suggest that the new direction hasn’t proven as successful as initially anticipated.

CEO Kedar Deshpande candidly acknowledged that the company’s overall business performance fell short of expectations and emphasized their proactive measures to enhance their trajectory.

However, this update, while transparent, raised legitimate concerns about the viability of this corporate shift. Despite Deshpande’s confidence in Groupon achieving positive cash flow by the end of 2022, current numbers do not wholly support his optimism.

A telling example comes from North America, where revenue declined by 30% year-over-year, attributed to a “decline in engagement on the platform.” While the shift away from physical goods played a role in this decline, Groupon’s coupon business, as reflected in the number of active local customers, only grew by a marginal 1% in North America. Given that North America constitutes nearly three-quarters of Groupon’s business, bolstering this division is crucial for long-term success.

The international performance was even more concerning from a sales perspective, despite an impressive 22% increase in the number of local customers. When considering Deshpande’s remarks and the financial results, including an adjusted quarterly loss per share of $0.34, it becomes evident that these numbers are insufficient to steer Groupon back on track.

Compounding these challenges is the fact that Groupon holds a little over $315 million in cash on its balance sheet, which rapidly depleted by $183 million during the first half of 2022. The reduction in cash burn during the second quarter, amounting to $87 million compared to the prior year’s $281 million, is encouraging.

However, time is of the essence, as the current burn rate leaves the company with less than a year’s worth of cash on hand. To secure its financial stability, Groupon must expedite its journey toward positive cash flow.

The attempt to diversify into selling physical goods did not yield the desired results, making this a critical juncture in Groupon’s history.