Tech Startup ‘Box’: Rich, But Not Quite Silicon Valley Rich

The myth of the college student who drops out to create the world’s next technological innovation in their garage is one of Silicon Valley’s most well-worn tropes. Yet every few years, a visionary young entrepreneur emerges who genuinely does change the world with their startup.

Aaron Levie, co-founder and CEO of Box is one such entrepreneur. Since founding Box in 2005 during his time as a student at the University of Southern California, Levie and his co-founders have grown the company to become one of the premier enterprise IT firms in tech.

They rang the New York Stock Exchange’s (NYSE) opening bell in 2015 to mark Box’s debut as a public company, a rite of success that few Silicon Valley startups live long enough to see. But getting there took a decade, and stress made the 35-year-old Levie’s wild hair grey at the temples.

Box in 2020: It Is Now a Profit Story

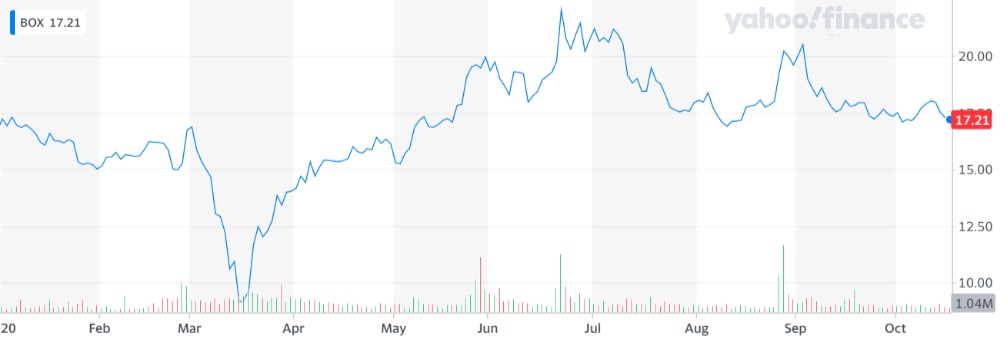

A few years back, investors would get laughed at if they thought Box would ever be a story about profitability rather than growth. Not long after Box went public in 2015 at $14 per share (barely below where shares trade now, in contrast to the wild gains seen by other software companies post-IPO), Mark Cuban famously called the company a “house of horrors” for the magnitude of its losses. But fast forward a few years later, Box has shown us concrete proof that young and money-losing software startups can eventually build on their strong gross margins and ratchet back sales expenses as they mature in order to eventually deliver profits and cash flow.

This profitability story was demonstrated clearly in Box’s recent earnings release. In spite of strong results and a bullish outlook, shares of Box barely budged:

The biggest fundamental shift in Box’s growth trajectory, of course, is the coronavirus – which for Box may end up actually being a long-term benefit, even if near-term sales are pressured. Many technology companies have come to rely more on remote work, with some like Twitter announcing that they would allow their employees to continue working remotely indefinitely. Such flexible work arrangements depend on strong cloud infrastructure and collaboration tools to work, which is exactly what Box provides.

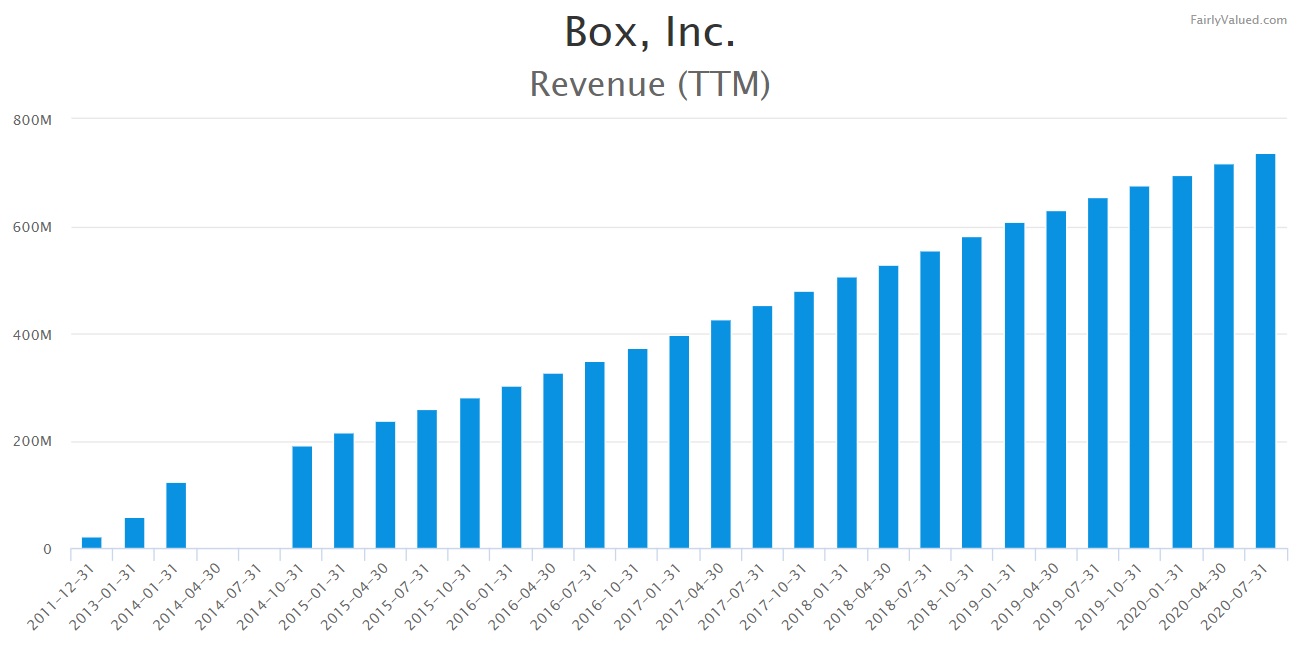

Box is actually one of the few companies to provide full-year guidance for the calendar year 2020, potentially a testament to the stability of its revenue stream and the company’s visibility into it. For the current year, Box is planning for $760-$768 million in revenue, representing 9-10% y/y growth (this may be a few points on the light side, as Box generated 13% y/y growth in Q1).

Box CEO Aaron Levie is not shy to share about how the pandemic has pushed companies to move to the cloud much more quickly than they probably would have. He said as a digital company, he was able to move his employees to work from home and remain efficient because of tools like Slack, Zoom, Okta and, yes, Box were in place to help them do that.

All of that helped keep the business going, and even thriving, through the extremely difficult times the pandemic has wrought. “We’re fortunate about how we’ve been able to execute in this environment. It helps that we’re 100% SaaS, and we’ve got a great digital engine to perform the business,” he said.

He added, “And at the same time, as we’ve talked about, we’ve been driving greater profitability. So the efficiency of the businesses has also improved dramatically, and the result was that overall we had a very strong quarter with better growth than expected and better profitability than expected. As a result, we were able to raise our targets on both revenue growth and profitability for the rest of the year.”

How Levie & Friends Built Their Billions Empire Without Stabbing Each Other’s Back

Every startup has a story. Too often, as demonstrated with Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat, those origin stories are crammed with ego and infighting over money and control. In contrast, the history of Box seems refreshingly straightforward. So, how did Aaron Levie and his childhood friends successfully build Box Inc. into a $2 billion business without stabbing each other in the back?

Growing Up Entrepreneurs

“I don’t even remember life before Box. I’ve been doing this as far as my memory goes back. I assume that I was born and just got into the cloud storage industry right after that moment. That’s about where my memory trails off,” Levie remarked.

Box as a platform and company was born in 2005, but even that was well after the establishment of the friendship between Levie and his co-founder and Box’s chief financial officer, Dylan Smith.

Smith and Levie met as classmates at Islander Middle School in Mercer Island, Washington, a suburb southeast of Seattle, and then went to Mercer Island High School together.

“Even back then he started getting me interested in entrepreneurship,” Smith recalled. “He was much more interested in technology than business back then.”

Two other key members of the Box team were also childhood friends.

Jeff Queisser, currently vice president of Box’s technical operations, met Levie when they were in the fourth and fifth grades, respectively, as neighbors. By high school, Queisser recalled that the two were starting “kind of crazy businesses.”

Sam Ghods, now vice president of technology at Box, joined the group in the 10th grade when his family relocated from Illinois to Mercer Island. The same year in school, Ghods recalled that he and Queisser became friends on the bus to school, eventually hanging out more frequently with Smith and Levie as well and getting involved in various business schemes.

In high school, Levie’s parents’ hot tub served as the discussion forum.

“We would get a call at about 12:30, and it would be Aaron, ‘What do you think about this? I think this could be absolutely insane. Like, come over right now. I got towels, just bring shorts, come over,'” Queisser remembers. “This would be at 12:30 and by like 12:40, we were in his hot tub just iterating ideas.”

“We all grew up together,” Levie reminded. “We’ve done lots of different businesses and projects, some technology, some other, throughout high school. Then we kind of went our separate ways, and decided to regroup for the cloud industry.”

From Research Paper to Funding

The idea for Box originated from a research project that Levie, who was then a college student at USC, was working on in 2004. Levie’s project examined storage options and in the process of researching his paper he discovered how fragmented the market was. He called up 10 random businesses and asked how they are storing content and data and received ten different answers.

Back then, Levie realized in his research that even though there were no iPhones, tablets or Android phones, people still wanted to access data from different places. These places just happened to be extinct technologies now, he adds, joking that the Palm Trio was back then a prime destination to find documents.

“The opportunity I saw was to build something that would change how you want to get your information,” he explains. At the time, many thought Gmail would be sufficient for storing data. But Levie felt there was a real business behind where to store data and this was in the cloud. The name Box came from his vision of storing data in a virtual box in the cloud.

During the Winter Break of 2004, Levie shared his idea with Smith. Both Smith and Levie had toyed around with startups in the past and had dreams of starting their own companies. The boys shared Levie’s passion for the cloud storage idea and by the Spring of 2005, Levie, Smith and his friends were actually developing a product. Box, at the time, was simply an online file storage service where users could pay to store files in the cloud.

This was all happening in between classes, says Smith, who was enrolled at Duke, and in order to fund the early days of Box in 2005, Smith invested $20,000 of money he earned playing online poker. The team actually launched the product in February of 2005 as a simple file storage product for both consumers and enterprises. Levie and Smith sent their pitches to the media and landed coverage on sites like Gizmodo, where they offered free storage incentives for new customers. The fledgling startup quickly accumulated a few customers and began its journey as a real service.

Once the decision was made to leave their respective colleges, Aaron (then 21) and Smith (then 20) mutually agreed that Silicon Valley was the best place to be. The pair packed their bags and moved to Berkeley, California in early 2006, where Levie’s uncle rented them a small garage. As Smith recalled, both Levie and him worked and lived night and day out of the garage, soon joined by high school friends from Mercer Island, Jeff Queisser and Sam Ghods.

Then came that fateful Spring day at Arrington’s house, where Levie and Smith pitched Melton on their company. The boys had already decided they needed to raise a round, and were attempting to make connections with Stein at DFJ.

At the first meeting, Stein peppered both Smith and Levie with questions about the company, business model and more. By 2AM the next morning, Stein received a multi-page response from the team with thoughtful, detailed response to each question. He saw this as a good sign. “There was an intelligence, an energy and drive in Aaron and Dylan that was immediately apparent. That’s not always the case in the valley,” he says.

And when evaluating whether to invest in the company, he thought that the product served a definite purpose in the business world, but had what he called “modest aspirations,” for Box. DFJ signed off on the investment and by July 2006, terms sheets were signed, and Box had raised $1.5 million from the firm.

From Consumer to Enterprise

What’s really remarkable about Box is that it began as a purely consumer-focused cloud-based file-sharing product before pivoting to become one of the most successful enterprise cloud services in the world.

Interestingly, it was Stein who helped define a set vision for the company in its early days. Box, at its start, was focused on both consumers and businesses, offering a dead simple way to store files. In 2006, the company continued to iterate on both sides of the business, launching file sharing options for consumers and businesses. But Stein, who was an active part of Box’s business (and served on the board), saw the writing on the wall that enterprise customers were “stickier,” in his words, and pushed the company to “sharpen its focus.”

The company began tailoring the product towards business users around 2007, and as Stein says, “engagement went through the roof.”

Another added feature which helped boost enterprise use was security, which was added in 2008. The company found that businesses were willing to pay even more for added security and permissioning. While not the sexiest product feature, the ability to have administrative control over data was really a turning point for product, says Stein. The addition of admin controls and security played into the needs of big companies, and CIOs started to actually pay attention to Box.

It was these offerings that caught the attention of Justin Slaten, Director, Information Technology for Wasserman Media in 2007. “There were lot of companies popping up at time that were consumer facing products in file storage but weren’t focused on the enterprise,” he says. “Box was the first company that was willing to offer a product that focused on business users.”

By 2008, the company still had just a handful of employees but Levie and Smith were both settling into their defined roles within the business, with Levie as CEO and Smith as CFO. As Stein explains, the founders’ strengths were complimentary from the beginning. “Aaron is focused more on the product, design and technology part of the business and Dylan is drawn to the economics and business model. These defined skill sets allowed them to focus on building business and think about it holistically.”

Not only did Smith and Levie workdays and nights together, but they were also roommates and actually lived at the offices until 2008. The company eventually moved to Palo Alto shortly after the DFJ funding round, and the Smith and Levie took a loft above the office, which had just a few mattresses on the floor.

Living and working together usually doesn’t work for most founders, especially when they are actually sharing a bedroom. But Smith explains that they developed systems early on to be able to live with each other, calling Levie more of a brother than a friend.

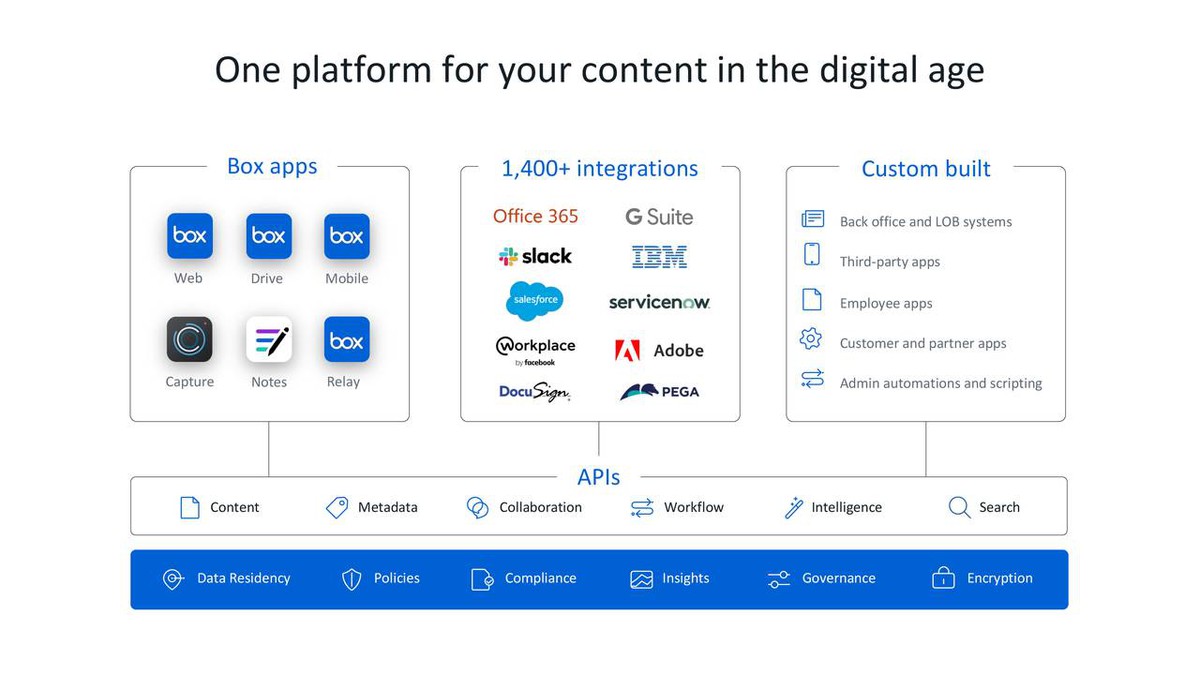

Becoming ‘Dropbox for the Enterprise’ & Going Public

As competitors started popping up in 2007 and 2008, Box focused on strengthening its enterprise product even further. Box steadily evolved into more than just a file storage platform, becoming a full-fledged collaborative application where businesses can actually communicate about document updates, sync files remotely, and even add features from Salesforce, Google Apps, NetSuite, Yammer, and others. Mobile is another area where Box has been focusing, adopting HTML5, launching iPhone, iPad, and Android apps and more.

Along the way, Box realized the market was much bigger than file storage. As it evolved into a collaboration platform, the company realized the enormous opportunity in providing a simple, cloud-based alternative to legacy systems like Microsoft SharePoint. The company began aggressively campaigning for existing SharePoint users to make the switch.

Stein says that in 2009, he realized that Box was going to be a multibillion company. “You could see acceleration of taking off. In 2010, the company doubled the amount of sales reps selling the product to businesses and sales and productivity skyrocketed.”

And then the acquisition offers started coming in. Turning down the acquisition was a very clarifying experience for both investors and Box’s founders because it set a clear goal for the company. The expectation was at the time was that if Box stayed independent, the company was going to really go for it, with the goal of eventually becoming a public company.

“I think you get these opportunities once every decade where such a massive change is happening in the landscape that enables a startup to be at the center,” says Levie. “And there is a lot of pressure to make sure you build something successful when making the decisions to stay independent.”

As for going public, Levie says that inevitably employees and investors will desire liquidity and being a public company afford this opportunity.

Stein echoes Levie’s thoughts, and believes the company is in a prime position to be a public company. “Enterprise SaaS companies are perfectly suited to be public companies. The company’s gross margins are north of 70 percent and there’s recurring revenue, which is great for the public markets,” he explains.

“I think Box is the kind of company we see once every decade at DFJ. I compare it to Salesforce but I think Box is actually creating an even larger category of enterprise software. I think it has the potential to be the next email; basically what company intranets are supposed to be,” he says.

Thinking Outside “the Box”

Box has certainly had more than its share of lucky breaks over the years, but the company’s growth trajectory and success have been anything but accidental. Box is one of the very few companies to make a radical pivot at a critical growth stage and succeed. It did so by thinking smartly about the limitations of its new target market and by solving universal problems better than anybody else.

Data storage and file management might not be the most interesting use cases in tech, but Box’s remarkable journey—and what lies in store for Levie and his company—is more exciting than most apps, consumer-focused or otherwise, could ever hope to be.